ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2024:3734

Government liability; 8 ECHR; Aviation Act

1.1. In these proceedings, RBV claims that the District Court should rule that the State has acted unlawfully by exposing a disproportionate number of people to serious nuisance and sleep disturbance caused by air traffic to and from Schiphol, including by assuming that the permissible levels of noise exposure are too high in regulations. RBV argues that the State should base itself on the noise standards set by the World Health Organization and/or on standards that offer a level of protection equivalent to the Airport Traffic Decree of 2004. RBV also believes that the State does not offer citizens practical and effective legal protection against serious noise nuisance and sleep disturbance as a result of air traffic to and from Schiphol. RBV therefore also claims that the court orders the State to put an end to this unlawful situation, among other things by reducing the number of flight movements to and from Schiphol and by providing practical and effective legal protection.

1.2. The State puts forward a defence. The State believes that it is up to the legislator, and not the courts, to find a fair balance between the interests of residents, Schiphol, airlines, people who work at or around Schiphol and Dutch society as a whole. In addition, the State points out that many measures have already been taken to control noise nuisance, and that new measures are in the making.

1.3. In short, the court concludes that the State is acting unlawfully by failing to enforce the applicable legal framework for noise nuisance around Schiphol for almost a decade and a half, and by basing the policy that has been made and implemented since then on measuring points that have been clear since 2005 do not provide a complete picture of (the distribution and severity of) the noise nuisance. Due to the lack of adequate and effectively enforced standards, people who experience nuisance from Schiphol have also lacked effective legal protection for years. In addition, in the State’s actions, the ‘hub function’ and the growth of Schiphol have always been put first and are first guaranteed; Only then did they look at how the interests of local residents and others could be met – without assessing whether the compensation that was still possible did sufficient justice to those interests. This way of balancing interests does not meet the requirements of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR) in cases such as this.

1.4. The court therefore partially grants the requested declaratory judgment. The court can only grant part of the orders sought by RBV. It is up to the legislator, after a correct weighing of all interests involved in aviation, to draw up concrete laws and regulations. The World Health Organization’s standards are not binding, so the court cannot impose them. However, the court orders the State to enforce the applicable legislation. Furthermore, the court orders that the State create a form of practical and effective legal protection that is accessible to all seriously inconvenienced and sleep-disturbed persons, including those who live outside the current noise contours. Within this legal protection, the interests of the individual must be sufficiently individualised and motivated.

Rechtspraak.nl OGR-Updates.nl 2024-0035

Sdu News Environmental Law 2024/86

Pronunciation

DISTRICT COURT of The Hague

Team Trade

Case number: C/09/632625 / HA ZA 22-610

Judgment of 20 March 2024

In the case of

FOUNDATION FOR THE RIGHT TO PROTECTION AGAINST AIRCRAFT NUISANCE,

in Aalsmeer,

claimant,

hereinafter referred to as RBV,

Lawyers: mrs. C. Samkalden and E. ten Vergert in Amsterdam,

against

THE STATE OF THE NETHERLANDS (Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management),

in The Hague,

defendant,

hereinafter referred to as the State,

Lawyers: mrs. E.H.P. Brans and M.T. Peters in The Hague.

1Summary

1.1.In these proceedings, RBV claims that the District Court should rule that the State has acted unlawfully by exposing a disproportionate number of people to serious nuisance and sleep disturbance caused by air traffic to and from Schiphol, including by assuming that the permissible levels of noise exposure are too high in regulations. RBV argues that the State should base itself on the noise standards set by the World Health Organization and/or on standards that offer a level of protection equivalent to the Airport Traffic Decree of 2004. RBV also believes that the State does not offer citizens practical and effective legal protection against serious noise nuisance and sleep disturbance as a result of air traffic to and from Schiphol. RBV therefore also claims that the court orders the State to put an end to this unlawful situation, among other things by reducing the number of flight movements to and from Schiphol and by providing practical and effective legal protection.

1.2.The State puts forward a defence. The State believes that it is up to the legislator, and not the courts, to find a fair balance between the interests of residents, Schiphol, airlines, people who work at or around Schiphol and Dutch society as a whole. In addition, the State points out that many measures have already been taken to control noise nuisance, and that new measures are in the making.

1.3.In short, the court came to the conclusion that the State was acting unlawfully by not enforcing the applicable legal framework for noise nuisance around Schiphol for almost a decade and a half and by basing the policy that has been made and implemented since then on measuring points that have been clear since 2005 do not provide a complete picture of (the distribution and severity of) noise nuisance. Due to the lack of adequate and effectively enforced standards, people who experience nuisance from Schiphol have also lacked effective legal protection for years. In addition, in the State’s actions, the ‘hub function’ and the growth of Schiphol have always been put first and are first guaranteed; Only then did they look at how the interests of local residents and others could be met – without assessing whether the compensation that was still possible did sufficient justice to those interests. This way of balancing interests does not meet the requirements of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR) in cases such as this.

1.4.The court therefore partially granted the requested declaratory judgment. The court can only grant part of the orders sought by RBV. It is up to the legislator, after a correct weighing of all interests involved in aviation, to draw up concrete laws and regulations. The World Health Organization’s standards are not binding, so the court cannot impose them. However, the court orders the State to enforce the applicable legislation. Furthermore, the court orders that the State create a form of practical and effective legal protection that is accessible to all seriously inconvenienced and sleep-disturbed persons, including those who live outside the current noise contours. Within this legal protection, the interests of the individual must be sufficiently individualised and motivated.

2Table of contents

2.1.In paragraph 3 of this judgment, the court will first describe which documents were added to the case file after the interlocutory judgment of 15 November 2023, in which it was decided that RBV is admissible in its claims, and how the proceedings proceeded afterwards. In paragraph 4 she describes the facts on which the court based its assessment; in paragraph 5 it briefly describes what RBV has claimed and what the State’s defence entails.

2.2.The essence of the judgment is set out in paragraph 6. In that paragraph, the court first describes which legal framework applies to this case, and then assesses the claims on the basis of that. A summary of the decision can be found in section 7.

3The procedure

3.1.Following the interlocutory judgment of 15 November 2023, the following documents were added to the case file:

– RBV’s deed of submission of exhibits 101-130, received on 3 January 2024;

– the State’s document of submission of exhibits 39-61, received on 3 January 2024;

– the State’s document of submission of exhibits 62-73, received on 11 January 2024;

– RBV’s deed of submission of exhibits 131-135, received on 18 January 2024;

– the deed of submission of production 136 of RBV, received on 22 January 2024;

– the State’s document of submission of exhibits 73-77, received on 22 January 2024; and

– RBV’s deed of submission of exhibits 137-138, received on 25 January 2024.

3.2.The hearing took place on 30 January 2024. The parties appeared, assisted by their lawyers. The lawyers gave an oral explanation on the basis of speaking notes, which were added to the case file. The parties answered questions from the court and were able to respond to each other. The Registrar took notes of what was discussed at the hearing. Those notes have been added to the Registry’s file.

3.3.Finally, the date on which that judgment is to be delivered has been fixed.

4The Facts

Noise exposure and its effects

Noise exposure

4.1.In the Aviation Act (Wlv) the term noise exposure1 appears. This term is not defined in the law itself; it has been taken over from the Environmental Noise Directive, which can be discussed in 4.15. For the purposes of this judgment, the term ‘noise pollution caused by air traffic’ means the noise produced by all air traffic to and from Schiphol together during a year. Under the Wlv and the Environmental Noise Directive, various factors must be taken into account when calculating the noise exposure, such as the number of flight movements and their distribution over the day, the flight paths, the use of the runways and the aircraft types with associated performance and noise data.

