![]() Donald G. McNeil Jr.

Donald G. McNeil Jr.

What may be the most effective way to stop huge surges in infections during a pandemic?

Ground the planes.

Just do it. Tell the airlines: “No. You’re not booking hundreds of extra flights to Florida this week.”

I wish I’d written this a month ago, because now it’s too late to stop the new crisis that spring break may hand us.

Last Thanksgiving, I actually did write a note suggesting this to the editors of The New York Times editorial page. It was deemed a bit crazy.

I don’t think it is. Taking charge of air travel and throttling it back in places would be easy for the White House. It would almost undoubtedly be effective, even though it has not been tried in the United States.

We know from bitter experience that air travel provokes surges.

Late last November, we saw a surge of cases clearly linked to Thanksgiving travel. In December and January, we saw a second surge linked to Christmas travel.

From The New York Times Coronavirus Tracker

From The New York Times Coronavirus Tracker

Now we’re looking at another.

“We just do not want have a rapid uptick in cases — we are behind the 8-ball when that happens,” Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said this week. “Now is not the time to travel.”

Plane travel has two dangers: First, it exposes hundreds of people to each other in close quarters. Even when mask discipline is rigidly enforced inside the planes, it falls apart in long waiting lines, airport restaurants, buses to rental car lots, hotel lobbies and so on.

Second, it obligates strangers from different viral networks to swap their exhaled breath with each other (more on this later.)

A surge linked to spring break travel is bad news for our vaccine efforts. Even if cases do not surge nationwide, the criss-crossing of viral networks in Florida will almost inevitably move new variants — notably the South African one — to places where it was not seen before.

Last year’s spring break almost certainly spread the virus. Although that cannot be seen in the virus tracker above because we had so little PCR testing back then, cases increased in the chilly East Coast and Upper Midwest cities from which spring break partiers head to the coasts of Florida, Georgia and South Carolina.

(Like swallows and monarch butterflies, students seeking warm weather stick to certain flyways. Cellphone data from last year showed that almost none of them boarded flights to Florida from the Great Plains, the Rockies, or the Far West. The funnel down to southern beaches begins in a wide cone of snowy northern cities stretching from Boston to Chicago.)

The country then had very little testing capacity to prove the cellphone data accurate. Also, almost no genetic sequencing was being done. Therefore, it was impossible to tell if, for example, a variant strain had ricocheted from New York down to Florida and back up to Detroit.

(We tend to focus on strains with dangerous mutations, like those on the spike protein. But sequencing can pick up even minor blips anywhere in the genome that are useful for tracking viral migration.)

