Summers are not what they used to be in Seattle or its suburbs.

Around Lake Washington, trees are rapidly being replaced with a growing density of concrete, asphalt and other heat-absorbing surfaces in buildings, roads and other pieces of urban infrastructure. That produces what’s known as an “urban heat island,” and it’s boosting temperatures around the Emerald City by at least 8 degrees Fahrenheit.

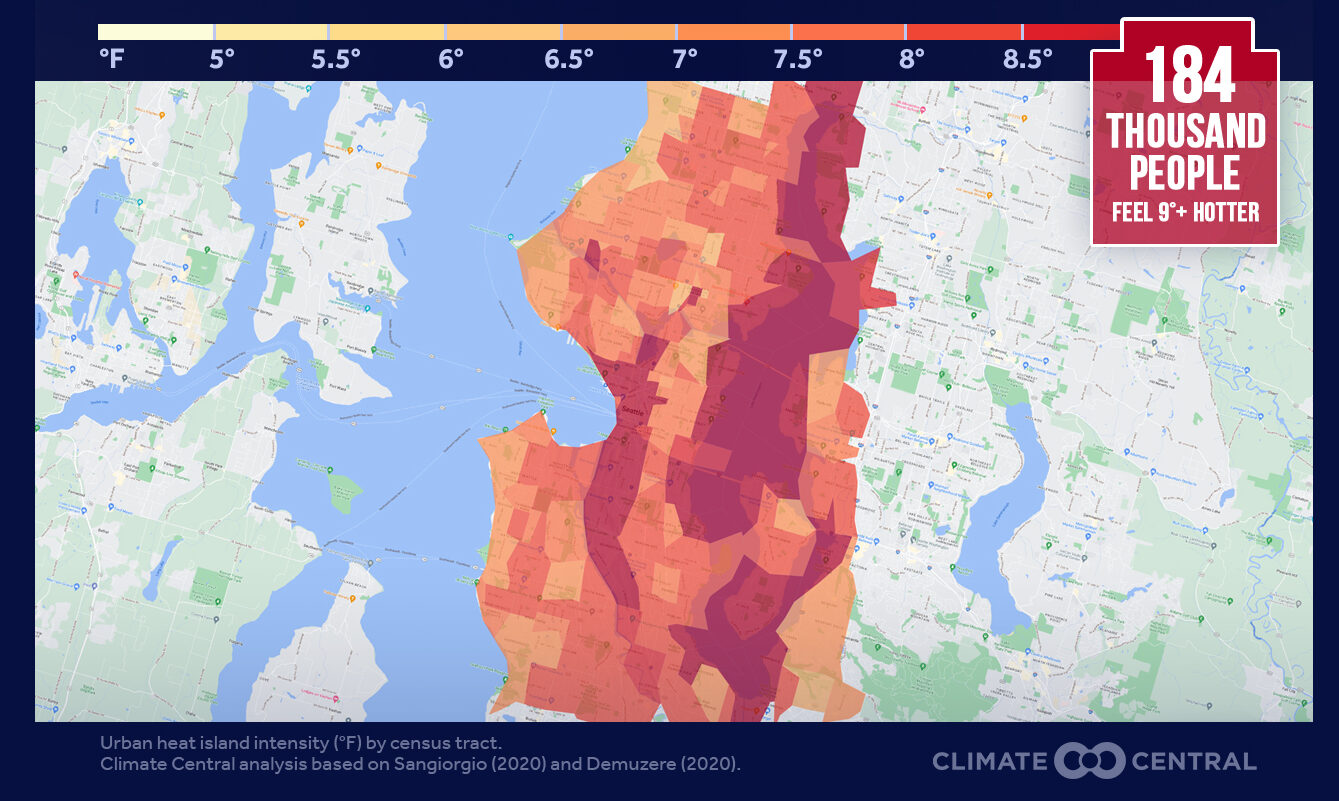

About 80% of area residents, even those in verdant, affluent neighborhoods, are now exposed to heat extremes much worse than the city’s rural surroundings, according to a new study by Climate Central, a nonprofit, climate-science research organization.

“Most of the planet is warming due to human-caused climate change, but the built environment in cities amplifies both average temperatures and extreme heat,” the study said.

By a wide margin, heat is the deadliest natural hazard in the U.S., and heat waves are growing hotter, longer and more frequent as climate change progresses, putting children and older adults especially at risk.

Among the 44 cities Climate Central analyzed, Seattle ranks in the top five for increased heat.

Using an urban heat index, the study contrasted ambient air temperatures in urban areas with those in rural areas. That estimate shows how much additional heat the built environment captures in each census tract across the studied cities.

More than half of Seattle’s population resides in areas where daytime temperatures are over 8 degrees hotter than they would naturally be, making a 90-degree day feel like 98 degrees. About 20% live in areas with a difference of over 9 degrees, and nearly 10% are in parts of the city recording a heat increase of over 12 degrees.

Since these surface areas retain heat, nighttime temperatures can be 2 to 5 degrees hotter than surrounding areas.

The study essentially shows how city residents are living in different thresholds of heat relative to their rural environs, said Vivek Shandas, professor of climate adaptation at Portland State University, who is familiar with the Climate Central report.

Seattle’s high ranking is the result of the rural forested landscape that surrounds it, Shandas added. That’s why Phoenix and Albuquerque, N.M., surrounded by desert, rank lower.

“When you compare a highly urbanized area to a forested landscape, the trees absorb a lot of that solar radiation. They’re moist, it’s shaded and you end up getting a much lower average temperature,” Shandas said.