4.2.In the Netherlands, until 2007, the noise indicator Ke2 was used for the noise exposure during the entire day and LAeq3 for the noise exposure between 23:00 and 6:00. In 2007, these noise indicators were finally completely replaced by the European noise indicators Lden4 and Lnight 5, which are based on the average noise exposure between 23:00 and 07:00. 6

4.3.Based on calculations of the noise exposure of air traffic at various points around an airport, a noise (exposure) contour can be determined. This is a line on a map that connects points with the same noise exposure from the same type of noise source. In the area (the zone) within the contour, the noise exposure is higher; Outside of that, the noise exposure is lower. Schiphol’s noise contours are redefined annually because the noise exposure varies due to weather conditions, changes in flight paths, the number of aircraft movements and the types of aircraft used.

Noise pollution, sleep disturbance and other health effects

4.4.Noise nuisance7 and sleep disturbance are effects that people experience above a certain noise level caused by air traffic. In addition to the degree of noise exposure to which one is exposed, other (non-equivalent) acoustic factors also determine the noise nuisance or sleep disturbance experienced. This includes the frequency and times at which aircraft fly over, the number of aircraft flying over, the number of passes above a certain noise threshold and the time between passages. In addition, factors that are unrelated to the physical noise also play a role, the so-called non-acoustic nuisance factors. These factors originate from situational, personal, contextual or social circumstances, such as the attractiveness of the living environment, the (un)predictability of the sound, the fear of the noise source and the possibility of addressing the noise problem.

4.5.The degree of noise or sleep disturbance experienced by a group of people in a given location is calculated using exposure-response (BR) relationships, also known as dose-response relationships. These relationships are partly based on questionnaire surveys8 that were conducted within the group and describe the proportion of people who are seriously bothered or sleep disturbed ‘on average’ at a certain noise exposure. 9 This is expressed as a percentage. BR relationships are not universal and are subject to change. The nuisance experienced may vary over time and according to location. There are also differences in the research methods used to derive BR relationships and the circumstances that are taken into account (e.g. non-acoustic nuisance factors).

4.6.In the noise indicator Ke, the BR relationships were calculated in a different way than in the noise indicators Lden and Lnight; the percentage of the number of seriously hindered persons based on the BR relationship for Lden is higher than the percentage based on the BR relationship for Ke.

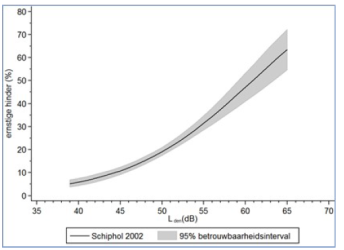

4.7.Since 2006, the calculation of the noise nuisance effects of air traffic to and from Schiphol in the context of the equivalence criteria (see 4.21 and 4.22), which will be discussed below (see 4.21 and 4.22), has been based on the Health Evaluation carried out by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) at Schiphol GES-2002; see footnote 8). The BR relationship used to determine the number of people who are seriously affected by noise is shown in Figure10 below:

The influence of non-acoustic factors has not been taken into account in the BR relationships established on the basis of the GES-2002. 11 In 2023, RIVM concluded, based on research data from 2020, that the GES-2002 is no longer a good description of the current BR relationship between aircraft noise and nuisance and sleep disturbance around Schiphol. A 12

4.8.Exposure to environmental noise, such as aircraft noise, can have other negative effects on health in addition to nuisance and sleep disturbance. These include high blood pressure, metabolic diseases, hearing loss and cognitive problems. These negative health effects are largely the result of the (physical and psychological) stress that noise can cause. 13 In addition, discomfort and sleep disturbance can in turn lead to other health problems, such as cardiovascular disease. 14

The development of air traffic to and from Schiphol

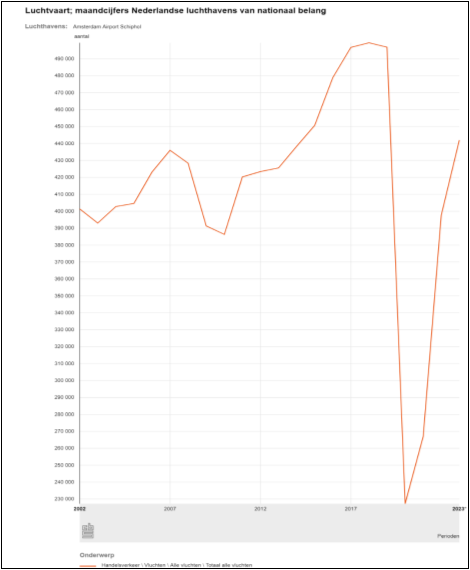

4.9.Since 2003, Schiphol has had five long runways: the Aalsmeerbaan Runway, the Buitenveldertbaan Runway, the Kaagbaan Runway, the Polderbaan Runway and the Zwanenburgbaan Runway. 15 Since the entry into operation of the five-runway system (more on this below) and in particular from 2010 onwards, the number of commercial aircraft movements to and from Schiphol has grown considerably, leaving aside the Covid-19 period, with a peak in the period 2017-2019. During that period, there were almost 500,000 aircraft movements per year.

The legal framework

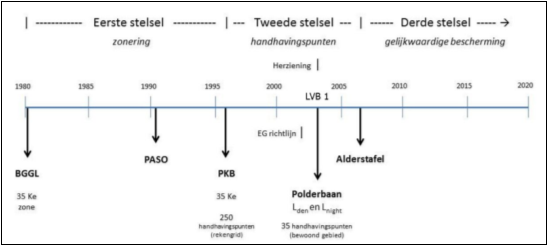

4.10.Over the years, the noise pollution caused by air traffic to and from Schiphol has been regulated in various ways. The timeline17 below shows the developments in the successive enforcement regimes from 1980 to 2020. These developments will be discussed below.

Noise zoning

4.11.In the years 1980 to 1995, when Schiphol still had four runways, the noise exposure from air traffic to and from Schiphol was indicatively limited by a noise zoning system based on Ke and LAeq zones. Air traffic was not allowed to cause noise pollution that was higher than the noise zones indicated. The limit value for the maximum permissible noise exposure in Ke zones was 35 Ke18 and for the LAeq zones 26 dB(A)19. 20 Within these zone boundaries (contours), the noise exposure could be higher.

The key planning decision for Schiphol and the surrounding area

4.12.On 22 December 1995, the Key Planning Decision for Schiphol and the Environment (hereinafter referred to as the PKB) was adopted. It summarises the principles, outlines and most important measures of the policy proposed by the government at the time with regard to the development of Schiphol and the surrounding area. The PKB had a double objective: to strengthen Schiphol’s mainportfunction21 and to improve the quality of the environment in the vicinity of Schiphol. 22 According to the government, the construction of a fifth runway (the current Polderbaan Runway) was the best alternative for achieving this dual objective. The starting point was that the quality of the living environment should not deteriorate as a result of the commissioning of the fifth runway and, with regard to noise, would be better than the level of protection that applied at the time when four runways were still in use. A 23

4.13.

The PKB includes indicative noise zones for the five-lane system, the 35 Ke zone and the 26 dB(A) LAeq zone. To enforce the 35 Ke zone, 250 enforcement points were used that were located at a maximum of 500 meters from the 35 Ke contour. 24 The government set itself the goal of reducing the number of dwellings within the 35 Ke zone from 15,100 in 1990 to 10,000 in the period after the fifth runway was put into use (in 2003). The housing stock of the year 1990 was used to determine this number. 25 This means that dwellings built after 1990 but within the 35 Ke contour are not included in the calculation of the number of dwellings within the contour.

