IF YOU’RE AN ADULT in Western Washington, there’s a 50/50 chance that you flew out of Seattle-Tacoma International Airport in 2022.

The specific statistic for this region is 2.4 million adults, or 54%, according to the market research firm Nielsen Scarborough.

So, yes: Sea-Tac is a very familiar place for us locals.

It also is a 24/7 enclosed city run by a population equivalent to Kenmore or Oak Harbor. As of April, that’s 23,329 people with security badges allowing various kinds of access.

You’ll find some of these workers in the giant basement — no sunlight here, and not open to the public — which has 10 miles of conveyor belts transporting your baggage.

And in a large basement room lined with screens monitoring 3,800 cameras placed pretty much any place you look up at the airport.

And at the Salty’s at the SEA restaurant, with a name that plays on its seafood fare and location. It knows time is crucial and will provide you with a freshly cooked seafood scramble breakfast in seven minutes. In the back, TV screens track the orders. When an order is pushing deadline, the type starts turning red.

SEA-TAC HAS come a long way from its opening on July 9, 1949. It was built on scrubland and property bought from 264 individual owners. In its first full year of operation, some 500,000 passengers went through the airport. In 2022, that figure was more than 90-fold: 46 million.

On Yelp, Sea-Tac gets 3½ out of 5 stars from more than 3,200 reviews. It’s a judgmental world.

Alden from Tacoma writes in his four-star review, “Truth be told, I don’t have any major beefs with this airport.”

Yes, there are times such as the horrendous week beginning Dec. 21, 2022, when a winter storm canceled or delayed more than 800 flights. Still, in 2022, for on-time arrivals, Sea-Tac was rated No. 8 among all world airports. The global aviation analysis firm Cirium puts its on-time figure at 81%.

OVER SEVERAL DAYS, I visited with a few of the individuals who make the airport work.

Let’s begin with Port of Seattle police Officer Emily Holdeman, 37.

She’s going on two years here. Before that, she was with Issaquah police, and before that, she was a social worker with the state’s Child Protective Services. She graduated from Washington State University with a degree in criminal justice.

When I interview her, she looks up her electronic counter to see how many steps she had walked the previous day. It was 17,152 steps through the airport. This is her beat. By her estimation, that’s 7.6 miles.

There is a lot of walking at Sea-Tac. Ever puffed your way through Concourse A, used by Delta and United? It’s 2,172 feet long, two-fifths of a mile.

Holdeman has helped a man who had collapsed until the medics arrived. She decides whether an unattended piece of luggage “looks weird” enough to have a dog take a sniff.

Really, all she has to do is stand there, and a lost passenger will walk up with a question. A smile, a friendly voice help.

Holdeman wears 23 pounds of gear, which adds heft to those 17,152 steps. That includes a Glock 17 9-mm pistol (never used at Sea-Tac). Two pairs of handcuffs. A Taser 7 that shoots out 50,000-volt probes (also never used). Narcan nasal spray, which can reverse opioid overdose (used once, for a man found unconscious in a lavatory after using fentanyl) and a Narcan spit hood (not used in this case).

Holdeman is asked about some memorable encounters she’s had.

On March 11, a passenger was sleeping in baggage claim. “He got his vintage violin stolen, along with his passport, iPhone and iPad,” she remembers. “My partner and I were able to track the violin using a Find My iPhone app to International Boulevard. We arrested the thief and got the violin back.”

ABOUT THOSE 3,800 cameras.

Susan Lee, a senior operations controller at the airport’s communications center, is in her 30th year.

“My gosh, the technology. It’s changed,” she says. When she started, “There was fire dispatch, and that was pretty much it.”

There now are 20 people in the team, spread to work 24/7.

They can see when one of the underground trains connecting the Sea-Tac satellites has malfunctioned, resulting in passengers having to disembark and take a bus.

In the center, an array of monitors flips through images captured by the cameras. From showing 24 separate views on a 6-foot-wide screen, a simple command can switch to one huge view.

In the room, it goes from the routine to, “We have to jump,” says Lee.

On Sunday, March 18, a call came in to the communications center about two suspicious roller bags and what appeared to be an orange toolbox by the Alaska Airlines check-in area. When an airport cop arrived, he was told that nearby was a 4-foot PVC pipe sealed at both ends with shrink wrap.

The officers reviewed video footage. They evacuated the nearby area. A dog that can sniff explosives was brought in, as well as a bomb disposal robot. An airport cop announced, “Everyone, please back up; there’s going to be a little boom.”

There was a bang, and the police report says, “The items were disrupted,” meaning they were blown apart.

