Washington state’s recently passed carbon-pricing legislation appears to be the nation’s most far-reaching state-level attempt to clamp down on greenhouse gas emissions.

It’s also likely to turn the state into a global testing ground for policy to combat climate change.

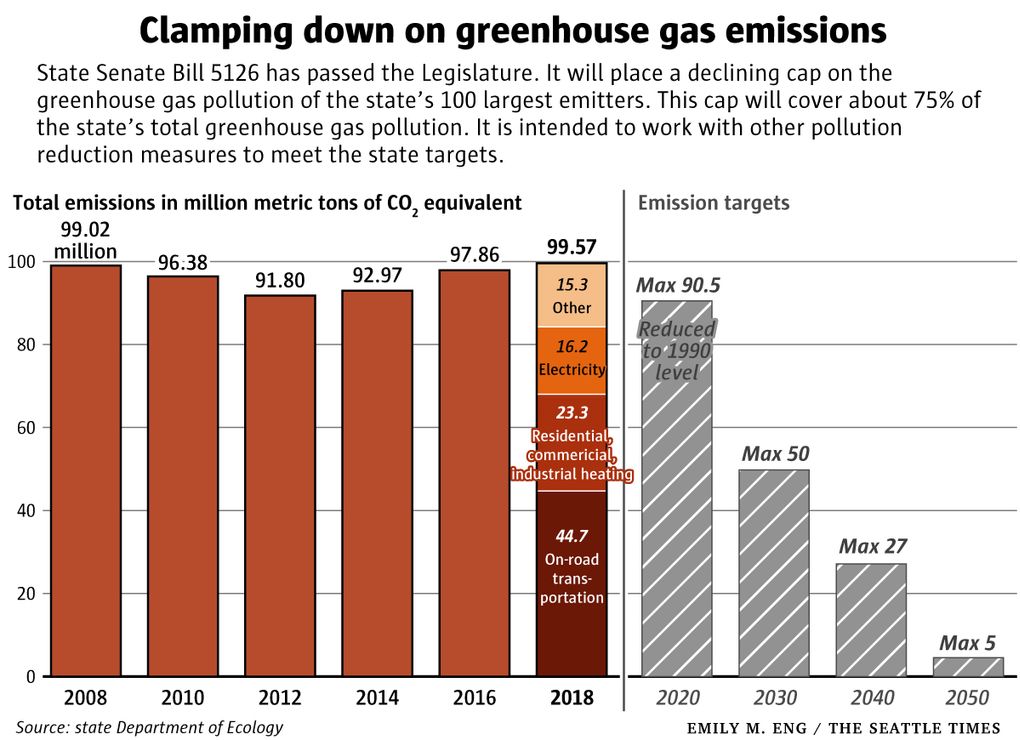

State Senate Bill 5126, headed to Gov. Jay Inslee’s desk for signing, is designed to help drive down pollution from 2018 levels of about 100 million metric tons to net zero emissions by 2050. That would require huge reductions in the use of fossil fuels in industries, as well as a near phaseout of gasoline and diesel fuel for cars and trucks. Much of the natural gas now used to heat many buildings would likely have to go.

The legislation is the culmination of a yearslong struggle by climate activists who often were not in agreement on how to proceed. The coalition that helped pass it eventually included not only many environmental groups but also powerful corporate players such as Puget Sound Energy and Microsoft, as well as BP, the state’s largest oil refiner, and some tribal governments.

Democrats used their majority control of the Legislature to pass the measure during an intense and historic finale to the 2021 session. Republicans, noting that Washington due to hydropower already has a relatively low-carbon profile, have fought a long-running battle to try to forestall what they view as laws that will unnecessarily push up the cost of energy for Washingtonians.

Rep. J.T. Wilcox, the Republican House minority leader from Yelm, calls it a “regressive tax and crushing blow to working families.”

The legislation, dubbed “cap and invest” by Democrats and “cap and tax” by Republicans, would require the state’s 100 largest emitters, including refiners, gas utilities and Boeing, to reduce pollution. Some of the emitters would have to pay for the right to release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

The bill is forecast to raise at least $460 million in the fiscal year that starts July 1, 2023, and at least $580 million annually by 2040. The money would be invested in a broad range of activities that include restoration of marine and fresh waters, forest health, renewable energy and public transportation. A portion of the money is set aside to assist workers and low-income people transition to a clean-energy economy, and some could be used to help fund the state’s working families tax rebate.

The legislation follows in the footsteps of a California law that put in place a tightening cap on greenhouse gas releases that contribute to climate change.

The California law, unlike Washington’s bill, will need to be reauthorized to extend past 2030.

Some of the stumbles in California’s implementation of its law were studied by Washington legislators as they tried to craft a bill able to result in the deep cuts in greenhouse gas releases required to meet the midcentury emission targets.