In view of the intended growth in the number of aircraft movements due to the further development of Schiphol into a mainport, the plan to establish a larger noise zone – namely a reserved noise zone with a maximum of 12,600 homes based on the 1990 housing stock – met with criticism from the House of Representatives and was therefore removed from the PKB. A 26

4.14.In the Schiphol Aerodrome Designation, which was adopted shortly after the PKB, the noise zones referred to in 4.13 have been definitively determined. A 27

The Environmental Noise Directive

4.15.Since 18 July 2002, the Environmental Noise Directive28 has been applicable. The purpose of this Directive is to establish a common approach throughout the European Union to combat the harmful effects of exposure to environmental noise29 . To achieve this objective, noise indicators have been established to measure long-term exposure to environmental noise during the day and to measure sleep disturbances (Lden and Lnight). In addition, the Directive requires Member States to draw up noise maps and action plans for airports with more than 50,000 aircraft movements per year, in order to prevent and reduce nuisance and other harmful effects caused by noise pollution. It also includes measures aimed at implementing the national action plans and informing the public. It also provides the basis for developing (where necessary) EU measures to reduce noise from the main sources of noise, including aircraft.

4.16.The Environmental Noise Directive was implemented in Dutch law in 2004. 30 To that end, the Law on noise abatement and the Law on aviation and the Law on railways were amended.

The Aviation Act, the Schiphol Airport Classification Decree and the Schiphol Airport Traffic Decree

4.17.In 2003, a new chapter – Chapter 8 – was added to the Aviation Act (Wlv) that focuses on Schiphol. This chapter provides a basis for the introduction of the five-lane system and the introduction of new systems of limit values and of information and enforcement. The latter was related to the change in thinking about setting volume limits for air traffic at Schiphol Airport. The Explanatory Memorandum states the following:

At the time of the PKB, the safety and environmental limits were determined partly on the basis of a growth scenario drawn up by the government. In order to give these limits the necessary “hardness”, the growth scenario, in the form of volume ceilings, was also defined. In short, the current rationale is that a system of safety and environmental limits should not protect against the number of aircraft, passengers or tonnes of cargo, but against the consequences of the associated air traffic. Government policy should be primarily aimed at setting good and enforceable safety and environmental limits. The government must then create a regime in which the aviation sector, within the set limits, is given the space to develop its growth potential. In particular, it is the sector itself that is able to achieve an optimal result (e.g. through investments in the fleet or by improving flight procedures) – provided that the opportunity is given to do so. The sector has also expressed its desire to develop its own growth potential. In this approach, it is less appropriate for the government to set a growth scenario. It is the sector that indicates the potential that is seen; Based on this, the government can assess whether those expectations are and remain in line. A 31

4.18.It follows from Section 8.2 of the Wlv that further rules on the layout of the area at and around the airport and rules on air traffic to and from the airport are laid down in an airport classification decree (LIB) and an airport traffic decree (LVB) respectively. 32 For the purposes of the action as submitted, only the LVB is relevant.

4.19.The LVB is aimed at controlling the extent and distribution of the consequences of airport traffic with regard to the aspects of (external) safety, noise (nuisance), local air pollution and odour (nuisance). To this end, the LVB sets limit values for these aspects, among other things. 33 Protection against noise exposure includes, first of all, limit values for the total volume of noise exposure (TVG) over a whole day (24 hours; Lden) and during the night (23:00 and 07:00; Lnight). 34 In addition, there are limit values for noise exposure at certain enforcement points in or on the outskirts of residential areas near Schiphol. The limit values for the TVG serve to limit the total noise exposure caused by airport air traffic and are independent of the actual distribution of the noise exposure over the environment in a (use) year. 35 On the other hand, the limit values in the enforcement points are intended to control the distribution of noise pollution in the vicinity of Schiphol. 36 The limit values are based on forecasts about the (composition of the) fleet at Schiphol and the handling of traffic. This includes an estimate of the timetable (which aircraft types fly to which at what time of day) and the use of the runways and routes. It turns out that such a prediction often does not come true completely: the composition of the fleet is different, the runway use differs from what was assumed at the time, the actual timetable is different from what was predicted, etc. As a result, the noise exposure is distributed differently over the environment in practice than on the basis of the calculations. A 37

4.20.It follows from the explanatory memorandum that the LIB and the LVB must jointly ensure protection with regard to safety and noise. The LVB limits the consequences of airport air traffic (among other things) in terms of the external safety risk and noise exposure at certain points on the ground. The number of people affected by these consequences is limited by the building and use restrictions imposed by the LIB. A 38

4.21.The legislator considered that the level of protection offered by the first LIB, the first LVB and the new enforcement regime should be equivalent to that of the PKB. In order to achieve this,39 transitional articles have been included in the Act amending the Wlv, in which a number of concrete rules for a (on balance 40) equivalent transition from the old system (PKB) to the new system (LVB) have been formulated: the so-called equivalence criteria. 41 The noise limit values were set out in Article XII of the Law amending the Wlv:

- –the number of seriously inconvenienced persons within the 20 Ke contour to be calculated is a maximum of 45,000;

- –the number of people experiencing sleep disturbance42 within the 20 dB(A) LAeq contour to be calculated is up to 39,000;

- –the 35 Ke contour to be calculated includes a maximum of 10,000 dwellings; and

- –the 26 dB(A) LAeq contour to be calculated includes a maximum of 10,100 dwellings.

Those numbers were to be fixed in accordance with the manner in which they were fixed in the PKB. In addition, Article XII stipulates that the location of the 35 Ke contour is the starting point for the location of the enforcement points (mentioned in 4.19).

4.22.The system of equivalence criteria comprises three parameters that are important for determining the number of people who are seriously disturbed and sleep disturbed by aircraft noise, namely noise contours, housing stock and the aforementioned BR relationships (see 4.5 to 4.7).

4.22.1.Noise contours represent the noise situation in the area around or along a noise source. For aircraft noise, noise contours of the noise exposure around the airport in question are calculated and displayed. Noise contours are the result of the calculations based on the transfer model, the volume of air traffic and the data on aircraft noise emissions. 43 The consequence of changes in the noise contours is that there are also changes in the values of the parameters of the equivalence criteria. A 44

4.22.2.The numbers of dwellings used are influenced by the size of new construction or the demolition of dwellings in the areas considered. The concept of dwelling can also be redefined on the basis of changes in regulations. The consequence of changes in house numbers is that there are also changes in the values of the parameters of the equivalence criteria. A 45

4.22.3.Changes in the BR relationships also lead to changes in the values of the parameters of the equivalence criteria. A 46

4.23.The equivalence criteria served as a starting point for, among other things, the noise exposure limit values set out in the first LVB, expressed in the European noise indicators Lden and Lnight. The limit values set had to offer equal to or better protection than the level of protection laid down in the equivalence criteria (i.e. equal to or better than the criteria formulated in Article XII of the Act amending the Wlv). A 47

4.24.Subsequent decisions must also provide equivalent protection. 48 In the case of the LVB, this is laid down in paragraph 7 of Article 8.17 of the Wlv, which provides:

Each decree following the first Airport Traffic Decree provides a level of protection with regard to external safety, noise pollution and local air pollution, which for each of these aspects, determined on average on an annual basis, is on balance equivalent to or better than the level offered by the first decree.

Paragraph 4 of Section 8.7 of the Wlv contains a similar provision for the LIB.

4.25.In order to assess whether there is an equivalent or better level of protection, an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) must be drawn up when preparing (a material modification of) an LIB or LVB. In it, the environmental effects are mapped out on the basis of various scenarios. A scenario includes the number of aircraft movements, their distribution over take-offs and landings, the time of day, the types of aircraft and the flight paths of these aircraft.

