Jack Block, who in his 28 years on the Port of Seattle Commission helped transform Seattle’s waterfront from a rat-infested row of crumbling piers into a destination for massive container ships, cruise vessels and tourists, died Nov. 1 of cancer. He was 86.

Block, the only longshore worker ever elected to the commission, also holds the title of longest-serving commissioner.

Between 1974 and 2001, he espoused advances in cargo mechanization, wooed shipping lines to Seattle and gambled on a major investment in cruising — which became, before the pandemic, a $900 million-a-year boon for Seattle’s tourism economy.

Block deserves much of the credit for how Seattle’s waterfront looks today, former colleagues said. In the 1980s, he pushed a major waterfront redevelopment plan through the commission when public meetings and feasibility studies threatened to filibuster it out of existence, according to contemporary news reports.

The port has “an obligation to do something with this waterfront … [which] quite frankly looks like somebody’s armpit,” he said at the time.

Close to Block’s heart, said his son Jack Block Jr., were projects to protect the environment, including cleanups of Superfund sites at Terminals 5 and 18, and to expand public access to the Duwamish River shoreline. Those efforts culminated in the 2001 dedication of Jack Block Park on the site of a former creosoting plant at the river’s mouth.

Block remained a longshore worker throughout his nearly three decades on the commission, allowing him to boast that he was the only commissioner who could operate every piece of equipment the Port owned. By day, he attended to Port business; by night, he worked as a foreman on the docks, where he was known as a formidable taskmaster, said his longshore colleague Kandi Kandi.

“The thing my father was most proud of was being a longshoreman,” said Block Jr., also a longshore worker. Block was one of Seattle’s first crane operators and at 31 became the youngest foreman in the history of his union.

Block’s time on the commission was not without controversy. By the late 1990s, he had lost the support of organized labor — including some longshore workers — over his backing of the Port’s new commercial real estate ventures and his acquiescence to the Port’s decision to contract out some work, like crane maintenance. In his 2001 reelection bid, the powerful King County Labor Council backed his opponent, sinking Block’s candidacy.

“His main issue was creating a balance between preserving the waterfront land for some marine use, or have it sitting there doing nothing,” said his second wife, Vicki Schmitz-Block. “He honestly felt that it was better to develop the land than have 10 longshoremen working on a 10-acre plot.”

Block, whose lengthy tenure led newspaper columnists to refer to him jokingly as “commissioner-for-life,” was also on the commission during a string of revelations about double-dealing and conflicts of interest at the Port. Challengers for his seat tended to paint him as a backroom dealer opposed to making the Port more public-facing, though Block was never explicitly accused of improper behavior.

Born near the end of the tumultuous 1934 waterfront strike that resulted in the unionization of all West Coast ports, Block grew up fishing off Seattle’s docks and accompanying his longshore worker father onto ships, he recalled for an early-2000s television segment on the Port of Seattle.

His father, though, envisioned a different future for the young Block, banning him from longshore work. Block flouted his father’s interdiction and got a job on the docks at age 15, but bent to his father’s wishes in one respect: He earned a degree in international trade from the University of Washington, a background that later proved helpful in negotiating with foreign officials on international trade trips, his commission colleagues said.

Block unsuccessfully ran for public office four times before winning a seat on the commission in 1973. He lost his first three bids for the Port Commission in 1965, 1969 and 1971, running on a promise to mitigate noise pollution near Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. (Block was later the commission’s sole vote against construction of a third runway at the airport.) He also made a quixotic 1966 bid for the state Legislature on such a shoestring budget that he handed out shoestrings to voters.

But after joining the commission, he was reelected four times — even, by the 1990s, winning over the business interests that had refused to back his initial runs.

Colleagues on the commission recall his twinkling grin — as a toddler, Block’s chubby cheeks had won him the title of Carnation Milk’s Baby of the Week — as well as his love of travel and oddball sense of humor. In the late 1980s, he worked so closely with the Port’s first female commissioners, Pat Davis and Paige Miller, that he started calling the group the “three buffalo,” after a painting hanging in the commission office of three buffalo with their heads together, Miller said.

Davis said Block believed the Port functioned best when staff had leeway to innovate in response to competition from Californian and Canadian ports.

Block “understood that … the commission is supposed to hire someone to do management, and not stick their fingers in his eye on a regular basis,” Davis said. “Jack was willing to keep the Port moving and take advantage of opportunity.”