It turned out the two bags contained scuba gear, and the pipe contained a fishing pole.

The couple who owned the bags was tracked to their destination in Albuquerque. The port says they didn’t want to pay extra to take them on their flight and left them behind. The port’s police report concluded the incident created “a major delay in operations,” but no crime was committed.

THERE IS A reason Sea-Tac has “International” in its official name. In fiscal year 2022, which went through last September, 1.8 million passengers arrived from abroad who hadn’t been precleared at their departure city, such as Dublin and all Canadian cities except Victoria and Kelowna.

Upon arriving from a 12½-hour direct flight (Istanbul to Seattle), after picking up their luggage, passports in hand, these new arrivals are assessed by one of 400 to 500 Customs and Border Protection officers who work here.

What are these officers looking for? What can trigger a second look?

“Hands trembling, avoiding eye contact … it’s a totality,” says Rene Ortega, the CBP port director. But, he says, “Sometimes people get nervous for no reason. Ninety-nine percent are legitimate travelers. It’s that 1% we’re looking for.”

On this particular day, a beagle named Buckie, and his handler, CBP agriculture specialist Vicmary Acosta, are going down the line of international arrivals.

Buckie is about to turn 2, Acosta says, and spent eight weeks at the USDA’s National Detector Dog Training Center just outside Atlanta, training to hunt for agriculture products. “He’s doing pretty good,” says Acosta.

Jodi Daugherty is a trainer at the center. In a phone interview, she explains, “Beagles are bred for their noses. They’re friendly; they’re small and easy to maneuver around all the passengers.”

At first, a dog like Buckie is trained on five basic scents: apples, citrus, mango, beef and pork, all considered “universal targets” at ports. They’re homes for “fruit flies, weevils, African swine fever we don’t want coming into this country,” says Daugherty.

Eventually, the dogs can be trained on 150 scents. Why not? One study says dogs have a sense of smell 10,000 to 100,000 times more powerful than that of humans.

On this day, Buckie is particularly excited when sniffing a fanny pack carried by a man who had been on the Istanbul flight. He opens it. It contains dates and cheese the man had snacked on. The man laughs. Buckie and Acosta keep going down the line.

At an inspection station, Alice Sesay, of Seattle, returning from visiting family in Sierra Leone in West Africa, has her luggage manually searched by a CBP agriculture specialist as well as one from U.S. Fish & Wildlife.

Sesay has packed traditional foods, such as caffeine-containing kola nuts, listed as generally safe by the FDA.

Opened up, the kola nuts are deemed safe from carrying a disease. “The leaves are dry enough,” one of the specialists says. Sesay goes on her way.

Nearby, another dog, named Zofo, is trained to sniff for currency and firearms. Dogs can be trained to smell the volatile compounds in the ink and paper used in bills, according to a 2003 study in the Journal of Forensic Science.

International travelers must declare any amount over $10,000, whether arriving or departing. And if they go over that amount? “Most of the time, we give them the opportunity to amend their declaration,” says Ortega.

But the deal is, if you say you’re carrying $9,000 but it’s, say, really $30,000, and you are asked whether you want to amend but don’t and then $30,000 is found … well, it’s all seized.

The CBP says that in the 2022 fiscal year at Sea-Tac, it seized $1.5 million in 45 inspections of people leaving the United States. That averages out to $33,000 per inspection. (I filed a Freedom of Information Act request for the 2022 amount seized from people arriving from abroad into Sea-Tac. The U.S. Treasury replied that the Bank Secrecy Act prohibited disclosure of such information.)

AIRPORTS INHERENTLY ARE places with lots of baggage. The airport’s fire department says it sometimes has to treat passengers who trip while juggling baggage on an escalator.

Last year at Sea-Tac, it handled 14.5 million pieces of baggage.

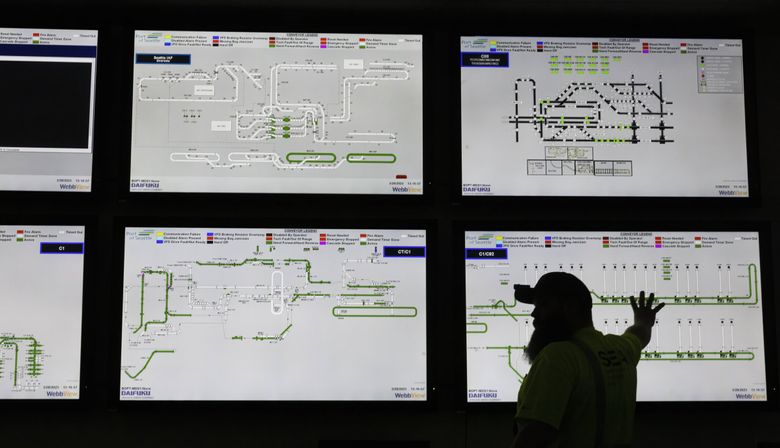

John Kier is a foreman in the baggage control room, also in the basement and with artificial light. He is surrounded by 10 big monitors. Some of them show bags moving along those 10 miles of conveyor belts.