4.26.Atpresent, no appeal can be lodged with the administrative courts against (an amendment to) the LIB and LVB. This follows from Article 1 of Appendix 2 to the General Administrative Law Act (Awb). However, it is possible to apply for enforcement of the rules and standards laid down in the Aviation Decrees through the administrative route.

The LVB 2004

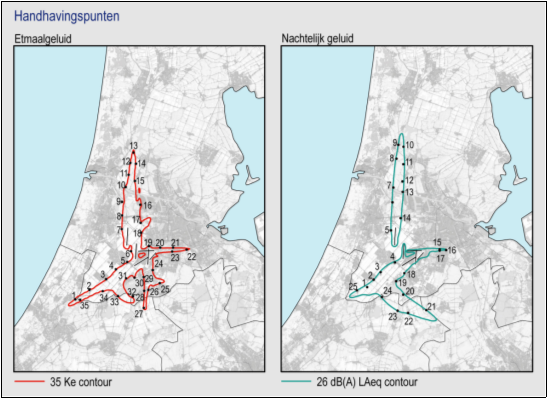

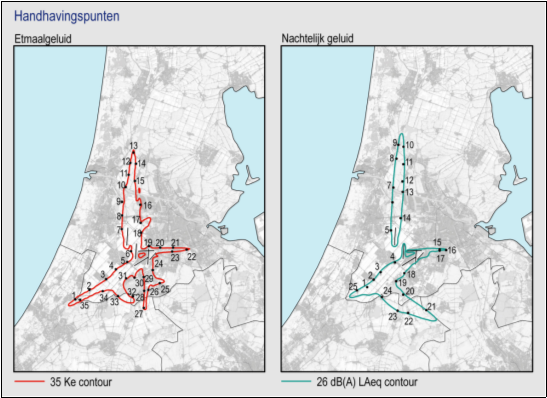

4.27.The LVB of 23 August 200450 (LVB 2004) is considered to be the first LVB. 51 In the LVB 2004, protection against noise was elaborated by setting limits on noise exposure in a ring of enforcement points in or near inhabited areas around Schiphol. These enforcement points are at or near the 35 Ke contour (for the noise exposure during the entire day) and at or near the 26 dB(A) LAeq contour (for noise exposure during the night (from 23:00 to 7:00)). The noise exposure at an enforcement point shall not exceed the limit value set for that point. This involves 35 enforcement points (with corresponding limit values) for noise exposure throughout the day and 25 enforcement points (with corresponding limit values) for noise exposure during the night (from 23:00 to 07:00), as shown in the figure below. A 52

4.28.The limit values for the enforcement points in the LVB 2004 have been set on the basis of the European noise indicators Lden and Lnight, in such a way that the preconditions for equivalence of Article XII of the Act amending the Wlv are met (see 4.21). 53 The baseline scenarios provided by the aviation sector were used for that purpose. These scenarios reflect the sector’s expectations of developments in certain years in the future; in this case, 2005 and 2010. In the Memorandum of Response to the Act amending the Wlv, the procedure is described as follows: 54

Input data derived from the baseline scenario were entered into a calculation model that calculates the noise exposure in Ke. The baseline scenario has been adjusted until the results of the calculation model meet the preconditions in Article XII of the bill (…) The EIA55 shows that these requirements have been met. This also means that the requirements set by the PKB have been met. Subsequently, a calculation was made again with the same input data, but this time for Lden. This calculation was performed for the enforcement points in the vicinity of the 35 Ke contour. The values found indicate the limit values in the enforcement points.

The limit values for noise exposure at night are set in the same way.

It follows from the Environmental Impact Assessment ‘Amendment of Schiphol Implementing Decrees’, March 2004 (hereafter referred to as: EIA 2004) that in the revised (traffic) scenario in 2005, rounded up, a maximum of 508,000 aircraft movements were possible. 56 The Explanatory Memorandum to the LVB 2004 states as follows:57

The EIA58 was presented to the competent authority by the initiators on 26 March. On 2 April 2004, the two ministers involved accepted the report. The alternatives examined in the EIA fall within the limits imposed on an equivalent transition from the first to the amended decisions. According to the initiators, the alternatives make it possible to achieve a maximum of 508,000 aircraft movements within the limits and applicable rules for noise. The EIA shows that, as a result of this scenario and the chosen distribution, the noise pollution around the airport will decrease for the Polderbaan Runway and increase for the Zwanenburgbaan Runway. This effect was intended and expected. Compared to the LVB and the LIB as they came into force on 20 February 2003, the noise exposure in the area near Zaandam will decrease, while the noise exposure in Amsterdam-West and Amsterdam-Noord will increase. This is due to more intensive use of one of the flight paths on the Zwanenburgbaan Runway. In addition, as a result of a lower limit value scenario, there will be a reduction in noise exposure on the other runways.

4.29.It also includes the following:

3. According to the respondents, there is no correct representation of reality due to the use of outdated data (including 1990 housing censuses) or inadequate data that cannot be verified.

Many speakers indicated that the comparison with the situation in 1990 did not give a good picture of the situation. In the meantime, many houses have been built in Velsen, among other places, whose residents feel misunderstood in the housing censuses included in the guidelines for the EIA.

– The competent authority understands the reaction of the speakers. There is, however, a motive for reflecting the environmental effects with the 1990 data. In the PKB, 1990 was the reference situation for the standards for Schiphol’s five-runway system. This reference is in the Law of 27 June 2002 (Stb. 374; «Schiphol Act»). As in the earlier EIA, the EIA Schiphol 200359, the reference situation for 1990 was therefore assessed.

– Of course, it is not the case that the developments after that are not important, and that people who did not live there are not taken seriously. That is why the EIA also contains a representation of the most current situation. A 60

4.30.The exact limit values are laid down in Articles 4.2.1(3) and 4.2.2(3) of the LVB 2004 and the annexes therein. Paragraph 2 of the abovementioned articles stipulates that the limit value for the whole day is 63.46 dB(A) Lden and the limit value for the night is 54.44 dB(A) Lnight.

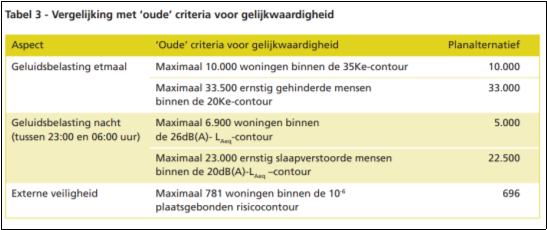

4.31.Application of the equivalence criteria led to the following limit values for the level of protection provided for in the LVB 2004:61

| Parameter | Limit

2004 |

| the number of dwellings in the 35 Ke contour | 10.000 |

| the number of seriously inconvenienced people within the 20 Ke contour | 33.500 |

| the number of dwellings within the 26 dB(A) LAeq contour | 6.900 |

| the number of severely sleep disturbances within the 20 dB(A) LAeq contour | 23.000 |

Because these are the limit values of the first LVB, each subsequent LVB must be assessed against these limit values on the basis of Article 8.17(7) of the Wlv.

the LVB 2008

4.32.In 2006, in response to the results of, among other things, the evaluation of Schiphol’s policy as laid down in Chapter 8 of the Wlv, the LIB and the LVB, and the analysis of the development of mainport Schiphol, the government made proposals to adjust the policy. The following two principles were used:

In the first place, the government wants to maintain Schiphol’s position as one of the most important ‘hubs’ (a hub of connections) in Northwest Europe. The government wants to ensure that there is room for growth for the further development of Schiphol.

