Emitting greenhouse gases in WA? Here’s who will need to pay up to pollute

Blue and orange flames flicker and whir within five massive natural gas-fired boilers, visible only through hatches where coal used to be shoveled.

They burn up to 90,000 therms a day to feed a 7.5-mile network of pipes that provide steam, hot water and emergency electricity for the campus, including a hospital and laboratories. On a cold winter day, the belly of the University of Washington’s steam plant is sweltering.

Here, near Lake Washington’s shore, the university has burned fossil fuels since the 1890s. But this year, it comes at a much steeper cost.

Washington state last month launched its complex carbon-pricing scheme, in which most of the state’s biggest emitters of climate-warming greenhouse gases can buy and sell carbon allowances — permits to pollute. On Tuesday, the allowances for the first time will go up for sale in an online auction.

This new market is only the second of its kind in the United States and is a major test of state lawmakers’ grand ambitions to rein in climate pollution. Even before the first bids have been placed, it has unleashed a political tug of war over potential impacts for consumers.

If everything goes as planned, the state will be mostly carbon-free by 2050. That’s a more accelerated timeline than in California, where emissions reduction targets remain somewhat elusive a decade after its carbon-pricing program began.

The University of Washington, with its natural-gas boilers, is just one of the dozens of entities regulated under the state’s program.

The campus produced nearly 90,000 metric tons of climate-warming greenhouse gases in 2021. UW anticipates it will pay up to $5.2 million a year for its emission allowances.

Yet it’s still unclear exactly who has to pay. And not all polluters are treated the same. Some of Washington’s biggest emitters will have to start paying for their emissions, but many others — like oil refineries, lumber mills and dairy companies — get free pollution permits to start.

Businesses are still learning how to use updated emissions reporting systems. And oil companies are already this year baking in costs from the program to pass down the supply chain, which may increase gas prices at the pump.

Washington lawmakers say they’ve learned from California’s mistakes, but some climate economists and scientists say the ambitious plan may fall short of meaningful reductions in pollution.

A true accounting of how Washington might fare against the state’s biggest polluters won’t be known for years. But the program’s launch suggests a tough fight ahead.

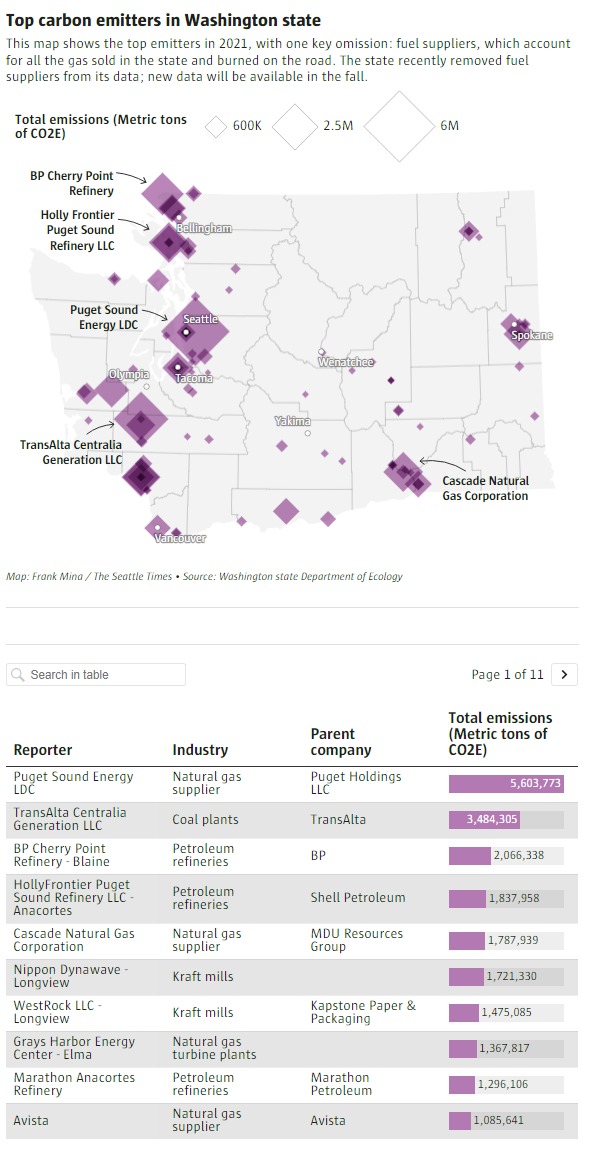

Puget Sound Energy, an investor-owned utility responsible for providing electricity and heat for some 1.3 million homes and businesses, was the top emitter in 2021. The utility reported more than 5.6 million metric tons of emissions from the gas it supplies to customers, and nearly 3 million metric tons from its seven natural gas-fired power plants.

Private, state-regulated utilities like PSE blow the University of Washington’s emissions out of the water, but unlike the school, PSE doesn’t have to pay into the state’s carbon-pricing program for another three years.

