By

On Tuesday, Boeing will wave a final goodbye to the 747 jumbo jet.

In the years after its launch, the 747 elevated the Puget Sound region to the world’s premier airplane manufacturing site and boosted Boeing to preeminence in aviation. It made international air travel routine.

A diverse cross-section of the Boeing workers who helped bring this transformative piece of engineering to life tell their stories below. They reflect upon their affection for the jumbo jet that changed their lives, and aviation.

Almost exactly 54 years after the first flight, thousands of current and former employees and guests will attend a bittersweet ceremony in Everett on Tuesday before cargo carrier Atlas Air flies away a 747 freighter model, the 1,574th and last “Queen of the Skies” ever built.

Watch: Construction and first flight of the 747 in the 1960s

The final airplane will depart from outside the grand assembly plant purpose-built for the 747 in the late 1960s on what was then undeveloped land, the building not even complete as the first plane was assembled.

In time, that building would house more jet programs and grow to be the largest by volume in the world. Boeing Everett at a recent peak in 2012 provided more than 40,000 highly paid jobs.

The late Joe Sutter, chief engineer on the original program, led a team that designed, built and delivered the four-engined jetliner in such record time that they were nicknamed “The Incredibles.”

Sutter was given the task to design a new jet in August 1965. The first test plane rolled out of the newly built factory in September 1968 and had its first flight the following February. The first production plane was delivered to Pan Am on Jan. 22, 1970.

In this first widebody jetliner, economy passengers were seated 9 or 10 across and filed in along two aisles. It could carry 420 passengers, three times as many passengers as the prior 707 jet.

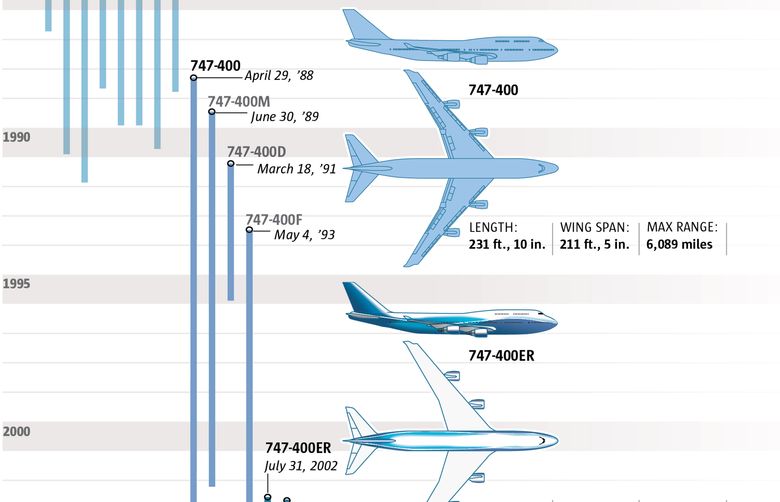

Later models grew in capacity and range so that the final 747-8 passenger version can carry nearly 470 people on trans-Pacific and other longer-haul routes.

From the 1970s through the ’90s though, the 747 opened up the world to millions who had never before traveled internationally.

Its range allowed airlines to fly nonstop between major cities never before connected. Its size produced economies of scale so they could fill seats at the back with cheaper fares.

Then, over the past two decades, airlines switched to the more fuel-efficient, two-engined 777. And so now, it ends.

Even air travelers otherwise ignorant of the differences between jetliners can recognize the 747 shape with its distinctive and somehow graceful forward hump, the pilots sitting high above the jet’s nose.

The shape is functional, designed to allow for a freighter variant with a unique feature: The nose of the 747 freighter flips upward like a gaping mouth so that outsized cargo nearly as long as the plane can be loaded through the front.

When orders for the passenger model dried up — five years ago, Korean Air was the last airline to take delivery of a passenger model 747-8 — demand for this freighter capability kept the 747 line going.

Once, while Sutter waited for his flight at Tokyo’s Narita airport during his creation’s heyday, he counted 55 Boeing 747s landing.