Secondly, the government recognises that air traffic causes nuisance in the wider vicinity of Schiphol and wants to reduce this nuisance as much as possible, especially in the area further away from the airport, where most people who are affected by air traffic live, the so-called “rural area”. A 62

With regard to the level of protection to be afforded by the new policy to be formulated, the following observations are made, inter alia:

The government has concretised the legal precondition for a level of protection that is equivalent to or better than the level of protection of the first Airport Decrees on the basis of the following principles.

• The government uses the most recent scientific insights into safety risks, noise pollution, Schiphol’s current aircraft fleet and the most recent housing situation. The best insights on the relationship between aircraft noise and nuisance are used, the latest safety models, and the most recent data on aircraft safety. This update does not lead to more or less capacity of air traffic.

• In addition, the government wants that if new insights emerge at a later stage, these lessons will also be used for possible future policy changes.

• The government is also separating the responsibilities between the aviation sector and regional governments. If new people are hindered by new housing, the aviation sector will not be held accountable for this.

• The number of people seriously annoyed by aircraft noise may not increase in the event of an amendment to the Airport Decrees compared to the maximum that was possible under the first Airport Decrees. As with the first Airport Decrees, there is a limit for the number of people annoyed with a high noise exposure (more than 58 dB Lden, comparable to the 35 Ke used for the first decisions) and a limit for the number of people annoyed with a lower load. Because most of the people affected live further away from Schiphol, the government is increasing the area in which the amount of nuisance is assessed from approximately 52 dB Lden (comparable to the 20 Ke used for the current Airport Decrees) to 48 dB Lden. The 48 dB Lden is a noise level that still causes nuisance to a reasonable proportion of local residents and that can be determined with a reasonable degree of accuracy.

• The number of people with sleep disturbances may not increase compared to the maximum that was possible within the first Airport Decrees. For this too, the government wants to increase the area in which sleep disturbance is taken into account (from 48 dB to 40 dB Lnight), because most sleep disruptors live further away from the airport. A 63

4.33.As a result, in 2007 the equivalence criteria (and therefore also the parameters) of the first LVB, LVB 2004, for noise nuisance, among other things, were updated, because the data on which those criteria were based were very outdated. 64 The new criteria were calculated on the basis of the same traffic scenario as that used to determine the protective effect of LVB 2004, with the result that the update would not lead to more or less room for growth for air transport, nor would it lead to more or less nuisance. A 65

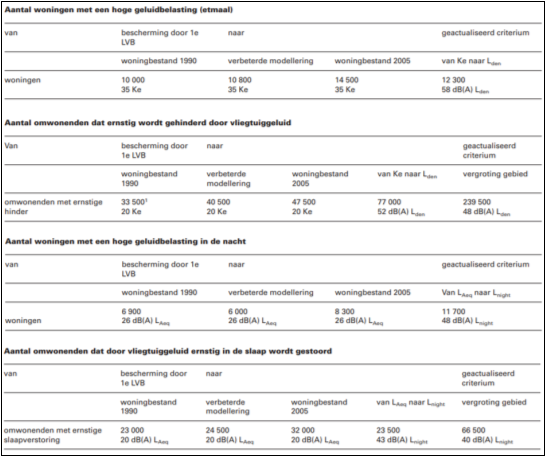

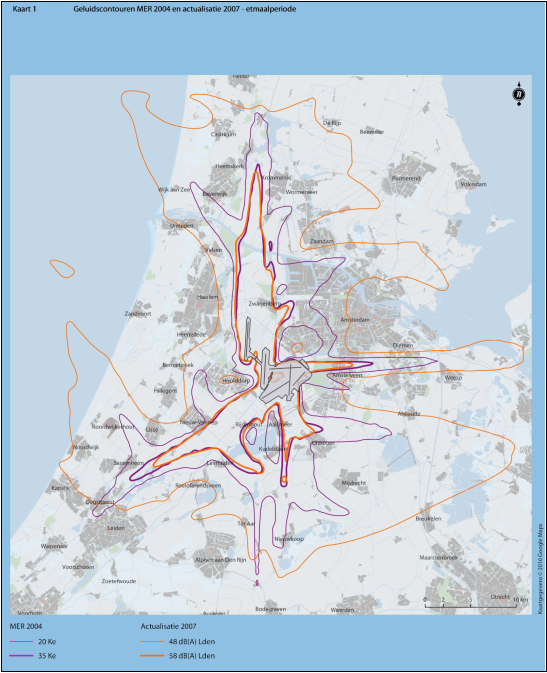

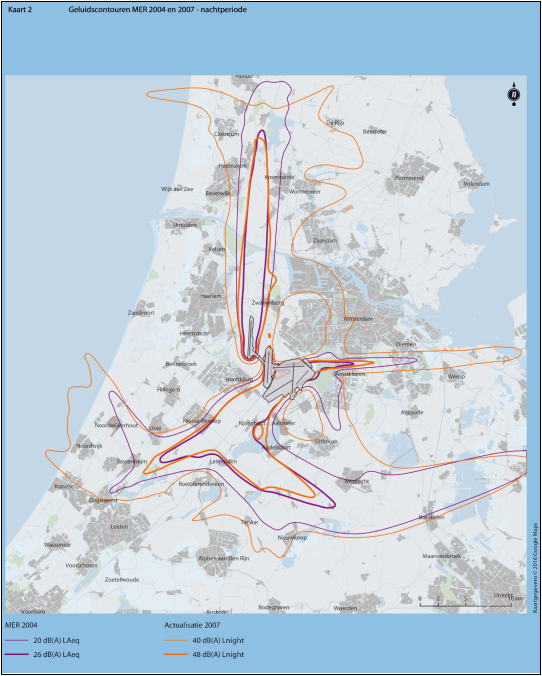

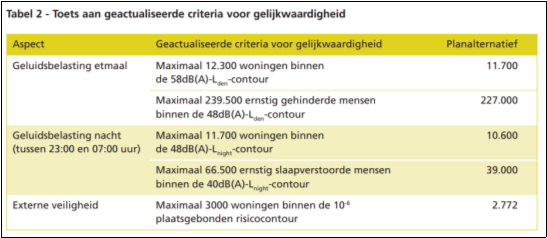

4.34.

In order to achieve the update, the housing stock was first updated; The housing stock of 1990 was no longer taken into account, but that of 2005. In addition, the Dutch sound measures Ke and LAeq were replaced by Lden and Lnight. As a result, the 35 Ke contour has been changed to the 58 dB(A) Lden contour and the 26 dB(A) LAeq contour to the 48 dB(A) Lnight contour. The choice of the European noise standards meant that the existing BR relationships (based on the Dutch standards) could no longer be used. These BR relationships, which were also based on research from the 1960s, have been replaced by new BR relationships based on the GES-2002. 66 Route modelling was also based on actual flight patterns, so that a more realistic picture for noise exposure could be identified.

Finally, it has been decided to use a larger area than before to determine the number of seriously annoyed and sleep-disturbed people in order to gain more insight into the nuisance and sleep disturbance in areas further away from the airport. This led to a widening of the noise contours. 67 The effects of the various updates in 2007 are set out below. A 68

4.35.This led to the following limit values that the level of protection of the LVB 2008 had to meet:

| Parameter | Limit

2007 |

| the number of dwellings in the 58 dB(A) Lden contour | 12.300 |

| the number of seriously annoyed persons within the 48 dB(A) Lden contour | 239.500 |

| the number of dwellings within the 48 dB(A) Lnight contour | 11.700 |

| the number of severely sleep-disturbed people within the 40 dB(A) Lnight contour | 66.500 |

4.36.In his letter of 25 May 2007 to the House of Representatives, the Minister of Transport, Public Works and Water Management69 (hereinafter referred to as the Minister) made the following remarks about the change in the limit values brought about by the update:70

Article XII(c) of the Aviation Act states: «The 35 Ke contour includes a maximum of 10,000 dwellings, determined in accordance with the manner in which this number has been determined in the PKB Schiphol and Surroundings». The criteria for equivalence are thus linked to the method of calculation. If the method of calculation changes (in this case due to the new route modelling), this will result in an increase of 800 for the maximum number of dwellings in the 35 Ke contour. On the other hand, the maximum number of homes with high noise exposure at night decreases by 900 homes in the inner area.