Another top climate-polluter was Nippon Dynawave, a company that produces bleached paperboard to make cartons and cups for milk, juice, coffee and sake in a mill on the shores of the Columbia River in Longview. Its emissions topped 1.7 million metric tons in 2021. But it, too, won’t have to pay right away.

While the program was being envisioned under the state’s 2021 Climate Commitment Act, the company and other pulp and paper mill trade associations were among those who lobbied for free allowances. They feared jobs and business could leak to other states.

Under the law, some businesses susceptible to fluctuations of global and regional markets will receive all of their allowances for free until 2026 and gradually get less over time.

BP operates the state’s largest oil refinery, near Lummi Nation. It processes about 225,000 barrels of petroleum per day, and recently got the OK from the Army Corps of Engineers to double the volume of crude oil it brings in.

The oil giant’s refinery pumped out over 2 million metric tons of greenhouse gases in 2021, landing it in the state’s top five.

A company spokesperson said BP remains supportive of the state’s new program.

In the past, BP has publicly supported policies seeking to reduce climate-warming emissions. But the company and its trade group representatives have sometimes lobbied for special treatment that undermined those same efforts.

BP in February announced it would join Shell in slowing its transition to clean energy, investing an additional $8 billion in fossil fuels. The announcement came on the heels of a report detailing the company’s record profits — nearly $30 billion in 2022.

The oil giant also won’t have to pay for its refinery’s emissions until 2026.

Emissions from Washington’s petroleum refineries totaled more than 6 million metric tons in 2021, equivalent to burning about 30,000 rail cars full of coal.

The suppliers, like BP, Shell and Phillips 66, are often owned by the same companies that do the refining. And they, too, are responsible under the state’s program to pay for emissions coming from Washingtonians’ tailpipes.

Suppliers made up more than 25 million metric tons of emissions in 2020, or about 46% of all emissions that year, according to state data.

Almost 6.2 million allowances will go up for auction on Tuesday. They start at $22.20 per ton of emissions. Emitters, either mandatory participants or those who opt-in, as well as investors hoping to resell the allowances for a profit, can participate.

Over the next two years, these auctions are projected to generate about $1.7 billion. The Legislature will decide how it is spent on projects intended to further reduce the state’s carbon emissions.

It is yet to be seen how much of polluting businesses’ new compliance expenses will fall on consumers.

Washington state failed to pass a ballot initiative that would’ve put a tax on carbon in 2016, and a similar fee in 2018. But with the Climate Commitment Act and its carbon-pricing scheme, lawmakers finally broke through.

Now a growing chorus of fuel distributors, who buy fuel and deliver it to your neighborhood gas station or to your home’s oil tank, oppose the state’s new program, saying suppliers are instead passing the cost down the supply chain.

The Oil Price Information Service (OPIS), a Dow Jones company, assessed how the state’s carbon-pricing program is affecting fuel prices. According to the company’s analysis, compliance costs for gasoline and diesel could reach $1.2 billion this year.

The average retail price for gasoline at the pump barely budged at the beginning of the year, according to a Seattle Times analysis of pump prices compiled by AAA. But since late January, the difference between Washington’s retail prices and the national average has increased by nearly 20 cents a gallon.

There’s no industry standard for how fuel suppliers manage compliance costs, said Lisa Street, head of Climate & Carbon Markets at OPIS. One supplier may pass the cost along as a line item in wholesale fuel invoices, while others may choose to include the costs in their total fuel prices.

In an early January interview with members of the Washington Independent Energy Distributors, a trade association representing businesses that sell petroleum products, some shared concerns over the state’s new program.

Steve Snider, owner of Snider Energy Company, a small fuel distributor, is worried about how his business will survive the spike in prices from suppliers.

Fuel distributors fill their tanker trucks at big oil suppliers like BP. They deliver the fuel to gas stations, or directly to homes that use oil for heat. Others may have contracts to fuel up trucking companies’ fleets that deliver produce to grocery stores, or cement to construction sites.

While the state’s carbon-pricing scheme is “not a tax,” according to the Department of Ecology, some fuel suppliers appear to be treating it that way.

Todd Shaw, vice president of Jubitz Corporation, a fuel distributor that trucks fuel between customers in Washington and Oregon, said the lack of clarity around how the law would affect their business has “caused some real heartburn.”

Fuel distributors say the oil companies didn’t know the cost of the new carbon-pricing program on their business, so in the meantime, “they’re just throwing darts and trying to make sure they don’t lose out in a month or so,” said Steve Clark, president of Genesee Energy, a heating fuel distributor in the Seattle area.

“They’re passing this huge price increase down to us,” he said.

Even farmers and ranchers, whose fuel use is exempt from the state’s program, are reporting rising costs this year.

