As the name implies, The Sustainable Airport Master Plan, is a timeline for insuring that Sea-Tac Airport can continue to grow to accommodate passenger and cargo traffic over the next twenty years. (The FAA requires all large airports to have a master plan.) In its broadest sense, it is divided in two phases: Near Term Projects (NTP) and Long Term Projects (LTP). The Long Term phase is still pretty vague, but the Near Term phase is quite far along in design and covers from now through 2027. The Near Term is what this essay discusses. So when we refer to ‘The SAMP’ just assume we’re really talking about ‘The SAMP: Near Term Projects’.

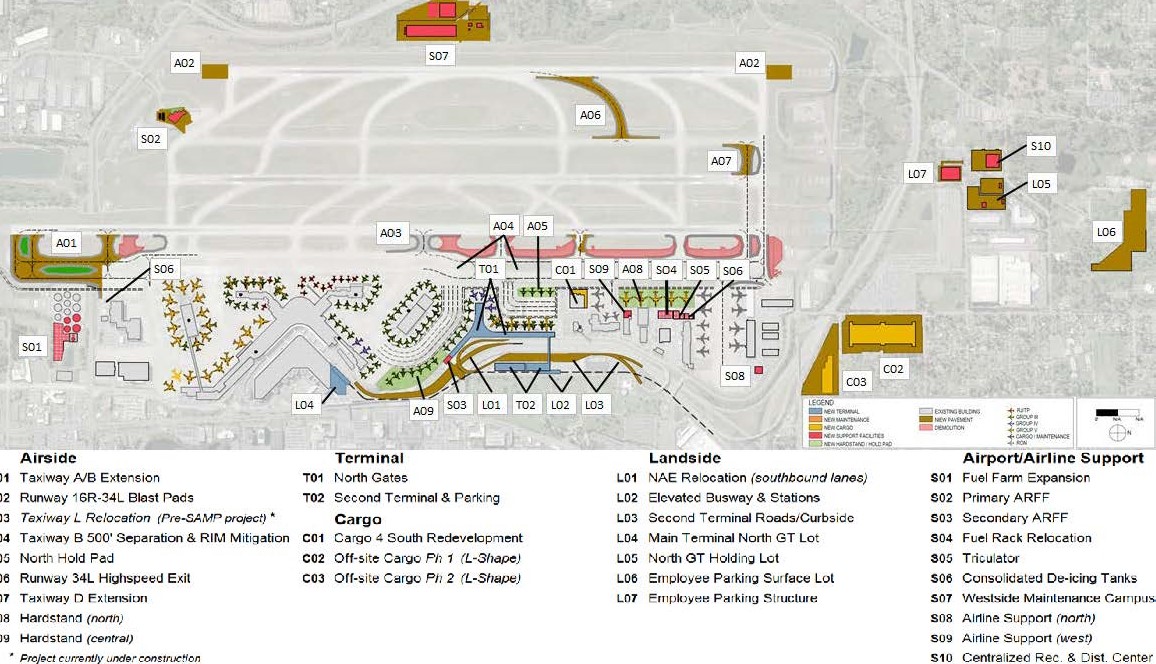

In practical terms: the SAMP is a series of about thirty construction projects with the goal of expanding capacity at Sea-Tac Airport, adding over 100,000 flights per year and tripling the cargo capacity of Sea-Tac Airport. It is occurring now and if done to schedule will be completed by 2027.

It’s different

The SAMP is very different from other airport expansion plans in several ways. In fact it’s so different that you (and local governments) might not even be aware that it’s happening.

One way SAMP is different from previous expansions is that it is not one big construction project (like the Third Runway). Instead, it is about thirty smaller, individual projects such as building nineteen more gates.

The second difference is that this expansion is possible because the airport no longer requires more physical space in order to dramatically increase operations. The SAMP is adding as many new operations as adding a physical runway would have done in the past. But it will accomplish that expansion inside the current property.

This requires a bit of an explanation.

GPS

Imagine you’re inside a control tower watching air traffic controllers. Our guess is that you probably see a dimly lit room illuminated by big round screens which represent little blips on a screen from RADAR antennas like this. That hasn’t been reality for a long time now.

Imagine you’re inside a control tower watching air traffic controllers. Our guess is that you probably see a dimly lit room illuminated by big round screens which represent little blips on a screen from RADAR antennas like this. That hasn’t been reality for a long time now.

When we say ‘GPS’ we’re already inviting howls of ‘over-simplification’. The FAA has a galaxy of acronyms to describe the technologies they use (like ‘Performance Based Navigation‘, aka ‘PBN’) and not one of them includes ‘GPS’. But at bottom, the whole system works a lot like GPS for your car so that’s what we’re sticking with. One term you may have heard is NextGen which is an umbrella for a slew of programs designed to optimize navigation–often to the detriment of surrounding communities. That discussion is far beyond the scope of this essay but you can read more about it in NextGen For Dummies.