Block believed bringing cruise ships to Seattle and speeding up efforts to mechanize cargo operations would ultimately benefit longshore workers. But at the time, some saw mechanization and cruising as threatening dockworkers’ traditional role on the waterfront.

Even more controversial among the longshore community was Block’s backing of the Port’s commercial real estate ventures in the 1980s, including the construction of the new cruise-ship terminal, a pleasure-craft marina, condos, office space, the World Trade Center and the Port’s new headquarters.

“We used to build up the port as a seaport,” retired longshore worker Arthur Mink told historian Walter Crowley in the early 2000s. “Now the Port Commission has become totally inhabited with people from the financial district. Their interest is not in promoting cargo. Their interest is in real estate.”

Block believed that to thrive, the waterfront needed to change — a position that meant he was bound to lose the support of the union eventually, said Herald Ugles, former Seattle longshore union president.

“When you have someone of your own in a position of power, you expect that they’re going to do everything that you want them to do,” he said. “Jack Block told us what he saw as the truth, and that didn’t make the union very happy.”

And what some characterized as a pro-business attitude, others saw as a lack of oversight. A 2007 performance audit that reviewed some contracts signed while Block was still on the commission found the Port’s lax contracting management had left it “vulnerable to fraud, waste and abuse.”

After Block left office, transparency became the watchword for Port Commission candidates. When Block’s son made a 2007 bid for the Port Commission, he pledged to eliminate no-bid contracts, halt the development of pleasure-craft marinas and end the Port’s investment in commercial real estate.

“I am not my father’s son, politically,” Block Jr. told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer at the time. He lost that race to Gael Tarleton.

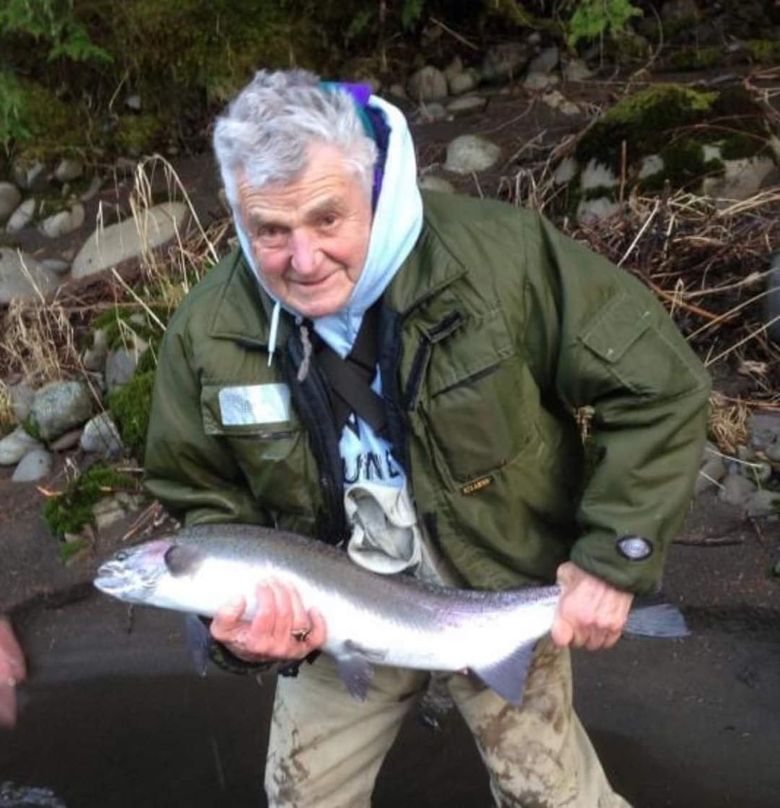

After leaving the commission, Block lobbied the Port on behalf of Sea-Tac businesses, represented local longshore pensioners to the national convention, fundraised on behalf of the Port of Seattle Firefighters and the Seattle Seafarers Center and greatly indulged his love of fishing.

Block was preceded in death by his first wife, Fran. He is survived by his second wife, son, daughters Heidi, Natalie and Joey, six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

The family will hold a public memorial after the COVID-19 pandemic and asks that donations be made in Block’s name to the Washington State Council of Firefighters Burn Foundation, the Seattle Seafarers Center or Long Live the Kings, a salmon restoration nonprofit.