The Washington Farm Bureau said in a statement that the Department of Ecology had not been clear enough in its rule-making to ensure the fuel exemption.

The bureau “began receiving feedback from farmers and interested parties that the industry was not receiving the entire exemption outlined in the new law,” the bureau said.

Claire Boyte-White, an Ecology spokesperson, said companies are preemptively incorporating what they anticipate their costs to be, and those estimates seem to be “pretty inflated.”

Efforts to sway public opinion are underway. Above some gas pumps, advertising boards — usually promoting premium fuels or an attached car wash — now warn of rising fuel prices.

“Tax on a gallon of gas is projected to increase $.46 a gallon next year and $.57 for diesel,” reads one sponsored by the Washington Policy Center, a conservative think tank.

The center has repeatedly described the state’s new program as a “tax” and circulated petitions calling for its repeal.

Washington’s carbon-pricing program largely relies on the road map drawn up by lawmakers in California a decade ago. The Golden State met its 2020 emissions target four years early, and lawmakers say the program has proved that economies can grow while pollution declines.

But local air pollution has been on the rise and carbon offsets have proved largely ineffective as the program has rolled out.

California’s cap-and-trade program is framed by three emission reduction targets: to 1990 levels by 2020, to 48% below 1990 levels by 2030, and to 85% below 1990 levels by 2045.

Many polluting businesses now have a surplus of saved allowances and won’t necessarily need to cut emissions. Policy analysts and energy economists say some polluting companies might not have to change much at all.

State officials last year assessed California’s climate change programs and called for more incentives for private investment in low- and zero-carbon fuels, electrifying buildings and zero-emissions cars.

“I’m glad we led in California,” said California state Sen. Josh Becker, who helped craft his state’s climate policy. “Washington state had years to kind of learn — they did very seriously look at our system and learn from it and improve upon it.”

Washington’s program is about one-fifth of the size of California’s, which has about 500 businesses participating in the program. California generated more than $2 billion from the program in 2020.

Washington has stricter rules around the allocation of free allowances. In California, all industrial facilities receive free allowances.

In both programs, allowances beyond what’s needed to pay for the company’s emissions can be “banked” and don’t have expiration dates.

A 2022 report found that companies participating in California’s program have bought and saved 321 million of these allowances, which could make it difficult for the state to force these companies to lower their emissions to meet the state’s 2030 goals.

“Carbon prices in California for a long time were basically at the floor,” said Mark Trexler, a climate policy analyst and former offset project developer. “And it’s only very recently that they’ve sort of gone up to a potentially, eventually meaningful level.”

Those who have paid the most immediate price for the program’s shortcomings are those who live near major emitters and have seen worsening air quality, the LA Times reported. These are similar concerns that have been echoed by Washington’s environmental justice leaders.

If a Washington business buys an offset — a forest offset or environmental service project — one less emission allowance will be available at auction. Polluters can cover up to 8% of their emissions to start.

Comparatively, in California, offsets may be used in addition to pollution allowances.

Across the board, there is little effort to ensure offsets are actually sequestering carbon as intended.

“What we’ve done with offsets is we’ve set up a system where there is no prosecutor,” Trexler said. “So there’s only a defense attorney presenting the case to the jury. And the jury has a financial interest in approving the projects, in many cases.”

“The incentive structure is that everyone wants to reduce compliance costs,” he said. “No one really wants to maximize environmental integrity. And those two things cannot be maximized simultaneously.”

Washington’s legislation tasks Ecology with identifying communities that are overburdened by air pollution and targeting the significant sources of this pollution. The goal is to ensure air pollution targets are being met, and potentially impose stricter guidelines on businesses covered within the program near front-line communities.

Polluters will have to together reduce statewide emissions by more than 6% each year to meet the state’s 2030 goals, and have a long road to carbon neutrality.

Washington state’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 reached their highest level since 2007: 102 million metric tons. It was a 7% increase from 2018, and 9% higher than emission targets set by the state Legislature for 2020.

The results of the first auction, or how much money it raises, will be released in early March, and polluters’ allowances aren’t due back to the state until fall 2024.

In the meantime, some polluters are mapping out their own path to net-zero.

A glass jar of coal sits on a desk as old as the university in UW’s makeshift power-plant museum.

The combustible black hunks were pulled from the grates of the plant in 1988. That’s when the university switched from coal to natural gas “to be good neighbors,” said Mark Kirschenbaum, assistant director of campus utilities.

In the same room are poster boards and papers that illustrate the university’s path away from fossil fuels. Some suggest opportunities for recycling heat from the city’s sewer system, or cool water from Lake Washington.

Now, the university is preparing to switch to water-source heat pumps, an efficient cooling and heating technology that uses electricity. The university expects its transition could cost more than $500 million.

Seattle Times reporters Hal Bernton and Manuel Villa contributed to this report.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misstated Nippon Dynawave’s parent company.