The other option put forward by the MNP, scaling back the volume of traffic during the day so that the number of dwellings within the 35 Ke reaches 10,000, is contrary to the precondition as formulated in the Cabinet’s position on Schiphol that the update must not lead to more or less room for growth for aviation.

4.37.These updated limit values form the basis for the equivalence test in future amendments to the LIB and the LVB. A 71

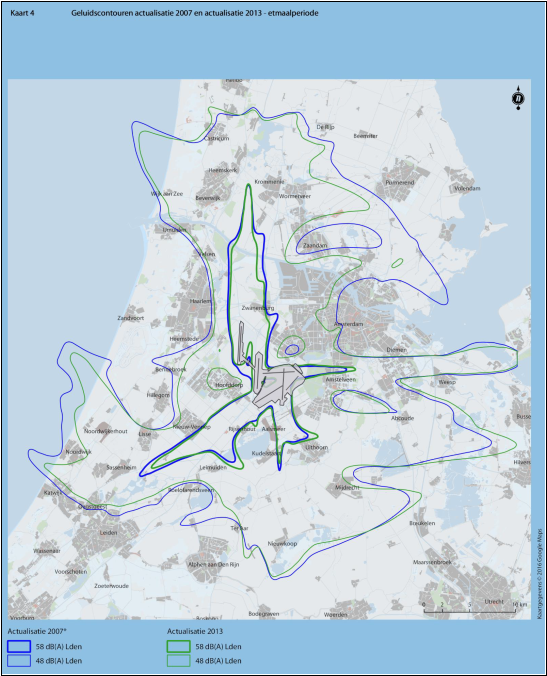

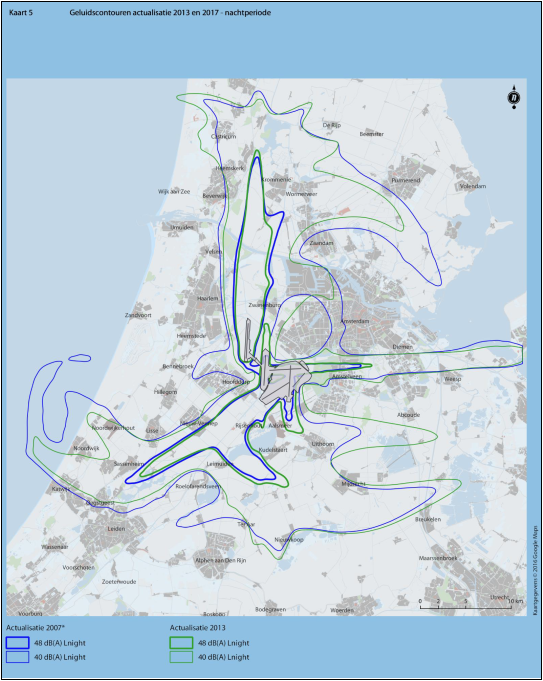

4.38.The consequences for the noise contours for the day and night periods are visible on the maps below:72

4.39.Subsequently, in 2008, the LVB 2004 was amended. In the LVB 2008, the limit values for a number of enforcement points have been changed in order to make it possible to make a ‘better use of the environmental space’ within the requirement prescribed by law for equivalent or better protection of the environment. It had become apparent that at some enforcement points the limit value was (almost) reached or had been exceeded, while at other points there was still noise room left. The amendment to the LVB would prevent stagnation in the development of Schiphol’s network function and create room for growth for Schiphol. Adjustment of the limit values of the enforcement points could increase the number of aircraft movements in the short term (until 2010) to 480,000 on an annual basis. 73 The updating of the limit values therefore meant that, within the requirements of equivalent protection, the limit values at the enforcement points were redetermined by means of current insights concerning, inter alia, the actual handling of traffic (runway and route use) and/or traffic scenarios. The starting point was that the other parts of the LVB would remain the same. A 74

4.40.In 2013 and 2017, the equivalence criteria were updated twice. 75 This concerned an update of the methodology for modelling runway and route use from a theoretical model76 to an empirical model in 2013 and from an empirical model to a hybrid model in 2017. In 2017, new flight procedures were also added to the flight procedure modelling and the aircraft noise model was updated. 77 The results of those updates for the limit values are set out in the table below.

| Parameter | Limit value 2013 | Limit value 2017 |

| the number of dwellings in the 58 dB(A) Lden contour | 12.200 | 13.600 |

| the number of seriously annoyed persons within the 48 dB(A) Lden contour | 180.000 | 166.500 |

| the number of dwellings within the 48 dB(A) Lnight contour | 11.100 | 14.600 |

| the number of severely sleep-disturbed people within the 40 dB(A) Lnight contour | 49.500 | 45.000 |

4.41.The consequences for the noise contours for the day and night period are visible on the maps below:78

4.42.

In 201079, 201280, 201681 and 201882 there were some adjustments to the LVB 2008. These adjustments were related to changed arrival and departure routes and changed limit values, the extension and advance of the night period and the setting of a maximum of 32,000 night flights.

The new standards and enforcement system Schiphol (NNHS)

4.43.In addition to the updating of the equivalence criteria and the adjustment of the limit values by amending the LVB, the lack of flexibility of the system of enforcement points laid down in the LVB (see 4.19 and 4.27) was a reason to push for a change in the system. To this end, the ‘Alders Table’ was created. In this consultative body, chaired by former Minister Alders, the national government, the aviation sector, administrators and residents from the vicinity of Schiphol were represented. 83 The Alders Table was asked to examine how a workable agreement could be made in the medium term that would make use of the available environmental space (criteria for equivalence) for Schiphol and that would achieve a balance between the development of aviation, nuisance reduction measures, increasing the quality of the living environment and the possibilities for using the space around the airport. A 84

4.44.On 1 October 2008, the Alders Table issued an (interim) advisory report on the medium-term future of Schiphol and the region. The advisory report proposed a new Schiphol standards and enforcement system (NNHS) that was seen as less complex and more transparent than the current system of regulation via limit values in enforcement points. The proposed system was based on the system of strictly preferential runway noise use. 85 That meant using, as far as possible, a combination of runways which would give rise to the least noise pollution at that time. The use of these runway combinations can be used to ensure that as little as possible is flown over densely populated areas, provided that weather conditions permit, among other things. This was elaborated in the following four lines:

1. the first rule focuses on the use of the most noise-preferred runway combination; 2. the second rule is aimed at ensuring that no second runway (the so-called secondary runway) is used if the volume of traffic does not exceed the capacity of the most noise-preferred runway;

3. the third rule specifies how traffic is to be distributed between two runways or two runways in the event that two runways or two runways are in use due to a take-off or landing peak; and

4. The fourth rule sets a maximum number of movements on the fourth lane. A 86

4.45.In addition, the proposal includes the system of maximum permissible noise level (MHG) to replace the TVG. The MHG is a sum of the noise that can be produced within the equivalence criteria, when a chosen scenario for the use of the airport in a given year is assumed. This amount of noise corresponds to the amount of noise at which one of the criteria for equivalence is reached (or several at the same time). The rules for runway use determine the local distribution of the noise exposure and therefore also the location of the contour. The MHG is determined annually. A 87

4.46.After experiments with the NNHS from 1 November 2010 to 1 November 2012, the Alders Table recommended in 2013 that this system should be enshrined in law. This advice has been adopted by the government. In anticipation of this legal anchoring, traffic management has so far been carried out in accordance with the rules of strict preferential runway use.

