Fifteen times during each school day, an IRT subway train would rumble and screech past Public School 98, near the northern tip of Manhattan. In classrooms facing the elevated tracks, all work would stop until the train barreled by.

After years of complaints about the disruption, the Transit Authority cushioned the rails with rubber pads, and the Board of Education outfitted the classrooms with sound-absorbing materials.

After the noise-abatement steps were taken, the reading levels of the youngsters improved as much as a full grade level. This distinctly New York achievement story is reported in the current issue of the Journal of Environmental Psychology by Dr. Arline L. Bronzaft, professor of psychology at Herbert H. Lehman College in the Bronx and a consultant on noise abatement for the Transit Authority. ‘Interferes With Learning’

”The results clearly show that noise interferes with learning and that the abatement of noise improves a child’s ability to concentrate and learn,” Dr. Bronzaft said in an interview yesterday.

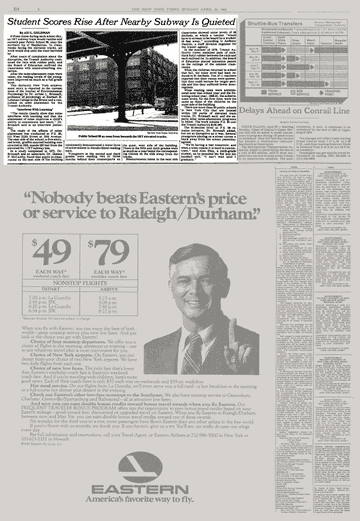

The study of the effects of noise abatement was conducted at P.S. 98, 512 West 212th Street at 10th Avenue. The east side of the school, a five-story, red brick, graffiti-marred building constructed in 1923, stands 220 feet from the elevated No. 1 IRT subway line.

In a study completed in 1975, Dr. Bronzaft and an associate, Dr. Dennis P. McCarthy, found that pupils in classrooms on the east side of the building consistently demonstrated a lower level of achievement in standardized reading tests.

Youngsters in the second and third grades were reading two to three months behind their counterparts on the quiet, west side of the building. Those in the fifth and sixth grades were as much as a year beind the corresponding classes on the side away from the tracks. Teaching Time Down 11%

Measurements taken in the east side classrooms showed noise levels of 89 decibels, at which a teacher ”would have to scream to be heard by a student 16 feet away,” according to Anthony Paolillo, a staff division engineer for the transit agency. Each day, 11 percent of teaching time was lost in these classrooms, according to Dr. Bronzaft.

In the summer of 1979, Transit Authority crews installed pads of inch-thick butyl rubber between the rails and each railroad tie. In addition, the Board of Education placed insulation panels on the ceilings of the noisiest classrooms.

When the children returned to school that fall, the noise level had been reduced to 81 decibels. Ten of 11 teachers reported that their rooms were quieter, that they could lecture for longer periods and that they suffered fewer interruptions.

When reading tests were administered later that school year and the following school year, 1980-81, the achievement levels, for the first time, were the same as those of the children on the quiet side of the building. More Programs to Follow

There are more than 50 public schools in New York City that are located within 150 yards of elevated train tracks, Dr. Bronzaft said, and she expects other noise-abatement programs to follow. The work outside P.S. 98 cost the Transit Authority $100,000.

The 81-decibel level at P.S. 98 remains intrusive, Dr. Bronzaft added, but not as disruptive as it was. Several youngsters playing on a street corner a block away from the school yesterday agreed.

“We’re having a test tomorrow, and when a train comes it is hard to concentrate,” said Alex Diaz, a sixth-grade student, as he pounded his fist into his baseball mitt. ”I can’t wait until I graduate.”