Today’s aircraft are guided by GPS, not RADAR. Yes, just like your car’s navigation system. And the reason that matters is because RADAR is a very imprecise technology. Using RADAR, it was necessary to keep planes separated by several minutes (for this discussion it’s better to think of distance in terms of ‘time’ rather than miles.) You’ve probably noticed that aircraft take off and land much more frequently now and that’s because the increased accuracy using GPS allows flights to be spaced much closer. How much closer? Well, planes now the distances between airplanes can be measured in seconds. And with GPS you can safely take off and land on two parallel runways–which was never allowed with RADAR.

Today’s aircraft are guided by GPS, not RADAR. Yes, just like your car’s navigation system. And the reason that matters is because RADAR is a very imprecise technology. Using RADAR, it was necessary to keep planes separated by several minutes (for this discussion it’s better to think of distance in terms of ‘time’ rather than miles.) You’ve probably noticed that aircraft take off and land much more frequently now and that’s because the increased accuracy using GPS allows flights to be spaced much closer. How much closer? Well, planes now the distances between airplanes can be measured in seconds. And with GPS you can safely take off and land on two parallel runways–which was never allowed with RADAR.

The shift from RADAR to GPS has allowed for such a large increase in capacity that Sea-Tac Airport airspace can continue to accommodate the expected increases in operations well into the 2040’s without building another runway!

The problem is down, not up

OK, there is one little problem. GPS makes it possible to more efficiently share the airspace (fly planes much closer together). But what do you do with all the extra planes that are on the ground? Because if you take-off and land planes faster and faster, you have to have more places for them to park. You need more taxiways and gates and faster baggage handling and shorter security lines to get passengers on and off faster. And that is what SAMP is–a way to process more people and planes on the ground. Because the real limit on take-offs and landings is on the airfield, not in the airspace.

However what you don’t need to expand ground capacity are huge construction projects that make the surrounding communities concerned. Since all of it is inside the Sea-Tac Airport property, people in the surrounding communities don’t even notice. So one brilliant part of the SAMP (at least from the Port Of Seattle’s point of view) is that it has not generated anything like the opposition of previous expansion projects. And as proof, I submit the fact that the majority of the airport communities have no idea it’s even happening.

Now what makes things even worse is that local governments have also not reacted with much vigor. And as proof of that we offer the fact that the Port Of Seattle first notified the surrounding cities in 2012 that it would be doing some form of expansion (now known as the SAMP.) And everyone went to sleep.

It wasn’t until around 2017 that a very few local electeds and activists like Quiet Skies began screaming. And it was certainly not until 2018 that any of the City governments began to even raise serious concerns. (Why there has been so little interest from local governments is discussed in our article The Problem With Cities.)

NEPA/SEPA: The Dance

There are parallel Federal and State environmental policies created in the early 1970’s: National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA). The two kinda look the same and work the same within their respective governments. They’re not the same, however for this discussion, we’re gonna way over-simplify here and focus on NEPA.

NEPA has a review process that all construction projects need to go through. The builder needs to pass the review in order to proceed. And impacted communities like SeaTac, Des Moines, Tukwila, Burien, Normandy Park and Federal Way each assign a SEPA and NEPA representative (one of their staff and/or an outside consultant) to look at the project and provide comments as to their concerns.

These reviews are no joke because these agencies do have the power to severely hinder or even prevent such projects. In reality this rarely happens because people who invest that kind of money to build projects which require review also hire professionals to make sure that their projects will pass muster.

Now, what usually happens is that, after the review, the builder may be required to make some adjustments to the project, either to reduce the environmental impacts or to mitigate them.

Reducing the impacts might be if a factory were required to change some of its manufacturing processes to pollute less in the first place. An example of mitigation might be to put filters on the smokestacks or offer compensation to the affected community. This distinction matters.

The whole review process tends to be reactive. You wait for the builder to propose stuff and then the impacted communities provide comments and then the EPA or State Department Of Ecology respond–just like any building permit process. The problem is that in this process the builder continues to design (and even in some cases to actually build) during this review process. This ‘dance’ is so complicated we can’t go into it here. The only thing to understand is that the builder does not necessarily put everything on hold until they get approval from the controlling agency. It’s an ongoing negotiation.

EA or EIS?

Let’s back up for a second. At the very beginning of the process is the most fundamental decision of all: EA or EIS? You see, there are two possible levels of review for any building project: Environmental Assessment (EA) or Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). The EA is what the builder wants because it requires far less scrutiny and therefore offers much lower levels of risk and much lower possibilities for mitigation. This is granted if, from the outset, the project looks low risk.

An EIS is granted if the project looks dicier; if the project might have serious consequences for the community and thus requires much more scrutiny. The developer definitely does not want an EIS because all that extra scrutiny on the front end and all the possibilities for mitigation on the back end mean more costs. (Occasionally you’ll hear people refer to an EA as ‘EIS-Lite’.)