Another bunch of monitors shows the belts as lines colored green, which means all is going smoothly. Lasers along the route scan the bar codes that are attached to each piece of luggage. The computerized system uses sorter arms to put them on the right track.

If all goes well, no human will touch the luggage from the ticket counter to when it’s loaded onto the plane.

But then a segment turns red. The video of that segment might show a piece of luggage that got stuck — maybe a strap jammed something, maybe a sorter arm is stuck.

The monitors have changed things, says Kier.

Before, “We were flying blind. We didn’t have all this camera access. We didn’t have a live feed.”

ALL THESE BAGS go through TSA machines that look a bit like an MRI machine.

If the initial screening shows something suspicious, the luggage is diverted to a room where Transportation Security Administration officers take a closer look using 3-D technology. They can virtually rotate an object, take a virtual slice of it and zoom in on it, with 5% then opened and checked manually.

You’d need to be at least in your late 20s to remember a different, less suspicious time at airports. That was before you had to take off your shoes or get patted down if the full-body scanner beeps.

The TSA was created in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, and there are more than 850 TSA security officers who work at the airport.

Compared to images that scanners showed a few years ago, says Ed Brabant, the TSA transportation security manager at Sea-Tac, “Today’s resolution is mind-boggling.” The images are like those from a science fiction movie, but real.

Besides the checked luggage, there are carry-on bags. In 2022, nearly 17 million passengers went through TSA checkpoints on the way to their flights, and it’s here where the majority of the agency’s officers work.

The TSA doesn’t track how many carry-ons there were, but the number is certainly a variation of how many millions.

Aeron Vo, 25, is one of the officers. On this occasion, he’s dealing with a passenger who didn’t have his boarding pass handy and was shuffling through his pockets for it. In the course of that, the man dropped a bunch of coins on the floor, which further flustered him. Vu helped pick up the coins. The man went on his way.

It is weapons that the agents are looking for in your carry-ons.

And they’re finding them.

In 2022, a record 113 firearms were found in carry-on bags during routine X-ray screenings. That’s compared to prepandemic 2018, when 81 were found. Nationwide, 89% of the firearms found in carry-ons are loaded, and most have one chamber ready to go.

April 6 was a busy morning for finding firearms at Sea-Tac. A 59-year-old man was packing a loaded .45-caliber Smith & Wesson. He said he forgot it was in the carry-on. A 31-year-old woman had a loaded 9-mm Sig Sauer P365 handgun. She also said she had forgotten it was in the carry-on. A traveler and his son flying to Maui had a BB gun. The adult said he didn’t know the son had packed the gun, and chose to have port police destroy it.

None of these three was charged under a state law that says for there to be a violation, a person has to “knowingly” possess weapons prohibited in certain places.

NOW, LET’S MEET a 16-year Alaska Airlines customer service agent at the airport.

Sea-Tac is the hub for Alaska, with 54% of the airport’s passengers flying on that airline. Alaska and Horizon Air, a subsidiary of Alaska, employ 7,500 at the airport.

After jobs that included being a blackjack dealer in Reno, then radio advertising, then upholstery sales, Susanna Poier answered an Alaska classified ad in this paper, back when there was such a thing.

It doesn’t hurt to have such a wide background when dealing with all those passengers.

Recently, a woman in her 30s, flying to Nashville, was looking for her gate. The woman began telling Poier what has happening in her life. “She had a horrible fight with her fiancé, and she was going to try and make things right with him, and mend the relationship. She was crying,” says Poier.

Perhaps the woman simply needed someone to listen. “She walked away a little more hopeful.”

Poier has the nickname “the intox whisperer.”

Whether someone seems intoxicated at the departure gate, or Poier is called to talk to someone already on a plane, “I never embarrass a guest. I try to be diplomatic,” she says.

She tries to get them to leave the plane. “Let’s chat outside.” She’ll get them rebooked on the next flight, “let them have something to eat.”

On occasion, the individuals realize it was for the best. “I’ve gotten hugs,” says Poier.