“I had a check list, and I made sure in my own head that we addressed these criticisms and weaknesses of the California bill, and not just danced around them,” said state Sen. Reuven Carlyle, D-Seattle, who introduced the Washington measure and was deeply involved in negotiations and redrafting efforts. “This was the central guiding principle of our work, and I never deviated from it.”

How it works

The Washington cap-and-invest legislation is scheduled to go into effect in 2023 — but only if the Legislature first passes a statewide transportation spending package that includes a way to pay for these road, highway and other projects through taxing and bonds.

The cap imposed by the bill covers about 75% of the total state greenhouse gas emissions.

It would be coupled with a 2019 law that requires a phaseout of carbon pollution from state power generation by 2045.

It also would work in tandem with another major bill passed in the final days of this year’s session that specifically targets transportation fuels — the largest source of state greenhouse gas emissions — by creating a clean fuels standard for marketers of gasoline and diesel, and would offer a large array of incentives to develop transportation fuels that emit fewer greenhouse gases and require the purchase of credits by fuel marketers that do not meet those standards.

The legislators who created the bill try to give certainty to greenhouse gas reductions by setting annual pollution limits for the state’s 100 largest emitters, which cover about 75% of the total Washington greenhouse gas emissions.

The state Department of Ecology each year will come up with an overall pollution allowance.

Another group of polluters will get most of their allowances for free, at least through 2035. This groups includes manufacturers considered vulnerable to out-of-state competition that could prompt them to move to another area with lower environmental standards.

Another key part of the bill charts the future of the natural gas industry, which delivers fuel for water heaters, furnaces and stoves in many Washington homes.

These utilities will get a declining number of free allowances, so they won’t have to bid in the auctions. If they pollute less than their permitted amounts, they can sell off their allowances but the money must be used to assist customers in conservation, shifting to cleaner fuels or other efforts that reduce emissions.

In a separate measure passed by the Legislature this session, gas utilities will have to go to the state Utilities and Transportation Commission and develop the most cost-effective plans for the dramatic emission reduction required by 2050. That could involve assisting customers to shift to electrifying their homes, or bringing in cleaner pipeline fuels such as hydrogen or renewable natural gas produced at landfills.

Puget Sound Energy is the state’s largest gas utility and was involved in the negotiations that led to the crafting of this part of the bill.

PSE this year set an “aspirational goal” of achieving net-zero emissions by 2045. And PSE, in a written statement, said that the company will work in partnership with regulators, customers and policymakers, to “create a clean energy future for all.”

“This is a recognition of what the science demands,” said Vlad Gutman-Britten, Washington director of Climate Solutions.

Washington “setting the bar”

During its development, Carlyle and other Democratic legislators received input from the staff of Environmental Defense Fund, which is now promoting the legislation as a national model. The provisions gaining attention are those that seek to combat air pollution effects in low income urban communities.

“I think this new bill is really setting the bar, in terms of the level of ambition,” said Nate Keohane, senior vice president at the Environmental Defense Fund.

It is a heady moment for Carlyle, a native of Bellingham who spent his teenage years as a congressional page for two of the state’s most renowned Democratic politicians, Sen. Warren Magnuson and Sen. Henry Jackson, and later worked in the cellular phone and software industries.

Last year, Carlyle decided to make another push for state carbon pricing at a time when support was at a low ebb.

Efforts to pass legislation had repeatedly failed. And in two separate statewide initiatives, in 2016 and 2018, voters soundly rejected a proposal for a carbon tax and then a fee on this pollution that would raise money for investment. The initiative campaigns made clear not only the hostile reception for carbon pricing in many rural areas of the state, but also sharp divisions within the climate activist community on how to structure such a policy and what should be done with the money.

Carlyle remained undeterred, and introduced a forerunner bill to the one that passed this year.

Inslee and environmental groups both declined to make the bill a priority in the 2020 session. Carlyle’s strongest ally appeared to be BP, which had poured money into defeating the 2018 carbon fee initiative, but backed his cap and invest approach with a two-week advertising campaign.

This year, Carlyle had broader support as Inslee made the bill one of his priorities. Also, Rep. Joe Fitzgibbon, D-West Seattle, who plays a high-profile role in shaping environmental policy in the Legislature, helped chart a course for the bill through the House.

“He (Fitzgibbon) started working on it last spring on policy concepts, and deserves a lot of credit,” said Gutman-Britten of Climate Solutions.

This divide over how to structure carbon pricing was one of the obstacles to passing this year’s bill. Some groups rallied around an alternative carbon tax bill amid serious concerns among some House and Senate members that the cap and invest bill did not do enough to address environmental justice.

These tensions resulted in changes to how some of the money raised by auctions would be spent, and how the bill would assist Washingtonians living in highly polluted areas.

Carlyle, in an interview this week, said he did have doubts that a climate bill of this scope would ever pass. He says he hopes it convinces other political leaders “to take the chance on going big.”