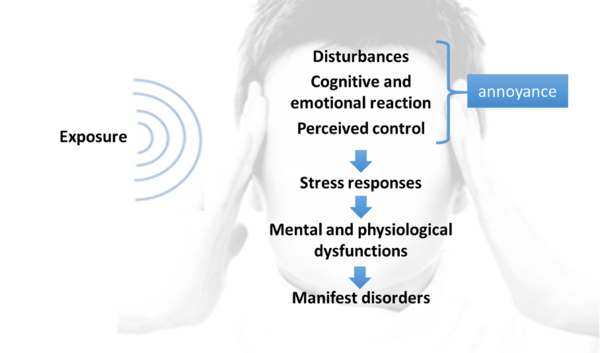

Annoyance, is the term of art describing a level of unwanted and/or harmful sound that is not damaging to hearing. That is how it was first used in research literature. We think it’s time to come up with a new term because ‘annoyance’ is dismissive of the impacts that aviation noise has on public health. And public health is how we now need to think about noise.

For a very long time, researchers understood that chronic noise exposure could have detrimental effects (particularly for childhood learning). But it was not until the 1970s–and in large part because of the Sea-Tac Communities Plan of 1976–that the FAA started taking the community impacts of aviation noise seriously.

In 1979, Congress passed The Aviation Safety and Noise Abatement Act (ASNA), the first of several laws establishing Noise Exposure Maps, Sound Insulation, the whole shebang now known as Part 150.

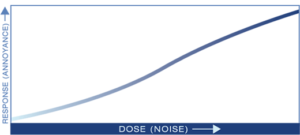

ASNA also established the use of a very medical sounding methodology to evaluate people’s reactions to noise called dose-response. In this case, the dose is the noise and the response is the percentage of people considered ‘highly annoyed’. Now if ‘annoyance’ sounds more like psychology than physiology you’re not wrong. We’ll get to that.

ASNA also established the use of a very medical sounding methodology to evaluate people’s reactions to noise called dose-response. In this case, the dose is the noise and the response is the percentage of people considered ‘highly annoyed’. Now if ‘annoyance’ sounds more like psychology than physiology you’re not wrong. We’ll get to that.

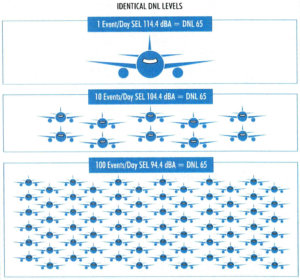

The noise is measured via DNL, a complicated unit of measurement that sounds like a ‘decibel’ but is not really. It’s more like an average meant to factor in several other factors including the type of aircraft and the time of day (night time flights being disruptive of sleep.) But to give you a sense of how complicated it can get, one extremely loud overflight at 2:30am in a 24 hour period could mark your home as DNL65. Or ten flights. Or 100 flights. Or several hundred. It just depends.

The noise is measured via DNL, a complicated unit of measurement that sounds like a ‘decibel’ but is not really. It’s more like an average meant to factor in several other factors including the type of aircraft and the time of day (night time flights being disruptive of sleep.) But to give you a sense of how complicated it can get, one extremely loud overflight at 2:30am in a 24 hour period could mark your home as DNL65. Or ten flights. Or 100 flights. Or several hundred. It just depends.

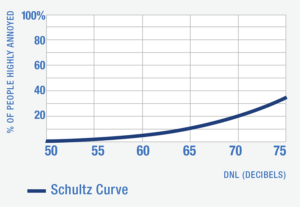

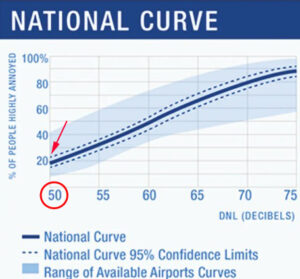

Whether or not you agree with that methodology, this research was summarized by the Schultz Curve. As you can see, 20% of the public were found to be ‘highly annoyed’ at that DNL65. The ‘dose’ (DNL65), at a ‘response’ rate of 20%, became the dividing line between homes that are eligible for sound insulation grants and those that are not.

Whether or not you agree with that methodology, this research was summarized by the Schultz Curve. As you can see, 20% of the public were found to be ‘highly annoyed’ at that DNL65. The ‘dose’ (DNL65), at a ‘response’ rate of 20%, became the dividing line between homes that are eligible for sound insulation grants and those that are not.

