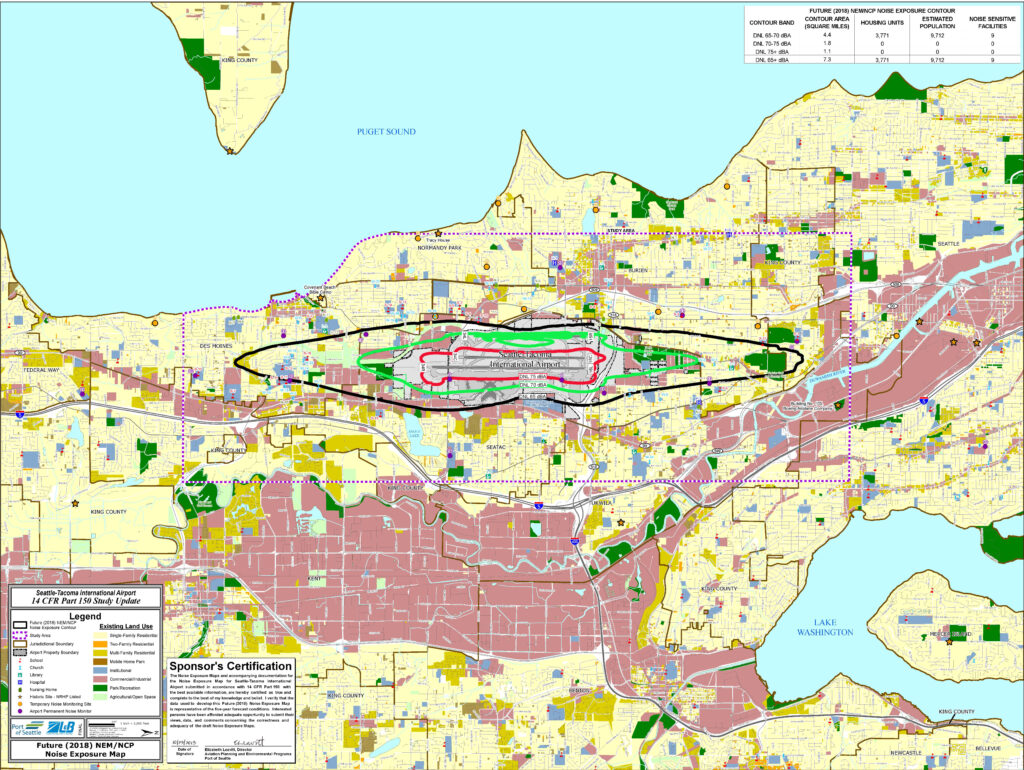

There is a geographic area around every large airport where, according to a formula developed by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the ‘noise’ level is equal to or greater than 65 decibels DNL (Day Night Level). That area is depicted on a noise exposure map (NEM) and referred to as the Noise Boundary or just ‘DNL65’. This map is developed through a years-long process called a Part 150 Study.

Now DNL65 isn’t something you can measure. There is no microphone that measures sound in ‘DNL units’. So talking about ‘decibels’ is misleading. It’s actually a formula that attempts to combine all the flights someone might experience over their head every day and night into one number representing ‘annoyance’. Among the many unfortunate aspects of the formula is the fact that saying ‘decibels’ creates the entirely false impression that it is a measurement. The Noise Boundary is not determined by measurements.

First off, the formula gives special weight to flights at night as being more annoying than those during the day. That makes sense. But on the other hand, it also allows for individual flights (referred to as a SEL) to be much louder than 65db. Again, ’65’ doesn’t represent any measurable unit per sé. You just have to assume that if the number over your house is determined to be ’71’, that means your experience is somehow more ‘annoying’ than it would be to an average guy down two blocks where the number is calculated to be ’57’.

As with all things government, the whole point of DNL65 was money. If you’re inside that boundary (because the spot you live in is calculated as ’71’ using the formula), your home may be eligible for noise insulation money from the FAA. FAA grants are how Port Packages at Sea-Tac were funded. Everyone inside the DNL65 boundary (with a number 65 or higher) got sound insulation. Those outside (with lower numbers), were left, well… outside.