“I had just witnessed upwards of 20,000 people arriving in Japan within a span of two hours,” Sutter wrote in his autobiography. “We changed the world.”

Kelvin and Vic Anderson: Like father, like son

Kelvin Anderson is an Incredible, one of the original mechanics who built the first 747s in the 1960s.

His son Vic has worked on 747s for the past 34 years and, as team lead on the center fuselage, helped finish the last one.

The pair’s close bond was touchingly apparent as they bantered in November about their Boeing careers and the 747, then toured the assembly line.

Sprightly and trim at 83, Kelvin described a can-do culture that produced the 747 in the 1960s, an attitude he credits to inspirational upper management led by Sutter, the chief engineer.

His team, “close-knit” and determined, pushed forward at a frenetic pace.

“We worked a lot of hours, seven days a week, 12 hours a day for quite a while,” Kelvin said. “I don’t think we ever thought anything but success.”

At the rollout in 1968, he was “ecstatic along with everybody else.”

And when he saw it fly a few months later, “I figured when I’d seen that thing flying, we could fly anything.”

“I still get goose bumps when I see that thing take off,” Kelvin added. “It looks like it’s too big to fly.”

With just a high school education, Kelvin forged a long career as a top Boeing mechanic. For part of it, he served on a crack team that flew in to fix grounded airplanes.

In 1975, when a Japan Airlines 747 slid off a runway in Anchorage, tearing off the back end, he was on a team that spent 90 days working outdoors — “Thank God it was during the summer” — to take off the tail and replace the entire bottom of the rear fuselage.

Now retired in Ellensburg with his wife of 58 years, Kelvin said Boeing has given him a good life.

Vic, 56, clearly absorbed Kelvin’s positive attitude.

When Vic was 10 or 12 and security wasn’t as tight as it is today, he recalls, his dad brought him into the factory and inside a 747 being delivered to the Saudi royal family. “Everything was purple,” he remembers.

“Being around airplanes is all I ever wanted to be,” said Vic. As “a steppingstone” to Boeing, he joined the Air Force and became a crew chief on the F-111.

He’s worked on the 747 for all of his almost 35 years at Boeing. That meant learning multiple skills because, compared to other Boeing jets, far more of the assembly of the 747 is done in-house rather than by suppliers.

The final version of the jumbo jet, the 747-8, “has a lot of technology new and updated, but the actual build process of the airplane is old school,” Vic said. “Some of the tools that we use are some of the original ones they used when Dad was working on them.”

Kelvin retired in 2001 after almost 39 years at Boeing. Vic says he’ll stay five more years, “because I gotta beat him.”

And the aviation thread continues: In November, Vic’s son enlisted in the Air Force, aiming to be a crew chief like his dad.

The end of the 747 has come earlier than Vic expected. Before moving to a new job on the 777X, he asked to stay on the 747 until the last one rolled out.

“I thought I would leave before she beat me to the door,” Vic said. “I got four kids and all of them have grown up with this airplane. The 747 has provided everything I have.”

Thuylinh Pham: ‘747 always symbolizes freedom’

Thuylinh Pham, 35, a quality production manager, has worked on all of Boeing’s commercial jets. But the 747 is more to her than an airplane.

“To me, the 747 always symbolizes freedom,” she said.

Before she was born, after the Vietnam War ended in 1975, her father was imprisoned by the communist government for eight years in a re-education camp.

Years later, after he had rejoined his family and she was 3, the Catholic church sponsored the family of seven to come to the U.S.

“In February of 1990, we immigrated to America,” said Pham. “We flew over on the 747 and landed at Sea-Tac.”

Growing up, she recalls times when the family drove down Interstate 5 past Boeing Field and spotted a jumbo jet there. Her father would always declare: “Look, it’s the 747. It’s our freedom bird.”

The family has preserved the airline ticket that brought them here.

After the Phams reached the U.S., their story became one of typical immigrant striving and success — with many strong boosts from Boeing.