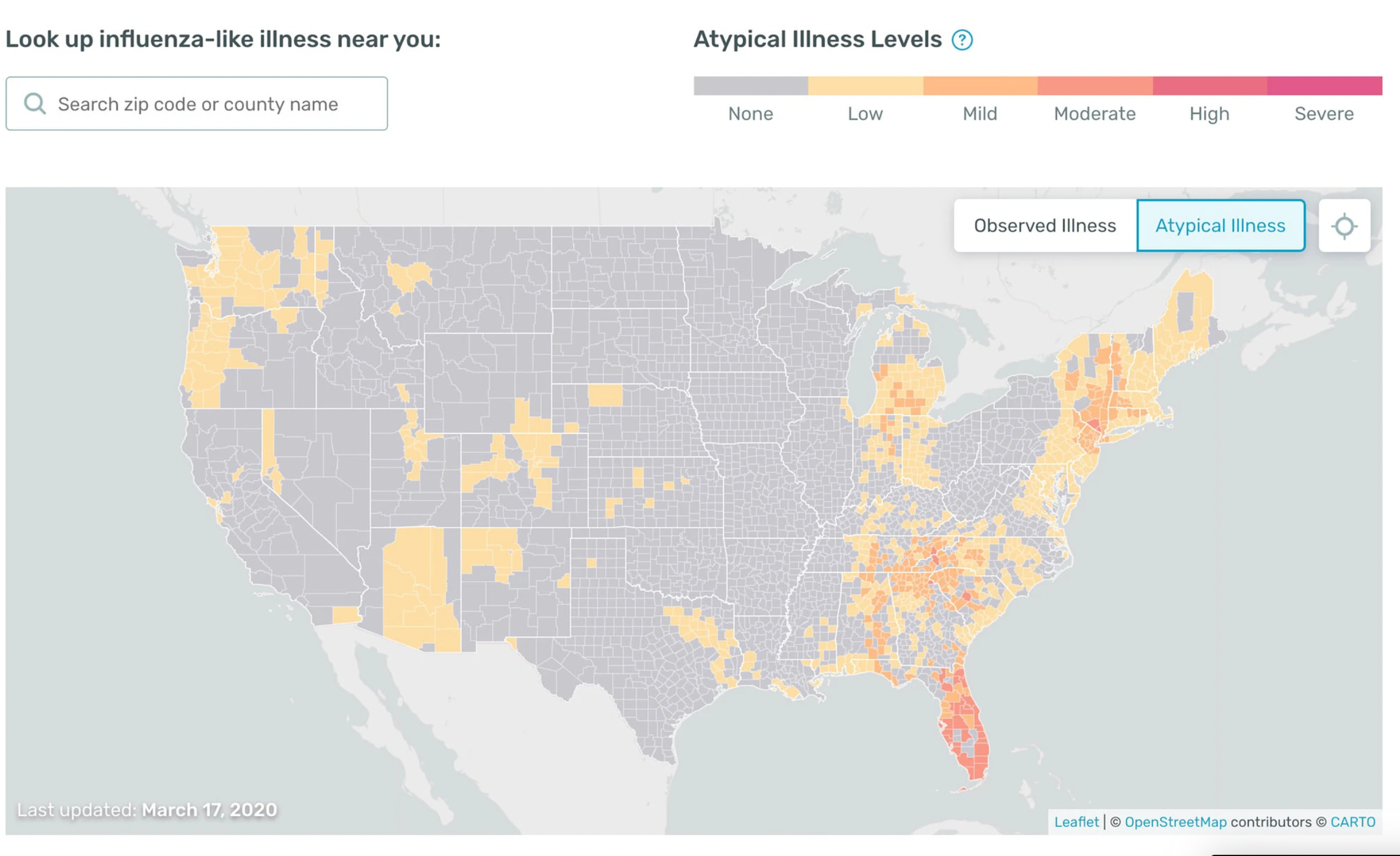

There was, however, strong evidence of such surges on the maps put out by Kinsa Health, a company that compiles data from millions of web-linked thermometers.

Even before PCR tests were widely available last spring, south Florida was showing up bright red on Kinsa’s maps, meaning that it had many fevers that were not explained by the fading flu season. So were several of the northern cities at the top end of the funnel. (Kinsa data was also some of the first evidence that social distancing and closing bars and restaurants worked: cities that took those measures very rapidly “cooled off” on the maps.)

In January, 2020, to stop the spread of the virus from Wuhan, the government in Beijing stopped all travel out of that city and Hubei province around it: planes, trains, buses, cars, everything. It worked remarkably well. (Not well enough to stop the pandemic, of course, but it contained it within China and the few countries that have imitated China’s travel restrictions, such as New Zealand, have done remarkably well.)

The White House could limit road travel — any vehicle crossing a state line amounts to interstate commerce. But that would massively inconvenience millions of uninfected Americans.

On the other hand, regulating airline travel is easy. The Federal Aviation Administration approves all flight plans and employs the nation’s air traffic controllers. The White House could rule that some routes at some times are just too epidemiologically unsafe to add flights to.

Spring break is a good candidate for such a ruling. We know that mass gatherings, like last August’s Sturgis motorcycle rally, are dangerous. (There was widespread disagreement over a mathematical model that concluded that the rally led to 250,000 cases, but careful epidemiological work later left no doubt that it triggered an explosion of cases in the Dakotas and other nearby states that had previously been spared.)