Much like Los Angeles, the heat intensity in Seattle spreads across the developed urban expanse, beyond downtown all the way to Tacoma, according to the study. By contrast, the intensity in Albuquerque or Colorado Springs, Colo., is concentrated at a core, while in cities like Chicago or Atlanta, the heat gets diffused to zones reducing their difference from rural areas.

While the Climate Central report gave a census tract-level overview of heat in the Seattle area, another study from 2020, co-authored by Shandas, offers a granular view of who is most likely to feel the impacts of a warming Seattle.

That study examined what are known as intraurban heat islands — pockets within a city that are measurably hotter than other parts of the same cityscape.

Shandas’ study observed heat patterns in 108 cities at a hyperlocal scale and compared these with 1930s redlining maps, or cartographic records of racist economic segregation in American cities, including Seattle. Nonwhite neighborhoods were marked on the maps — “redlined” — and denied public investment dollars as well as access to home loans.

Nearly a century later, heat island maps echo their legacy.

“We didn’t compare it to the rural areas, we compared it just within the city at the same hour and found about a 20-degree difference,” Shandas said.

While the neighborhoods as a whole may be cooler than the downtown core, small sections get far, far hotter. And those sections are more likely to be home to people of color.

“What we found was pretty consistent with a lot of environmental justice that has been going on in King County — neighborhoods along the Duwamish, Tukwila, South Seattle and Rainier Boulevard were much hotter than areas in North Seattle like Green Lake or Magnolia, or even downtown.”

Even today, these areas with fewer natural landscapes are losing more green cover than the citywide average.

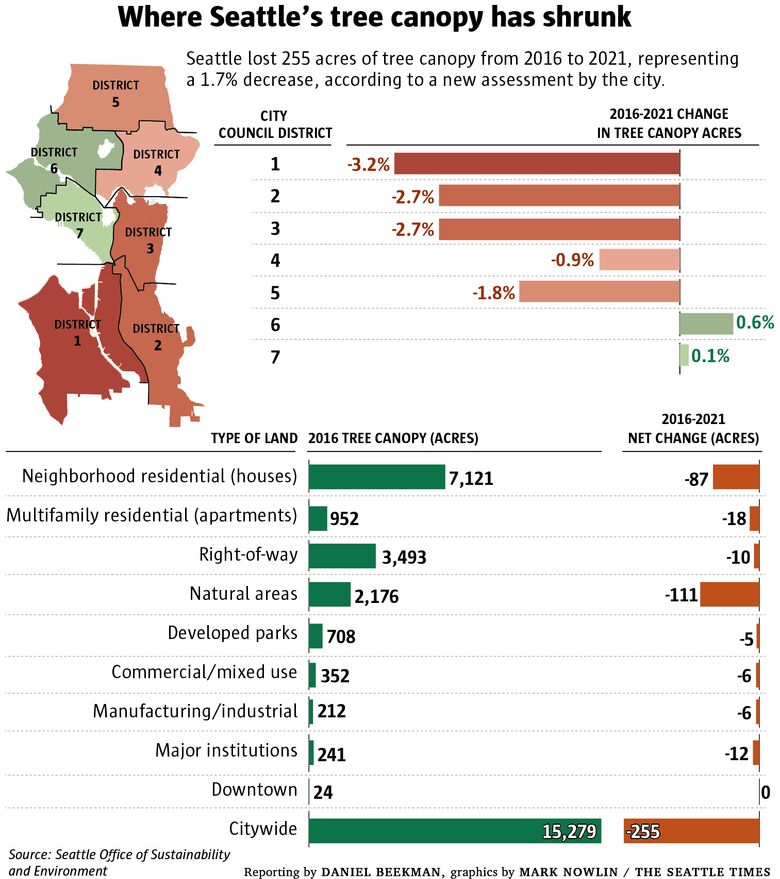

From 2016 to 2021, the city lost 255 acres of tree canopy, mostly in natural parks and residential areas — many of which had less to begin with, according to a city assessment. For perspective, the Washington Arboretum is 230 acres in size.

While environmental justice efforts have led to some canopy gains in these neighborhoods, the losses outpaced the gains, the report found.

By providing shade, soaking up solar radiation and trapping water, trees and vegetation can lower surface and air temperatures 20 to 45 degrees.

Formerly redlined areas also suffer from a style of construction likely to trap heat. Buildings are more likely to be low and broad, and they feature concrete and asphalt surfaces. Dark roads also absorb a lot of heat, exacerbating heat extremes.

“In downtown Seattle, there are a lot of high-rise towers that, believe it or not, actually shade the roads and keep temperatures in the downtown area a lot cooler,” Shandas said.

High-rises near the waterfront also prevent inland wind flow.

Of course, the Pacific Ocean does have a moderating effect on Seattle’s overall climate, keeping daytime and nighttime temperatures cooler than inland areas.

However, the city can’t escape global warming, said Jessica Halofsky, director of the Northwest Climate Hub and Western Wildland Environmental Threat Assessment Center at the U.S. Forest Service.

“Overall, if our whole planet is warming, we’re still going to see increases,” Halofsky said, adding that the Northwest’s coldest days are already getting warmer.

Surrounded by water bodies that absorb a lot of heat, the Pacific Northwest has traditionally not had to consider heat and wind flow in its urban planning and design.

Unlike other weather events like storms and floods, heat is an insidious, silent killer, Shandas said. Extensive exposure to heat wears people down over time. “It’s like death by a thousand cuts — so when an extreme event like the heat dome of 2021 comes through, that can be the fatal blow.”