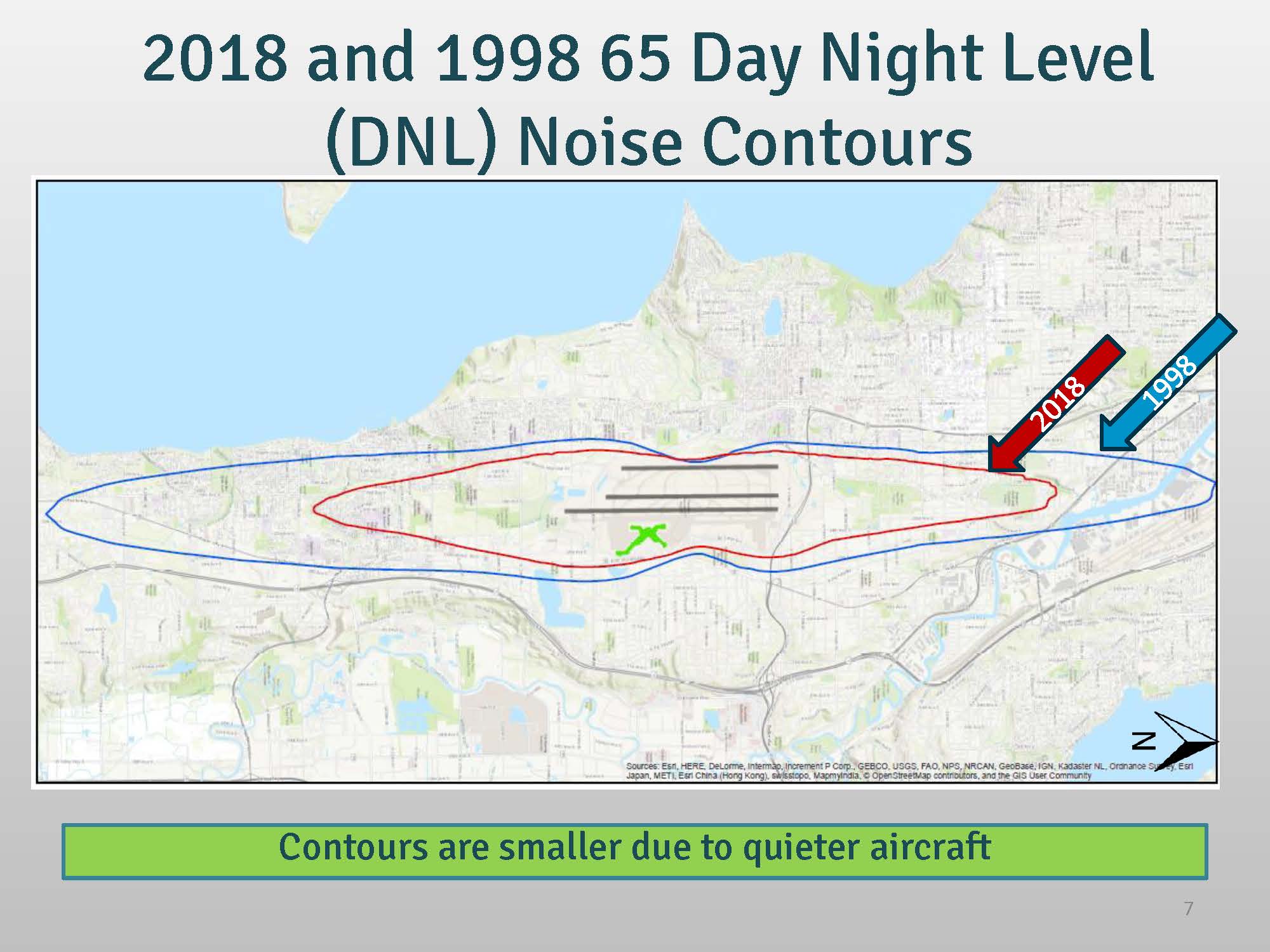

Now according to the FAA, the size of that boundary keeps decreasing every year because:

- Newer aircraft keep getting quieter and

- The flight paths keep getting tighter due to NextGen

Both things are true. And in fact, the FAA will tell you that the ‘average’ annoyance has actually decreased by almost 2/3rds in the past 30 years. Hooray for technology.