4.47.In a letter dated 25 September 2015, the Minister informed the House of Representatives as follows: 88

Until such time as the new system of standards and enforcement in the Aviation Act and underlying regulations is definitively in force, anticipatory enforcement will be carried out in the enforcement points if the limit values are exceeded – assuming that the law is dealt with expeditiously. This means that no measure will be imposed if the limit values are exceeded if it appears that the exceedance is the result of the application of the rules of the new system. This will be assessed at the end of the year of use. (…)

4.48.The NNHS is enshrined in a bill to amend the Wlv. That bill was passed in 2016, but the law has not yet entered into force. In addition, a draft of the LVB has been drawn up in which the NNHS is anchored (LVB NNHS). That draft was sent to the Senate and House of Representatives on 16 February 2021 as part of the preliminary procedure laid down in the Wlv. Unlike the previous LVBs, the LVB NNHS design includes a maximum number of aircraft movements. This concerns a maximum number of 500,000 movements per year of use, of which a maximum of 29,000 at night. The draft LVB NNHS also includes the new, updated equivalence criteria set out below. This is based on the housing stock of 2018. A 89

| Parameter | Limit

2018 |

| the number of dwellings in the 58 dB(A) Lden contour | 12.000 |

| the number of seriously annoyed persons within the 48 dB(A) Lden contour | 186.000 |

| the number of dwellings within the 48 dB(A) Lnight contour | 12.800 |

| the number of severely sleep-disturbed people within the 40 dB(A) Lnight contour | 50.000 |

4.49.In April and November 2021, the Minister informed the House of Representatives that the aim is still to anchor the LVB NNHS as soon as possible, but that this may take some time due to the ongoing complex procedure for a nature permit for Schiphol. 90 In a letter of 19 April 2021 from the Minister to the House of Representatives, it was stated, inter alia, as follows:

This [court: the introduction of the LVB NNHS] is important because otherwise there will remain a legal vacuum in which the rules of the NNHS, including the maximum capacity of 500,000 aircraft movements, are flown in accordance with the rules of the NNHS, but this is not formally enshrined in legislation and regulations. The end of anticipatory enforcement is therefore necessary to improve the legal position of local residents and because of court rulings in this regard.

4.50.The LVB NNHS has still not entered into force.

The European Noise Regulation

4.51.Since 13 June 2016, the European Noise Regulation91 has been in force. This Regulation lays down rules for the introduction of noise-related operating restrictions for airports. The rules are based on the principles of the balanced approach to aircraft noise management agreed by the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). 92 Where a Member State wishes to implement noise-related operating restrictions, the so-called balanced approach procedure must be followed. Noise-related operating restrictions should only be introduced when other measures of the balanced approach are not sufficient to achieve the specific noise abatement objectives. Before Member States can introduce operating restrictions, they must notify the other Member States, the European Commission and the relevant interested parties six months in advance. The Commission may review the procedure within three months of receipt of the notification. If the Commission considers that the procedure has not been complied with, it shall inform the Member State, which in turn shall inform the Commission of the actions it intends to take before the operating restriction is introduced.

Enforcement of the LVB

4.52.The Human Environment and Transport Inspectorate (ILT) is responsible for enforcing the LVB and is responsible for ensuring that Schiphol, Air Traffic Control the Netherlands (LVNL) and the airlines that use Schiphol comply with the LVB standards. For each enforcement point, the ILT assesses the calculated amount of noise against the limit value as it applies in the relevant year of use. This is done at the end of a year of use on the basis of the actual air traffic in that year. If a limit value from the LVB is exceeded, the ILT is in principle obliged to impose measures to prevent the exceedance from occurring again. However, as is also apparent from the Minister’s letter cited under 4.47 above, since the start of the NNHS experiment, no consequences have been attached to the exceedance of limit values if that exceedance is the result of flying in accordance with the rules for preferential runway use.

4.53.Since 2014, the limit values have been exceeded for several enforcement points per day. 93 In 2016, 2017 and 2018, there was an exceedance in four enforcement points, in 2019 in five enforcement points, and in 2021 in one enforcement point. These exceedances in 2017, 2018 and 2019 were the result of flying according to the rules of the NNHS. This did not apply to the exceedance in 2021. As a result of this exceedance, the ILT has imposed measures on Schiphol and LVNL. A 94

Compensation for loss

4.54.In 1998, the Schiphol Airport Claims Board was established to deal with claims for compensation related to the PKB and its subsequent decisions. The Schadeschap was dissolved on 1 June 2020. The tasks of the Schadeschap were then transferred to the claims desk of Rijkswaterstaat.

4.55.Since 2023, residents living in the vicinity of Schiphol have been able to qualify for compensation for loss of enjoyment of their home on the basis of the Policy Rule on Compensation for Compensation for Loss of Noise Noise at Schiphol Airport as a result of exceeding the limit value in an enforcement point near their home against which the ILT has not taken action due to the principle of anticipatory enforcement. A 95

Actual measures

4.56.In addition to regulating noise pollution, actual measures are also being taken to reduce the negative effects of air traffic to and from Schiphol.

4.57.In the period 1984-2012, approximately 13,000 noise-sensitive objects were insulated as part of Schiphol’s sound insulation policy. The Schiphol 202396 Façade Insulation Regulations aim to insulate approximately 660 homes that are exposed to a noise exposure of 60 dB(A) Lden or higher. In line with the intended reduction in the number of aircraft movements (see 4.74 below), the determination of this noise contour is based on 440,000 aircraft movements.

4.58.In order to (further) limit the nuisance caused by air traffic to people living in the vicinity of Schiphol, the participants in the Alders Table laid down a number of nuisance mitigation measures in the 2008 covenant on the reduction and development of Schiphol in the medium term covenant on the development of Schiphol’s capacity (a maximum of 510,000 aircraft movements per year in the period 2010-2020) and the (noise-preferential) runway use, among other things. By 2020, the total package of nuisance mitigation measures had to lead to a reduction of at least 5% of seriously annoyed people in the 48 dB(A) Lden compared to the limit for equivalence. According to the agreement, equivalence is defined as: 97

equivalence according to the equivalence criteria based on Article 8.17 paragraph 7 of the Aviation Act, as most recently updated by letters from the Minister of V&W to the House of Representatives of 25 May 2007 and 3 March 2008.

Examples of these measures are the modification of flight paths, the installation of noise ridges and the extension of the duration of the night procedures for landing and take-off air traffic.

4.59.During the evaluation of the agreement in 2013, the Alders Table pointed out that the possibilities of nuisance-reducing measures are being exhausted. The parties to the consultation point out that the most promising and significant nuisance reduction has already been achieved and that further local optimisation will most likely be at the expense of other areas. According to the Alders Table, new opportunities are limited to possible innovations in take-off and landing procedures and in fleet development. The evaluation concluded that the 5% nuisance reduction in 2020 will be achieved with the measures implemented up to and including 2012. A 98

4.60.In response to a letter to Parliament from the Minister dated 5 July 2019, Schiphol and the LVNL have drawn up an implementation plan for nuisance reduction, which includes measures to limit nuisance. The public will be kept informed of the implementation of these and new measures via the www.minderhinderschiphol.nl website. One such measure is the use of quieter aircraft. Airport charges encourage the use of these aircraft and discourage the use of old, noisy aircraft. The amendment to the Regulations on Operational Restrictions for Noisy Aircraft at Schiphol should also contribute to this.

