The (very) good news is that there is more than one zero-emission aviation technology coming. But at the risk of being Mr. Negative, at least for airport communities, electric airplanes are no panacea. And we say that not to inspire despair but to tell residents the realities, which are:

- Each of these alternatives comes with its own set of challenges.

- None of them are realistically happening in less than 25 years.

We cannot just accept the status quo as something we have to ‘wait out’ until “the aviation of the future” comes along.

Noise

The noise profile of large electric aircraft on landing will likely be quite similar to current jets–at least during arrivals. This is because the vast majority of aircraft noise on landing comes from friction on the airframe and not the engines.

Now, if you’re having trouble imagining this, just think about one of those sci-fi movies where a ginormous asteroid hits the earth. Ya know that loud whooshing sound effect? That’s real; even if the movie is fake. Any massive object (like an asteroid or a commercial aircraft) flying through the air at hundreds of miles an hour generates a tremendous amount of friction. That friction is the vast majority of the noise you hear when a plane flies overhead. (Even that ‘whistling’ sound, so many residents complain about? That’s a design issue unique to Airbus, which could be corrected today.)

And remember, most aircraft already pretty much coast the last several miles to the runway. As NextGeTheir engines are either on ‘low’ or even disengaged. But still, they’re coasting at hundreds of miles an hour. So the level of noise for landings would not significantly change with electric motors. That’s especially bad news for residents under the Third Runway 34L–which is now the airport’s preferred arrival runway.

Batteries are heavy

Unless there is a truly major breakthrough in the physics of energy storage, battery technology will likely only accommodate aircraft of perhaps seventy passengers by 2050. This comes down to weight. For an equivalent amount of energy storage, batteries are much heavier than Jet-A. That passenger count is significant.

Second Airport

If there is a second airport in the next 25 years it will likely be what is known as a green field site, which means “undeveloped land”, most likely far away from urban centers. That will limit its market desirability to regional flights which carry (how about that?) 70 seats. ICAO/FAA defines these smaller aircraft as “Air Taxis.” Until the Third Runway, air taxis and general aviation private planes comprised as much as 50% of operations at Sea-Tac Airport.

But today, about 97% of KSEA is commercial air: which means >70 seat and cargo flights. Commercial aviation needs big capacity, both for passengers, for belly cargo and for dedicated cargo flights. ‘Big’ is the entire economic model of the commercial aviation industry. That is why the Port of Seattle, and every regional planner has been trying to get SR-509 built for fifty years.

If/when the industry shifts to electric aviation, those planes will most likely service regional airports, the ones designed to handle smaller aircraft. Electric aircraft will not be able to lift the passengers and freight commercial carriers exist to service.

How can we be so sure about this? Because most ‘blue’ states will eventually phase out sales of fossil fuel powered cars and trucks. But what they will not do is attempt to place such limits on marine or aviation fuels. Even Jay Inslee, “the climate candidate for President” created carve outs for aviation and marine fuels in all his proposals, both as Governor of the State of Washington and as a candidate for President in 2020.

Paradigm Shift

So, if the commercial aviation industry really does shift to electric, it will not happen like automobile owners switching from a Ford to a Tesla (same roads, same amenities, different energy source.)

It will be more like the music business shifting from CDs to Spotify… with all those silly “download cards” in the middle.

There is no way to predict what an industry based on smaller aircraft might look like. (Does that mean twice as many smaller operations every day?) But one thing is for sure, the airline industry is not looking forward to it because every time there has been this big a shift? It has been ugly. How ugly? Although a few of the brand names remain, there are literally no survivors left from 1978. Does anyone remember Flying Tigers? Pan Am? TWA? Eastern? Anyone?

SAF and H2

The commercial carriers are therefore supporting a two-phase response to climate change: in the short term, Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), which is a canard since SAF itself requires massive amounts of clean energy to be synthesized from biomass. There is only so much clean energy. There is only so much biomass.

But that’s simply a stop gap move. In fact, their current commitments (ICAO/FAA) are only to get to ten percent (10%) adoption by 2029. Long game, their best bet is liquid hydrogen (H2). Liquid hydrogen is, like batteries, zero emission. Also like batteries, in practical deployments, it’s not as energy dense as Jet-A. But unlike batteries (which often weigh more than the chassis they are asked to move) H2 is lighter than air. So, H2 can be retrofitted onto the current commercial aviation system. In fact, this would be very similar to the world going from a highway full of gas-powered Fords to a highway full of Teslas. What’s not to like, right?

