An ambitious plan to bring bullet trains to the Pacific Northwest has drawn champions including former Washington Gov. Christine Gregoire and Microsoft President Brad Smith. They argue high-speed rail could interconnect the growing regions around Seattle, Portland and Vancouver, B.C., like no other form of transportation can.

They bring a compelling vision but with it a daunting challenge. “Ultra” high-speed rail, estimated to cost up to $150 billion, would need new track and trains that travel at 250 mph — among the fastest in the world.

But if advocates are ever able to ignite the enthusiasm necessary for a high-speed corridor, the region must first demonstrate it can operate the reliable rail service it already has.

And on that goal, we are far off-track.

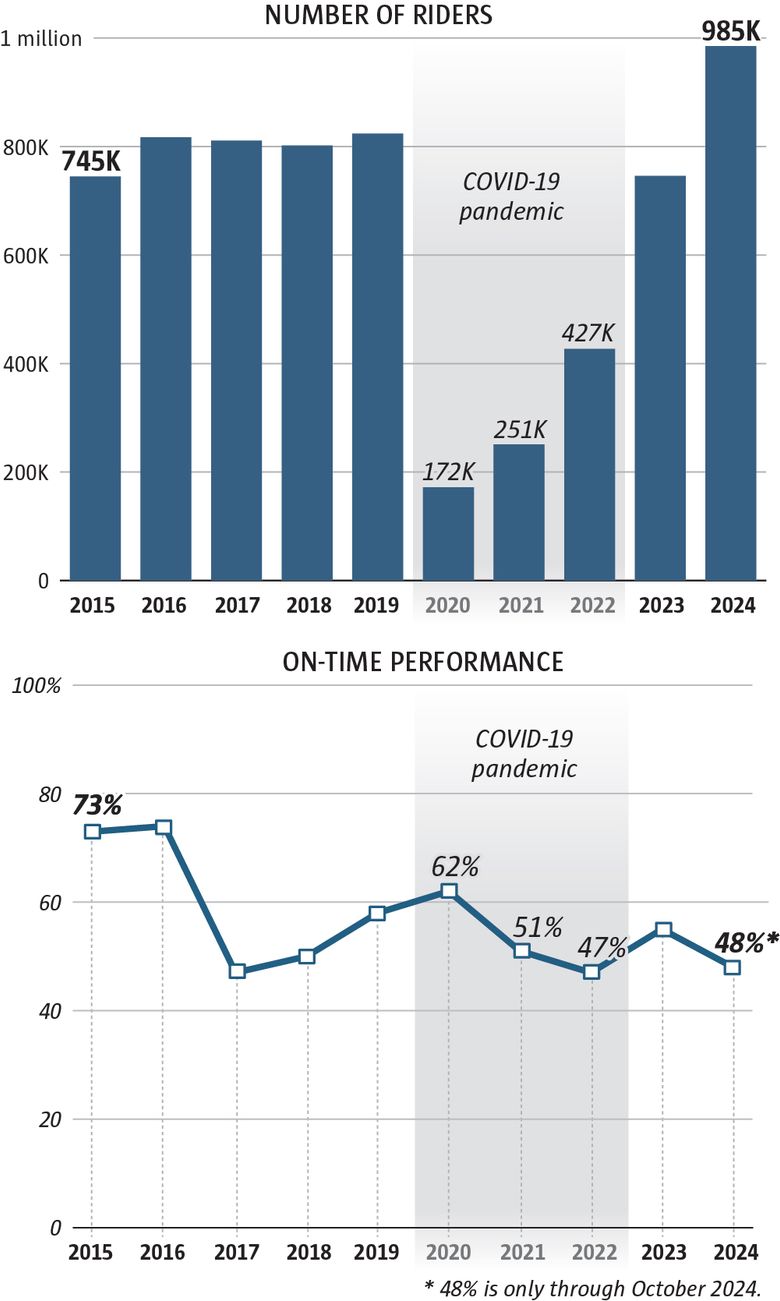

Intercity rail service is unacceptably slow and undependable. Today, Seattle passengers boarding an Amtrak Cascades train for Portland face a three-hour, 30-minute journey; the voyage north to Vancouver B.C., takes a solid four hours. Worse yet, the trains are late half the time.

It’s high time to make infrastructure improvements to an intercity service that can grow its ridership and build support for the Northwest rail travel of tomorrow. But those improvements also serve their own future role as complementary to a high-speed rail line.

Gregoire, as a leader of the Challenge Seattle group helping to secure funding, puts it this way: A planned 50-minute bullet train to the three big cities of the Northwest will make limited stops, if any. Passengers will still need an intercity train to get to smaller destinations along the way.

“I don’t think it’s one over the other,” she said of the two kinds of rail.

Missed opportunity

Intercity rail advocates like consultant Thomas White, a former Burlington Northern train dispatcher and planner, criticize the state’s transportation department, which manages Amtrak Cascades. They say it has missed opportunities to improve intercity rail, because high-speed rail planning has become a higher priority for the agency.