Annoyance vs. Health

Important: there is nothing in Part 150 addressing health impacts. It is 100% focused on annoyance, which is, again, a matter of opinion.That approach may have been more understandable in 1979 when research into the physiological impacts of aviation noise were still in their infancy. But forty years on, in addition to learning problems for children, the impacts to sleep, stress, hypertension, diabetes and other cardiovascular diseases from aviation are better understood. And they are profound.

(One problem is that most previous research had been done on traffic, which is a more continuous sound, than airplanes which are isolated events. It turns out that physiologically, humans respond far differently to each type of annoyance.)

Hush Money

DNL65 and 20% may seem arbitrary choices for establishing who gets sound insulation and who does not. But as a practical matter that was partly because that was the amount of sound insulation FAA was able to pay for.

This is important: the FAA only gets a certain amount of total funding every five years from Congress in the FAA Reauthorization Act. Back in 1979, somewhere, someone at the FAA, set that initial DNL65 to balance the amount of money available for sound insulation with other priorities such as safety, construction projects, etc.

Local context: The FAA gave the Port of Seattle $300,000,000 in grants to provide roughly 9,400 Port Packages around Sea-Tac Airport.

Sound insulation is usually considered the least efficient form of noise mitigation. Generally, it is far less expensive to attempt to reduce the source of the noise. So in addition to providing funds for sound insulation, the FAA also has heavily funded voluntary industry efforts to develop quieter aircraft. To a certain extent the industry has succeeded. Newer aircraft really are quieter.

However, there is only so much that can be done to reduce the noise profile of any 400,000 lb. object flying overhead at 250mph. One can make an aircraft measurably ‘quieter’ on takeoff, but barely move the needle as to the annoyance for people under the flight path. Why? Most of those improvements are engine-related. It turns out that as much as 90% of the noise, except during takeoff, comes from the airframe alone.

Thus, the FAA has completely exaggerated those improvements for the community.

How exaggerated? The FAA would claim that today only 400,000 people in the entire United States are now heavily impacted by aviation noise.

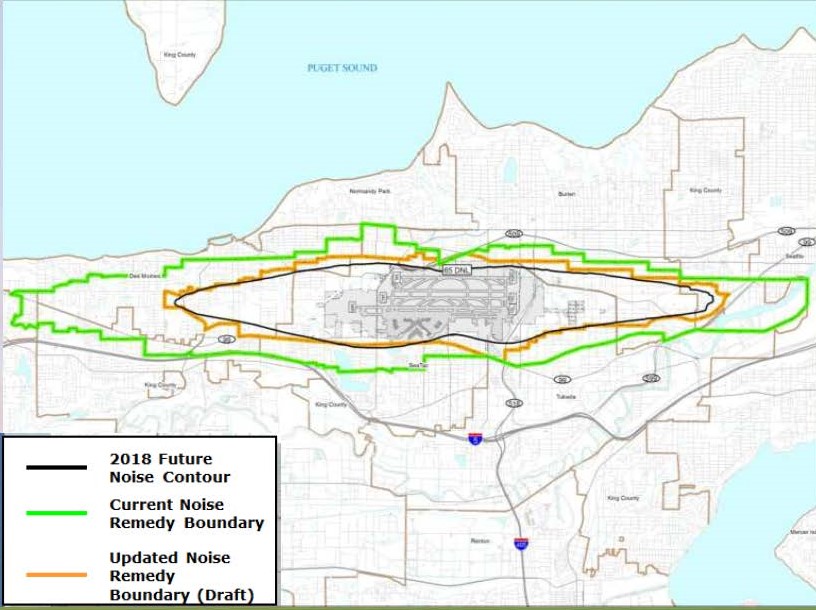

Local context: The FAA would say that, of the 67,000 residents who were heavily impacted by aviation noise in 1991, only 9,700 are as impacted today– due to newer, quieter airplanes. An 85% improvement!

Which is ridiculous. But also happens to almost match the claimed reduction in noise of modern airplanes like the 787. What a coincidence.

A new survey, a new curve

But the FAA has continued to work the issue from the community point of view. In 2021, they conducted a Neighborhood Environmental Survey of 10,000 residents at the 20 largest airports–the first since 1979. The Technical Analysis resulted in a new curve; the National Curve.

But the FAA has continued to work the issue from the community point of view. In 2021, they conducted a Neighborhood Environmental Survey of 10,000 residents at the 20 largest airports–the first since 1979. The Technical Analysis resulted in a new curve; the National Curve.

- On the plus side, the National Curve now confirms what European and United Nations researchers have been saying for years: the percentage of highly annoyed people living under the flight path is three times 1higher.

- On the other hand, as we just saw, the regulation governing sound insulation funding still only applies to the DNL65, and thus only one third the homes.