OK, so why does that feel like a cruel joke if you live near an airport?

Some technical reasons why DNL65 sucks…

- The formula is calculated, and not based on measurements. In other words: 1no one goes out with a sound meter and actually tests the noise levels around the airport. They look in text books that have a particular number for each aircraft type, engine and a bunch of cockamamie stuff involving topology, geography and wind patterns. It’s 100% contrived and often wildly inaccurate compared to sampling.

- Newer models of aircraft are getting (somewhat) quieter. The calculation is based on the overall mix of aircraft departing and arriving over time across the entire air space. But of course ‘quieter’ is a relative term. Every commercial jet will always make a lot of noise. And (fun fact) it is estimated that 90% of the noise of a commercial aircraft flying over your head comes from the air frame and not from the engines. So even the noiseless electric engine of the future would not be a significant improvement.

- The formula does not take into account frequency when it comes to annoyance. When a human encounters 700 flights a day—even if they are ‘quieter’ than in past years, the cumulative effect on the body is much worse than, for example, 100 ‘noisier’ flights from 30 years ago. The formula assumes that we are all less ‘annoyed’ now because the ‘average’ aircraft is marginally quieter. But it completely ignores the massive increase in quantity of exposure.

- The number ’65’ was always way too high. It was set that high many years ago because, frankly, it was impossible to sound insulate homes to anything much better at the time at what was considered to be a reasonable cost. Research on human health now makes it clear that the number should probably be less than 45. Everyone (including the Port of Seattle) would agree with that. And today, just as there are techniques to make aircraft (somewhat) quieter, there are also ways to sound insulate homes much more effectively. Again, the number ’65’ was largely based on money.

Now the bad news: physiology

It is remarkable what human beings can become acclimated to.

When a human being hears a loud noise, it creates a state of physical arousal. It’s a survival mechanism. It’s automatic. And affects you even if you absolutely love jet airplanes and have heard them fly over your head 100,000 times. Many people living near airports get so used to it they may not even notice it consciously.

But again that physical response occurs every time to some degree. The blood pressure elevates, stress hormones are generated. Whether you notice it or not, when you get into that state of excitement it takes a few minutes to return to normal.

When flights are spaced more than a few minutes apart, the body has at least some rest period to return to normal. But when they are coming almost continuously, the body never has a chance to calm down. It creates an almost constant low-level state of arousal at a physical level and over time this seems to have, what scientists refer to as a ‘weathering effect’. It basically wears the body out prematurely from a constant low level of stress. Again, many people get so used to it that they are not even consciously aware that it’s going on.

Conversely, even one or two flights at night can have the same arousal effect. When we’re asleep, many of us are deeply affected when a flight goes overhead. And sleep is such an essential function that, even if it happens every night, our bodies never become acclimated–it keeps making us jump every night at 3:05AM.

The tricky part has been in getting the government to recognize that noise is a serious health issue. For example, the term of art the government uses to describe the effects of noise is ‘annoyance’. It’s not mere semantics to say that the term itself discounts the importance of the issue. Calling these health effects ‘annoying’ automatically creates the impression in decision-makers minds that the sufferers are simply ‘complaining’ and that the problem is not serious enough to warrant action.

Oh, you think we’ve been dodging the question?

Astute readers will note that we’re now at word 900 but have almost completely avoided explaining how ‘DNL65’ is calculated. That was intentional because in our view, the whole program is emblematic of what the public imagines when they think of a bad government program. It is, crazy expensive, super-complicated, appears to be in the public interest, but has in fact, turned out to be just the opposite. It is, by design, meant to avoid compensating people living near airports.

But this avoidance may have led you to believe that we (perish the thought) are just making it up, Fine.

If you really care about how those boundaries are worked out, or even want to delve into what the DNL65 actually means, start here.

If, after studying the Part 150/AEDT system, you find that it makes perfect sense? We definitely want to hire you.

1OK., that’s not 100% accurate. A small number of measurements are taken, but only as inputs to a computer modeling program, not ongoing sampling. In other words, if your home is within the DNL65 boundary that is not because someone took measurements which somehow ‘prove’ that some ‘average measurements’ were below 65dBA.