The danger in Florida is not on the beaches, just as the danger in Sturgis was never in the crowded parking lots that kept appearing on TV news drone shots. The danger is in the bars, indoor concerts and other enclosed spaces where one unmasked person with a big load of virus in his nose and throat could infect 50 others.

Yes, the airlines will scream if the FAA constricts those routes. Yes, the governor of Florida will scream. Yes, restaurant owners from Myrtle Beach to Miami will scream.

Too bad. We should consider it anyway, and perhaps compensate them.

Why?

For the nation’s sake. Some variants are looking more and more dangerous. Fast as we’re going, we are still not vaccinating fast enough. And if the South African variant or another equally dangerous one spreads far enough, all the vaccination we’ve done till now, at great expense and with huge drama, could soon be for naught.

Evidence is growing that that variant, which is also known as B.1.351 or 501Y.V2, can at least partially defeat the vaccines now approved in the United States and Europe.

The data is scant but scary.

A lab study done in February by scientists from Columbia University and the National Institutes of Health tested the virus then dominant in the United States (D614G, sometimes called the “Italian strain”), the British B.1.117 strain and the South African strain. They let each virus loose in a batch of human cells into which they had dripped various substances they hoped would block it: blood serum from people who had recovered from Covid (“convalescent plasma”), blood serum from people vaccinated with the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, and a dozen different monoclonal antibodies, including the three then being manufactured in bulk by Regeneron and Eli Lilly.

The results were not pretty. They showed that all the interventions were roughly equally effective against the British variant as against the circulating D614G strain. But many of them did much worse against the South African one.

The activity of some antibodies wasn’t just “impaired.” It was described as “completely or markedly abolished” — in other words, useless.

If you are infected, and if you have an underlying problem, or if your oxygen saturation slips below 90 percent, your doctor is going to suggest you get infused with monoclonal antibodies. I know a couple of people who have faced this worry just in the last two weeks. One friend’s lungs did start to go south; she got the infusion and recovered rapidly (as happened to President Trump in October.) Had she had the South African variant, she might be hospitalized now.

Real-world studies are confirming the fears raised by that impressive lab work. One study done in South Africa and published in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine is only about 10 percent effective against preventing infection by the South African strain.

Think of that: 95 percent effectiveness for some vaccines against the common strain versus 10 percent for this one versus this strain. Yes, vaccines are much better at preventing death than they are at preventing infection, but when efficacy against infection drops that much, you cannot feel safe.

A small study from Israel published in Cell Host and Microbe suggests that even the Pfizer vaccine gives only partial protection against the South African strain.

The spread of the South African variant — or the emergence of an equally dangerous American one — could potentially be bad news for all Americans, including us older vaccinated ones.

Why is that increasingly likely? Because in the last 40 years, two earth-shaking changes have taken place in virology: H.I.V. treatment and cancer therapy. Lifesaving as they are, they have blessed the earth with an army of innocent and unwitting petri dishes for new viral variants.

Previously, in the first billion or so years in the life of viruses, a virus had two evolutionary routes available: Kill your host and die out, or prosper by letting your host live to infect others. One theory as to how we got our immensely complex set of genes is that some viruses became so harmless and familiar that they were absorbed into our DNA because they helped perform other useful cellular functions, such as converting oxygen to energy.

In the past, the overall tendency of viruses — including the 1918 flu, which slowly evolved into the H1N1 seasonal flu — has been to become less dangerous. It’s Darwinian: a very lethal virus is driving fast down a dead-end street; its host crashes before it can infect others. A milder strain that lets its host go to a bar or to choir practice finds a multitude of new hosts. Nicer variants ultimately outcompete their nastier cousins, although there can be niches along the way in which nastier ones emerge and prosper.

We are creating such niches. We are learning that people with compromised immune systems — people who once would have died — may help drive the creation of new variants.