Public Health vs. Personal Preference

Our view is that whether people find airplanes ‘annoying’ is irrelevant and we challenge the entire survey. Rather than move the discussion from sociology to public health they fell back on the forty year old concept of annoyance, which is, again, highly personal–and notably, not subject to regulation.

Many people will honestly respond to a noise survey saying they enjoy the sound of commercial aircraft–even though chronic exposure to noise is bad for learning outcomes and cardiovascular health, especially for the elderly. Health impacts have nothing to do with annoyance.

So despite all the trappings of public health (eg. dose-response), annoyance is a matter of opinion and thus not subject to regulatory authority.

And that is why the FAA and the industry want to engage the issue in those terms. It’s a distraction.

No matter how annoying we find the noise, at some point, we must stop fighting ‘Annoyance’. It is the subjective nature of annoyance which makes it impossible to move to regulatory authority.

It is unacceptable that the FAA has responded to the DNL65 with yet another meaningless survey, but it’s even worse if we continue playing their game–which has no possibility of improving our situation.

Ultimately, this issue will be addressed much like secondhand smoke and drunk driving–an issue of public health rather than personal preference.

Today, no one says, “Don’t like my smoking? Move!” At a certain point, we win by making clear that this is a matter of public health, not a question of annoyance.

There is always someone else to blame

The original DNL65 boundary, which provided 9,400 Port Packages, today would only cover a third of those homes given the current DNL65—-because ‘the airplanes are so much quieter!’ But using the new NES, the number of homes eligible for sound insulation would triple.

The original DNL65 boundary, which provided 9,400 Port Packages, today would only cover a third of those homes given the current DNL65—-because ‘the airplanes are so much quieter!’ But using the new NES, the number of homes eligible for sound insulation would triple.

The difference? The DNL65 is what Congress will fund. The NES they will not. There is always someone else to blame.

Now what?

Congress

Washington State has some of the most powerful Federal electeds in commercial aviation. Senator Maria Cantwell is Chair of the committee responsible for the FAA. Representative Rick Larsen is ranking member of the House Transportation Committee. Neither put forward no amendments to fund more sound insulation or other meaningful mitigations in the 2024 FAA Reauthorization bill. To be fair, it is doubtful that there is more than a quarter of the membership of either body willing to vote for such funding. But given their influence, we think they should at least try. The next FAA Reauthorization is not until 2028, but all your electeds are up for re-election before then.

The Port of Seattle

There is also the Port of Seattle. There is nothing in Part 150 that prevents the airport itself from spending its own money on mitigations like sound insulation.

And the Port of Seattle continues to break records, and thus can write a check every second Tuesday of the month.

1The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has undertaken a multi-year research effort to quantify the impacts of aircraft noise exposure on communities around commercial service airports in the United States (US). The goal of this research effort was to develop an updated and nationally representative civil aircraft dose-response curve, quantifying the relationship between aircraft noise exposure and community annoyance. To characterize this relationship, the research team designed and conducted the Neighborhood Environmental Survey (NES), which collected information from a statistically representative number of adult residents living around a balanced sample of 20 US. Airports — objectively chosen to reflect the nation as a whole. From the survey data, a national dose-response curve was derived that describes the relationship between aircraft noise exposure [in terms of DayNight Average Sound Level (DNL)] and the percentage of individuals reported as being highly annoyed by aircraft noise. Aircraft noise exposure levels were modeled using the FAA Integrated Noise Model (INM), version 7.0d; based on 12-month sets of aircraft flight tracking data collected between 2012 and 2014 for each NES airport. Community response data was collected through a mail survey questionnaire, designed to follow the recommendations of the International Commission on the Biological Effects of Noise (ICBEN) (Fields et al. 2001), requesting respondents to rank on a scale from 1 to 5 (with 5 being most): “Thinking about the last 12 months or so, when you are here at home, how much does [noise from aircraft] bother, disturb or annoy you?” Responses of either 4 or 5 where then considered as “highly annoyed.” Just over 10,000 people completed and returned the mail questionnaire (resulting in a response rate of 40 percent); administered in six separate “waves” over a 12-month period beginning in October 2015. Logistic regression analysis of the “highly-annoyed” responses from the mail questionnaire and their associated aircraft noise exposure levels were used to generate the national doseresponse curve. The percentage of those surveyed who were highly annoyed by aircraft noise increased monotonically with increasing noise exposure. In comparison to prior studies on this topic, the NES’s national curve shows substantially more people highly annoyed for a given DNL aircraft noise exposure level.