Well, there’s the same issue as with electric: the practical tech is decades away. But assuming we’re willing to wait, and assuming one can convince consumers that an aircraft filled with hydrogen is a better idea in 2037 than it was in 1937?

The people on the ground…

The public has come to accept (or at least not think about) having nine million gallons of Jet-A stored under Sea-Tac Airport on any given day. It remains to be seen how they will feel about having an even larger storage facility of even more flammable liquid hydrogen (kept at a constant and bracing -270°F) nearby. Losing a couple hundred people in an aircraft fire is horrifying. An H2 fire in an urban setting like Sea-Tac Airport may be unmanageable.

Move fast. Break things

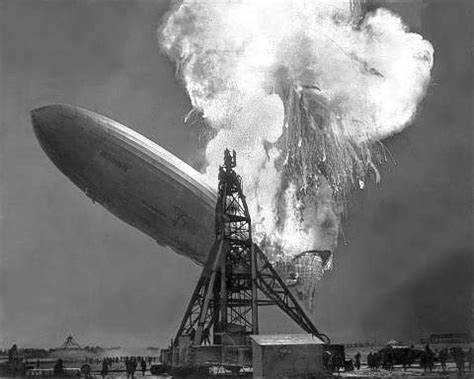

Perhaps you saw that image of the Hindenburg Disaster and found it to be a bit excessive. We disagree. What scares us about every aviation technology shift is that the public has under-reacted. Shifts in aviation tech have always had three features:

- New tech is always rushed into with open arms. From the first commercial jets to SSTs, both the allure of both general and commercial aviation, and the arguments about ‘progress!’ have been so powerful that there has been almost no consideration for people underneath the flight path. In the 1960’s, Boeing ‘bet the company’ on supersonic flight, knowing full well the noise profile. The entire industry, electeds, and regulators seem either blind-sided or indifferent to public reaction–even when it has been completely predictable.

- If decision makers were that gaga about a technology as terrible for residents as supersonic aircraft, why wouldn’t they underestimate the community risks of H2 storage today? In fact, every new aviation technology has had terrible and permanent consequences for the surrounding communities.

- None of these consequences has been accounted for in advance. Communities always have to react after the fact, even though those negative impacts are completely predictable.

And there is a new problem this time around, which we find truly insidious: the new technologies are being used to slow walk mitigation possibilities now. Like the arguments for a second airport, decision makers (like Governor Inslee) are on record saying to communities,

1“We know it’s bad. But aviation is simply too important to the region. That’s why we need to move as fast as we can to electrification. Hang in there. They’re coming. Sooner than you think.”

No, they are not. They are a quarter century off–and that’s if everything goes according to plan. As we’ve seen it’s not merely getting to seventy seat electric aircraft. It’s re-configuring an entire industry, including multi-modal connections, to match the very different capabilities of the new technologies.

Focus on now

There are things we can and must do to make life better for residents under the flight path now and it is unconscionable to use the future to avoid dealing with the present.

Because many of the concerns people have today (such as noise), they will still have with “the aviation of the future.” We just don’t know yet what they all are.

The shift to either electric and/or liquid hydrogen is coming. But not today. And perhaps not in your lifetime. But it is coming. Instead of waiting for “the aviation of the future” to save us, we should be implementing strategies to improve our communities. Now.

We must recognize that the allure of new technology is more than just seductive, it is, in itself, keeping us from obtaining justice.

We will leave advocacy of future technologies to others. They do not need us to fight their battles, which are, and will be those of the marketplace. Instead, we urge airport communities to see the shift in aviation as a unique opportunity. Instead of responding to that shift, we can become an essential part of that shift. We can get paid, now, regardless of who wins that battle, instead of hoping it will provide relief after it is rolled out.

Here is one thing you can take to the bank: any improvements we make to quality of life for residents under the flight path now will only benefit the future. The things we advocate for now, will be just as useful to airport communities in 2050, regardless of what powers the aviation of the future.

And here is another: Over the 100 years of commercial aviation, technology has always been focused on benefiting the people who fly, not the people it flies over.

We cannot count on technology to give us the communities we deserve. That is up to us.

1Association of Washington Cities annual meeting, January 2020.

Yes, so agree with you. If electric plans were do easy to do, seems the piston driven planes that still have lead in their fuel and increase the lead in the air and ground around airports would be the first to benefit.

The same can be said for jets that fly using biofuel. There is no decrease in the noise and no decrease in many of the toxic emissions. We need a systemic change in how we travel that does not destroy neighborhoods.