So: EA or EIS, who decides? Well, if this were any other type of factory? The EPA. (As we’ve discussed many times, an airport is a factory. The products are passengers and cargo and the smokestack is the cumulative emissions from all the aircraft.) But because of a change in Federal law passed in 1990, the authority for environmental review on airport projects now rests with the FAA. And unfortunately (and I’m not being political here, this is exactly what the law says) the FAA’s primary concerns are safety and efficiency, meaning safety of the airplanes and efficiency for the airlines. Community impacts matter, but they are not at the same level of importance as the interests of passengers and airlines.

In practical terms, what this means is that there is never a case where an airline is asked to reduce flights or an aircraft maker is compelled to build a less-polluting or quieter aircraft. (Aircraft pollute about as much today as they did in 1980.) If there is any harm reduction to be done at an airport it almost always happens with mitigation.

Thus far, ‘mitigation’ has mostly meant attempts to create sound insulation for homes or around airports. That’s it. Not really much to control the pollution. And the pollution is significant. Right now, Sea-Tac Airport is the single biggest polluter in King County and the second biggest in the entire State Of Washington. So anything that makes for more pollution means the worst polluter just becomes worser.

But the EIS is what you really want

Now let’s say that the FAA that only an EA is required. The builder moves forward, but very soon, all parties realize that they’ve underestimated the environmental challenges. Do they acknowledge the mistake and switch to an EIS? Theoretically, yes. But here on planet earth, that literally never happens. It seems that once that decision point has passed it is never re-visited–even when it is obvious that a mistake has been made. And there is also no legal precedent for any community successfully fighting to make that happen. So, in short, if the FAA rules that an EA is what is needed, your community gets a lower level of inspection and a lower set of possible mitigations and that’s that. Read that again: If the builder is only required to go through an EA review, it permanently curbs the possibilities for mitigation; even if evidence appears later in the building process that makes new impacts obvious to everyone.

Getting an EIS is challenging

OK, so we need an EIS, not an EA right? Well, here are some challenges. The first and largest can be stated in two words: individual and cumulative.

See in addition to being something of a stealth expansion (no one outside the airfield even notices what is going on), remember that the SAMP is not one ginormous project (like the Third Runway.) It’s thirty smaller individual projects. By themselves, none of the individual projects can be argued as being ‘significant’ in terms of pollution.

And this is the loophole in the law you could fly a 747 through. The current law says that the decision maker can judge the ‘impact significance’ of these small projects individually, ie. based on the impacts that each project makes by itself. There is no requirement to consider the total impacts of all thirty projects cumulatively, even though there is no point in doing any of the individual projects à la carte. They really are a complete system (which is why it’s called The SAMP, right?) But that’s how the law works. And that’s the difference between individual and cumulative. The community needs for these projects to be evaluated cumulatively in order to have any chance at fair and reasonable mitigation.

Ladies and Gentlemen, we’re in a holding pattern…

The current situation is that we are waiting for the Port Of Seattle to finalize its design for most of these projects. And at each point, the State and FAA are waiting to judge several things: Do we get an EA or an EIS? Do we judge the projects cumulatively or individually?

Now one other thing, which concerns the boring subject of project management. The progress of public projects are periodically reviewed to make certain they are on track. And this progress is measured in terms of percentage completed (as of July 2020 we’re at eight percent.) So at each decision point, the Port Commission votes to either move ahead or take a step back. When the project reaches thirty percent (30%), they’re all in. All the contracts with developers, unions, etc. are now full speed ahead. And that’s the counter everyone watches. Because it’s at that point that the decision point on EA and EIS comes to a head.

Reactive or Proactive?

As we noted earlier, this whole review process tends to be reactive–communities wait to see how the FAA reacts to the designing and building before deciding what to do. But it doesn’t have to be that way. The Cities could take legal action with the goal of compelling the FAA and State to decide on an EIS now. And we could also ask a court to judge that this project must be evaluated based on the cumulative impacts to the community of all thirty projects; not on each project individually. It’s also important to note that our region has some very gifted legislators at the State and Federal level. And they can also help on this issue. A discussion of all those possible responses can be found here.

The SAMP is not the whole enchilada

Before closing, it’s important to note that the SAMP does not have to be the focus of all airport discussions. However, it’s important to recognise that there is a strong gravitational force which tends to make it so. It is to the Port’s advantage to try to focus all discussion on the SAMP, which you’ll hear when any concern is raised, “We’ll deal with issue ‘x’ in the SAMP.” And as noted, many of the Cities have not been particularly engaged on airport issues so some may be easily persuaded to this argument since it is the path of least resistance. However, again, this is a reactive approach and as we’ve said many times, that it is likely not the most effective approach in achieving long term reductions in noise and pollution.

I, as well as most of my friends & neighbors living within the Woodmont Country Club & surrounding countryside are all highly negatively impacted (no pun intended) on a daily round-the-clock 24-7 basis! I & many others are extremely interested in reducing any & all the related toxic environmental consequences! Please keep me informed!