White points to the Obama administration, when nearly $800 million in federal stimulus funds ultimately built a track bypass around a congested freight tunnel near Tacoma, upgraded signaling and track siding, and more. The missed opportunity, he says, was another federal spigot of billions of dollars — the infrastructure and inflation reduction acts passed under President Joe Biden — and too few shovel-ready infrastructure projects pursued for Amtrak Cascades service.

It wasn’t a swing and a miss. Rather, it was a failure to show up at the plate, echoed Tom Lang, program manager for the nonprofit Pacific NorthWest Economic Region, which advocates for increased ties between local provinces and states.

“We had a big opportunity to invest in infrastructure between the cities and improve the rail connections and we did not do that,” Lang said in a January presentation to the Washington State Transportation Commission.

Jason Biggs, WSDOT’s Rail, Freight and Ports division director, pushes back on the idea the agency isn’t making progress on intercity rail.He points out about half-billion dollars in Biden-era funding is investing in a new fleet of Amtrak Cascades trains and other needs to improve service. A new customs hall in Vancouver, B.C., will shave time previously waiting at the U.S.-Canada border, too.

There’s also the reality that, like many U.S. passenger trains, Cascades service operates “in the slipstream of freight,” Lang said, on tracks it does not own. It is a guest and plays second fiddle to the goods moving on Burlington Northern Santa Fe’s lines in Washington.

But more infrastructure work can be done to improve service, and now is the right time. Think about this dichotomy: Despite Amtrak Cascades runs being late more than half the time, ridership climbed to nearly 1 million passengers in 2024, an all-time high. While the service is subsidized by the state, customer fares covered 60 cents of every dollar spent to operate the Cascades, a figure nearly unheard of in the realm of public transit.

As a rider aboard Cascades many times, I’ve appreciated the quiet solace of the ride to get work done or relax as the world has gone by. Compare that to the stressful brake lights of Interstate 5, and I’ll take the train any day.

That also means taking the train doesn’t have to meet flight and road trip times exactly to be competitive. If the train journey to get to Vancouver and Portland is nudged toward more reliable, frequent and faster, imagine how popular the existing service becomes. Every marginal improvement — improvements in rail infrastructure like track siding, which allow trains to slip into a side pocket for others to pass — speeds both passenger and freight trains, a win for all. That also builds support for high-speed rail.

Last year, WSDOT released a preliminary plan for improving Cascades service over the next two decades. Disappointingly, it is less ambitious than a previous 2006 plan that included an aim of a 2½-hour journey to Portland from Seattle and one just under 3 hours from Seattle to Vancouver, B.C.

But some high-speed rail advocates point out that intercity passenger rail can only improve travel times so much, given the constraints of operating on a freight-rail line.

On top of that, the state Legislature is grappling with at least a billion-dollar transportation budget hole, which intensifies the perception that state leaders must pick one rail or the other: intercity rail or high-speed rail.

Senate Transportation Chair Marko Liias, D-Edmonds, rightly argues this is a false choice; the two systems are, and should be, on parallel tracks for federal and state funding.

The state senator compares the different kinds of rail to the tiers of a wedding cake. Each is needed to support the other.

In the same way, public support for all kinds of rail travel will grow when Cascades service improves.

To help, some lawmakers in Olympia argue WSDOT needs more genuine performance goals. Rep. Julia Reed, D-Seattle, introduced House Bill 1837 this session, which sets a 2-hour-30-minute goal from Seattle to Portland and 2-hours-45-minutes to Vancouver, B.C. It also calls for beefing up the number of train runs to 14 to Oregon from six; and five from two to B.C. Finally, it insists on snappier service: 88% of trains arriving on time, versus half today.

The bill is audacious, given funding realities. But the legislation re-centers and reprioritizes intercity rail service — a worthwhile cause. The bill cleared its first hurdle in Olympia Thursday, when it was approved by the House Transportation committee.

After all, lawmakers of every stripe should appreciate the intercity rail program. It has the potential to reduce passengers at a bursting Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, where 29 planes took off for either Portland’s or Vancouver’s international airports on Wednesday, as an example. It could also improve flow on a constantly choked I-5 freeway, reducing congestion and maintenance costs. Travelers by train, by the way, emit 80% less carbon per journey than their driving and flying counterparts.

The goal of ultra-high-speed rail must be achieved for the right reasons: moving passengers faster and more efficiently than in other ways, not because intercity rail service is deficient and substandard.

“If we want to see improvements we need to start early and we need to invest the time and the money that it takes to make those investments bear fruit in good time,” Lang told the transportation commission.

We can walk and chew gum at the same time. Let’s keep planning a greater vision for tomorrow, while pragmatically improving the rail service of today. The goal — faster, cleaner and more efficient movement of people and goods across our growing megaregion — depends on the success of both.

Josh Farley: 206-464-8275 or jfarley@seattletimes.com. is a member of The Seattle Times editorial board.