The most convincing case was that of a British man in his 70’s with Covid who died after 102 days of treatment, mostly in a Cambridge University hospital. Because he had been on immunosuppressive treatment for lymphoma, his immune system was barely functioning. Doctors struggling to keep him alive plied him with remdesivir and several rounds of convalescent plasma.

Meanwhile, they kept sequencing the different viral variants he had. Each time they introduced a new treatment, new variants would appear in his blood with mutations that helped them survive the new assault. The mutations piled up, making his virus more and more lethal.

There is no evidence that this suffering gentleman personally infected anyone. But the virus is now circulating among millions of people with partially suppressed immune systems.

This is pure speculation, but it may not be a coincidence that Covid variants have arisen in countries like Britain and the U.S. with many citizens on cancer treatment or, like South Africa and Brazil, with widespread H.I.V. epidemics. I know from my own reporting that drug shortages in rural South Africa can leave H.I.V. patients only partially protected for weeks at a time. I assume that Brazil has similar problems.

The South African variant has now been found in small clusters in 25 American states — largely in the same pattern we saw with the original virus as spring faded into summer last year: mostly in the Northeast and the Deep South.

We would be smart to do as much as we can to freeze it in place.

Which means keeping networks apart. Normally, viruses tend to stay within networks of people.

We know this from many diseases, including H.I.V. — it can enter a country like Kenya, Thailand or the United States and smolder along for a while at a low level, undetected. Then, suddenly, when it hits a network where there is lots of unprotected sex or lots of sharing of contaminated needles, it can explode to infect the majority of those in that network. Famous studies of sex workers in Nairobi, drug injectors in Bangkok and gay men in San Francisco have demonstrated that again and again.

But the virus often then stays largely within that network. It does not necessarily spread to the rest of the population.

We see that with other viruses too — even ones that are far easier to transmit than H.I.V. The more insular the community, the most likely the virus is to stay contained. The last polio outbreak in the United States, in 1979, stayed largely within the Amish communities who had imported it from a global Mennonite convocation. The 2019 measles outbreak in New York City and its suburbs stayed almost entirely within the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community even as travelled back and forth between Brooklyn and other ultra-Orthodox communities in Israel, Britain and Ukraine.

Even SARS-CoV-2, despite being globally disseminated, and for which there was no vaccine until fairly recently, has spread through networks.

It is well-known that, in the first wave in New York City in the spring of 2020, the virus hit some communities especially hard, including black and Hispanic New Yorkers with front-line jobs. But it also hit Hasidic Jews, who had just celebrated Purim together. It hit Filipino nurses, who often worked in hospitals and nursing homes short on personal protective gear. It hit ambulance crews of all races who had to transport the sick. It hit transit workers of all races. And so on.

Outside of New York City that spring, it hit almost nowhere in the Mountain States — except in one unique type of setting: skiers and ski resort workers in Sun Valley, Idaho; Vail, Colorado and a dozen other Rocky Mountain ski towns fell sick and died. Presumably, that was the virus moving from the Italian and Austrian Alps to America using wealthy skiers as vectors.

Normally, networks don’t cross very much. People tend to hang out with like-minded people. Hasidic Jews attend services with Hasidic Jews, ambulance drivers eat lunch with other ambulance drivers, skiers drink mulled wine with other skiers, sorority sisters and fraternity brothers attend the same parties, and so on.

But mass gatherings send diseases leaping from one network to another. Historically, the hajj to Mecca has spread many epidemics, including cholera and polio. A Catholic youth conference in Australia in July 2008 — high flu season in Australia — remixed influenza strains all over the world.

When we cancel basketball games and cruise ship sailings, we recognize that mass gatherings are dangerous. But those are fairly localized.

We need to recognize that mass gatherings on a national scale are even more dangerous. Events like spring break are just the kinds of opportunities that viruses seek out. We would be smart to get ahead of them however we can. Cutting off or tightly constraining air travel at crucial moments could be one way to accomplish that. Hard as it would be on some parts of the economy, a failure of our vaccines would be far harder on our nascent recovery and send us rapidly backwards.