Pham’s father got a job as a maintenance technician with Seattle Public Schools, where, at 77, he still works. Her mother worked for 10 years as a janitor at Boeing.

“My oldest sister and her husband work at Boeing. And then my oldest brother also works at Boeing. And my second brother closest to me, his wife works at Boeing. I work at Boeing. And my mom retired from Boeing,” said Pham. “We’re a Boeing family.”

Remarkably, when Pham came back to the Pacific Northwest after college in Hawaii, before moving steadily up the career curve at Boeing, she started like her mother as a janitor.

“I was there for a few months,” she said. “I knew that I wanted to do more.”

Since then, Pham has worked on most of Boeing’s commercial jet programs, moving around among the company’s facilities in Seattle, Renton, Everett and Frederickson, near Tacoma.

At one point, “a manager who saw a lot of potential in me took me under his wing,” she said.

Pham was a first-line manager in interiors on the 777 and 737 programs, and a quality specialist investigating the cause of defects in 747 landing gear electrical wiring bundles.

She now manages quality inspectors.

“I’ve always been passionate about this company,” said Pham. “It’s given us the ability to be able to have a great life here.”

Johnny Patchamatla: Three generations

Johnny Patchamatla reveres his dad and treasures the link the 747 provides from father to son. His dad worked on the first plane; he worked on the last.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in India, his father, John Patchamatla, came to the U.S. on a scholarship to the University of Minnesota. He began his career in that state as a civil engineer and married an American.

In 1966, hired by Boeing, he moved his family to Seattle to work as an engineer designing components for the flight deck of a new plane: the 747.

John didn’t stay long at Boeing. Perhaps foreseeing the Boeing Bust that followed in 1970, he left before the first 747 was delivered. He worked for the city of Everett as a civil engineer for more than 30 years until he retired in 2003.

Yet the short Boeing stint “was a very instrumental part of his career in how the rest of our family lives would blossom and flourish,” said his son Johnny.

Before retiring at the end of December, Johnny clocked 21 years of service as a Boeing mechanic.

His brother-in-law was a 747 mechanic and is now a manager at Boeing. And his son, with 18 years at Boeing, is an engineer working on the KC-46 and AWACs military programs.

“It’s been a multigenerational and very fortuitous involvement for my family,” he said. “Chances are, the next generation might find themselves at this company as well.”

Johnny first joined Boeing in 1997 to work on 767 interiors but was laid off in the downturn that followed the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks in 2001.

In 2006, when his dad was dying, he thought about reapplying.

“He was so visibly relieved when I shared that with him. It really compelled my decision to come back,” said Johnny. “We laid him to rest a few days later, the day before I started back at Boeing.”

On the 747, he enjoyed the variety of the work, installing components primarily around the wings and engines.

“My dad’s involvement at the very onset of the program” — and his own role in closing it out — “was really meaningful for me,” he said.

“While I wasn’t able to follow my father’s footsteps in many ways throughout my life, this was one kind of deep connection that I’ll certainly take with me for the rest of my days,” Johnny said.

Darrell Marmion: ‘I’m retiring with my airplane’

Darrell Marmion, 59, retired in November as a top engineer after 36 years at Boeing, his hand forced by a pension glitch that would have cost him money if he’d stayed. He worked on about 800 Boeing 747s.

“I’m retiring with my airplane,” he said. “I’m actually glad at the timing, because I do care so much for the airplane.”

As for so many at Boeing, there’s a family legacy. His father, Henry “Hank” Marmion, who died early in 2020, was an “Incredible,” one of the original 747 team.

“One of my earliest memories in life was about 5 years old and my dad taking me on a tour of the mock-up of the first 747,” said Darrell.

Hank managed the team that built the mock-up of the 747 flight deck, working out how to fit all the instruments and cables as engineers designed the cockpit.

At the time, the 747 assembly plant on a newly developed tract of land in Everett was incomplete.

His dad “talked about driving up here on a mud road. The freeway wasn’t in yet,” said Darrell. “They were still working on the roof. When it rained they had to control the water.”

Despite the tremendous success of the effort to build the 747 in short order, the year the plane was delivered, 1970, brought hard financial times and layoffs: the Boeing Bust.

After four years working on the nascent jumbo jet, Hank elected to start over. He moved the family from Seattle to Yakima and became an apple farmer.

Clearly, though, Boeing had sparked a fire in young Darrell, who graduated from fixing stuff on the farm to fixing 747s. He ended his career as a Technical Fellow, one of Boeing’s engineering elite.

At Boeing, Darrell’s engineering role was to fix problems on jets being built, repair damage on finished jets and oversee modifications.

For many years in Everett, he’d go out every day to planes that had rolled out of the plant into the delivery stalls on the flight line to see if there were any rejection tags written — “It used to literally be a piece of paper with five carbons” — indicating something needed to be fixed.

“You’d walk in each of the stalls and see if there’s any paper in there for engineering,” Darrell said. “You pull it out, see what’s wrong, study the drawings, go understand it and go fix it.”

There was typically something to fix on the 747s.

“It’s not a digital airplane, not as accurate as the others [Boeing builds], so it takes a craftsman to build the airplane and get it operating properly,” he explained.

Darrell’ expertise led him onto big 747 projects. He spent several years in Taiwan leading the work to modify four 747s that became the huge Dreamlifter cargo planes used to transport 787 Dreamliner sections from suppliers around the world.

In 2016, Boeing named him Engineer of the Year for his work on another 747 project: figuring out what to do about dripping moisture in the passenger cabins of German airline Lufthansa’s fleet of new 747-8 jets.

Over two years of troubleshooting, his team worked out a solution and modified all 19 airplanes.

Darrell said he’ll be doing a lot of projects in his garage in retirement. Framed there is a poster from an early Boeing 747 ad campaign with the tagline: “An iconic, state of the art, enduring design.”

“That just captured it so well,” Darrell said. “You just look at the shape of it and you know what it is. It’s timeless and classic.”

Sherri Mui: Challenge accepted

Sherri Mui’s dad joined Boeing in 1979 to work on the 747. Her husband followed as a 747 structures mechanic in 1997.

In a visit on a day open to families of employees, Mui recalls, the inside of the factory made a striking impression.

“This place is ginormous,” she said. “And the size of our freight elevators — I’ve never seen any elevators so big. It was just amazing.”

“As soon as our son, our youngest, was in school full time, I said ‘OK, let me try to come here,’” she added. “And I got hired.”

Mui, 47, has worked on the 747 for the ensuing 15 years.

For the past six years, until December when the last 747 rolled out, she led a team on the assembly line that did “the last little finishing touches before it goes out to the flight line.”

Her team worked in the underbelly of the 747, installing the ceiling liners, insulation blankets, sidewalls and floor panels in the cargo bays and all the ducts and fairing panels in the air conditioning bay.

When the latest model of the jumbo jet, the 747-8, was being developed in the late 2000s, her team worked with the engineers to pre-fit the insulation blankets that line the inner walls of the cargo bays before the design could be finalized.

Mui recalls “the feeling of accomplishment of getting those all to fit in there and telling the engineers how it needs to be changed to make it fit.”

The installation work in the constricted space of the lower bays can be physically tough.

“Sometimes you’ll be lying down, drilling overhead, or sitting up squatting, or climbing into the sidewalls reaching overhead,” she said. “You’ll find muscles you never knew you had.”

And the concrete floor is hard on the legs. “The shins were the worst, the calf area,” Mui said.

By November, with just one last plane to finish, her team had shrunk to just 11 workers, who frequently joked to take the edge off the approaching full stop.

“I’ll give job assignments for the day, and we have a couple of people who’ll be like, ‘Oh, I’ll do it for you this one time, but don’t ask me to do it again,’” Mui said.

“You have a lot of people that get sad,” she added. “They know it’s the last time. This part will never be installed on this airplane again.”

Pio Fitzgerald: Passenger, pilot, problem-solver

Pio Fitzgerald boarded a plane for the first time at 5 years old, a Boeing 747 bound for New York from his native Ireland. The plane fired his imagination and came to shape his working life.

Less than three decades later, he led the engineering team that fixed a problem discovered during initial 747-8 flight tests, and, at 45, he’s now chief engineer for airplane systems at Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

Fitzgerald’s journey began on that first 747 flight, when his dad, with Pio in hand, charmed his way into the cockpit to talk with the pilots.

“From that day on, I wanted to be a pilot,” Fitzgerald recalled in a 2011 interview. On his 16th birthday, he took his first flying lesson.

During boyhood summer vacations, Fitzgerald flew regularly on 747s to the U.S. He’d write letters to Irish flag carrier Aer Lingus, reporting which flight he was booked on and asking to visit the flight deck.

Eventually, he earned a pilot’s license, an aeronautical engineering degree — during which he did an eight-month internship at Boeing in Seattle — a master’s degree and a Ph.D.

He joined Boeing on Sept. 23, 2005, delighting his Irish Catholic mother, for that was the feast day of Padre Pio, the saint for whom she named her son.

Fitzgerald was named 2011 Engineer of the Year at Boeing Commercial Airplanes as reward for fixing the 747-8. The problem was that in certain flight conditions, its wings vibrated excessively, a phenomenon known as flutter.

His multinational team of about 40 engineers devised a software solution.

In response to sensors on the wings that detect movements far smaller than what a human can perceive, software instructed the flight control computer to slightly raise or lower movable surfaces on the trailing edge of the wings to counter the motion.

The idea was to suppress the vibration before it was even felt.

To confirm if it worked, Fitzgerald rode along on a flight test in January 2011. Boeing test pilot Jerry Whites maneuvered the 747-8 into position. When the flutter started, he flicked a switch.

“We turned the system on and suddenly the road was smooth. We switched it off and it came right back,” Whites said. “It was magic. Absolutely brilliant. … I just wanted to hug the guy.”

Darrin Noe: Seeing the evolution of airfreight

While the 747 transformed international flying for passengers, the 747F freighter version of the jumbo jet essentially created the global long-haul air cargo market and led to Boeing’s dominance in that sector.

When the first 747 freighter was delivered to Lufthansa of Germany in March 1972, “the air cargo market really hadn’t been born yet,” said Darrin Noe, 52, a Boeing cargo engineer for 26 years. “The 747 sort of helped propel the whole industry direction.”

The Boeing widebody freighters that followed — the 767F and the 777F — took design components from the success of the 747F.

“If you go onto even our latest freighters … you’ll see pieces that look exactly the same as for a 747,” said Noe.

What makes the 747 freighter so in demand is its unique nose door, which flips upward to open a gaping maw almost 12 feet wide and 8 feet high that runs the length of the plane.

“It allows the 747 to do things another plane can’t really do,” said Noe.

He’s seen “2,000-and-some-inches-long loads” — that’s 56 yards long — delivered on multiple loaders and fed through the nose into the vast space inside the 747F.

The plane is a heavy hauler, moving military vehicles, loads of cars and large equipment such as drilling rigs.

“It’s hard to get those put on to anything else without breaking them down,” Noe said.

In recent years, he’s seen more high-value cargo on 747Fs, including expensive vehicles such as “Mercedes-Benz with silver plating for trim. Maseratis.”

In 2018, Cargolux flew race horses from Luxembourg to the Asian Games in Indonesia on a 747F.

For livestock, the cargo hold temperature and airflow are carefully controlled. And animal handlers are on board, either in the stalls with the animals or in the four business-class seats in the 747’s upper deck hump, just aft of the cockpit.

The cargo version extended the life of the jumbo jet. For the final 747-8 model, 70% of those built were freighter planes.

Based in Everett, Noe said he routinely walked past 747s in the factory.

“Going through there now and seeing the majority of the tooling already being removed, it’s a little empty,” he said as the final 747 readied to roll out in November. “It leaves me a little teary-eyed.”