Noise pollution around Schiphol

4.61.In 2022, research was conducted into the noise exposure (Lden and Lnight) of air traffic around Schiphol in the period 2012-2018. 99 Data from monitoring stations of the Noise Monitoring System around Schiphol (NOMOS) were used for that purpose. 100 It is apparent from that study that, during that period, the total (measured) noise exposure decreased by 3.6 Lden and 3.1 Lnight, while the number of flight movements increased. According to the researchers, the decrease in noise exposure can be (partly) explained by the fact that aircraft have become quieter.

4.62.The Compendium for the Living Environment shows that despite the growth in trade traffic in the period 2000-2018, the total area of the areas within the 48 and 58 dB(A) Lden contours has changed little in that period. A 101

Serious noise nuisance and sleep disturbance around Schiphol

Within the noise contours set out in the equivalence criteria

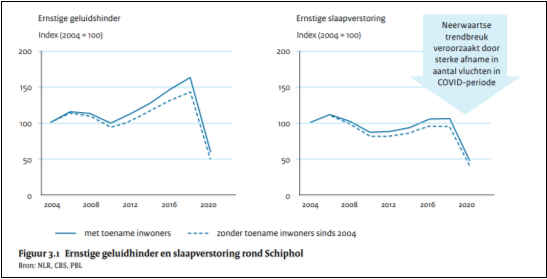

4.63.In the National Environmental Vision Monitor 2022102, the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) has provided insight into the development of the number of seriously annoyed and (severely) sleep disturbed people within the noise contours included in the equivalence criteria. A distinction has been made between the situation in which the increase in the number of inhabitants due to the increase in the number of dwellings has been taken into account and the situation in which this increase is not taken into account. The latter is in line with the political choice not to blame aviation for the increase in nuisance caused by more housing (see 4.32).

4.64.PBL notes that the serious noise nuisance for people living in the vicinity of Schiphol who are exposed to a noise exposure of 48 dB(A) Lden or more has increased sharply since 2004 until 2018 (the year in which Schiphol almost reached its maximum capacity of 500,000 km/h) (the first full year with the five-runway system); by about 40% without taking into account the increase in the number of inhabitants due to housing construction and by about 60% if this is taken into account. In 2018, 173,000 of the 819,000 inhabitants within the area experienced serious nuisance with a noise exposure of 48 dB(A) Lden or more. In that year, (severe) sleep disturbance occurred in approximately 22,000 of the 220,000 inhabitants within the 40 dB(A) Lnight. A 104

Outside the noise contours included in the equivalence criteria

4.65.As part of the evaluation of Schiphol’s policy, the MNP has tried to map out the actual extent and the effects of air traffic on the entire area where nuisance caused by air traffic is an issue. Among other things, it was found that in the period from 1990 to the opening of the fifth runway, total noise pollution from air traffic was reduced by about 40% as a result of, among other things, the arrival of new, quieter aircraft. For the period after the commissioning of the fifth runway, the research report notes that noise pollution is expected to stabilise during that period and sleep disturbance to increase slightly (+20%). 105 The MNP determined the extent of the serious noise nuisance within the noise contours set out in the equivalence criteria by comparing the BR relationships based on the GES 2002 in relation to the total noise nuisance within the study area. This shows, among other things, that in 1990 and at the time of reporting (2005) approximately 3% of the total number of seriously disturbed people within the total study area lived within the 35 Ke-contour and that 1 to 2% of the total number of (severely) sleep disturbed lived within the 26 dB(A) Laeq contour. A 106

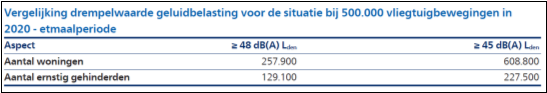

4.66.The fact that serious noise nuisance and sleep disturbance occur (much) more often in the areas outside the noise contours included in the equivalence criteria is confirmed, among other things, in studies by the GGD Kennemerland from 2016 and 2020107, the RIVM report from 2019 to be discussed below and in the Environmental Impact Assessment ‘New Standards and Enforcement System Schiphol‘, November 2020 (hereinafter: EIA 2020). The latter report provides insight into the situation of 500,000 aircraft movements in 2020 as to how many homes and seriously inconvenienced people are located in the area with a noise exposure of 45 dB(A) Lden or more, with the caveat that it is uncertain whether the calculation model used and the input data are suitable for mapping this accurately.

It is concluded that the number of dwellings and seriously disturbed persons in the area with a noise exposure of 45 dB(A) to 48 dB(A) Lden is approximately twice as high as the

numbers in the area with a noise exposure of 48 dB(A) Lden or more. The area with a noise exposure from 45 dB(A) Lden is also approximately twice as large as the area with a noise exposure from 48 dB(A) Lden. A 108

WHO Guidelines

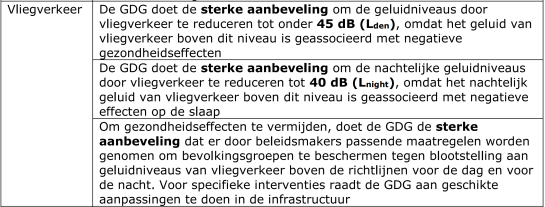

4.67.In 2018, the World Health Organisation (WHO) made recommendations for the protection of public health against exposure to noise caused by road traffic, rail traffic, aviation and wind turbines in the ‘Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region‘. The WHO guidelines are based on the latest scientific insights into the health effects of noise. The following recommendations have been formulated for the noise exposure caused by air traffic:109

4.68.In deriving the health-based recommended values included in the recommendation, the WHO used a research method that determined, among other things, the level to which it is acceptable for a health effect that is considered relevant and critical (indicated as a health endpoint) to occur and at what noise level that level is reached. This has been determined for, among other things, serious noise nuisance and sleep disturbance. It can be deduced from the report that, according to the WHO, it is acceptable if 10% of the exposed population is seriously bothered by noise and 3% is disturbed by sleep. This level is reached at 45.4 dB(A) Lden for serious nuisance caused by air traffic. 110 A certain priority was given to all the health endpoints considered relevant and critical, and that prioritisation ultimately led to the recommended values set out in the recommendation. At a nocturnal noise level of 40 dB(A) Lnight, as recommended by the WHO for air traffic, 11% of the exposed population will be sleep disturbed. Although this percentage is higher than the level considered acceptable, a lower value has not been recommended due to the lack of reliable data to support it. A 111

4.69.In 2019, RIVM was commissioned by the then government112 to conduct research into the relationship between the WHO guidelines and the applicable laws and regulations in the field of environmental noise and the possibilities of using the WHO guidelines to strengthen national and international noise policy.

4.70.The report shows, among other things, that in the Netherlands 2,097,800 people (12% of the total population) are exposed to a noise level from air traffic that is greater than or equal to the WHO recommended value for the entire day and 219,800 people (1% of the total population) to a noise level greater than or equal to the recommended value for the night. This concerns not only air traffic to and from Schiphol, but also to and from the other airports in the Netherlands. The number of people aged 18 years and older who are seriously affected is estimated at 259,200. This estimate was based on the BR relationships based on the GES 2002. According to the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), the size of the number of people seriously annoyed by air traffic noise is mainly determined by noise levels in the range of 45-50 dB(A) Lden. More than 76% live in an area where the noise level is higher than the WHO recommended value. The number of sleep disruptors (aged 18 years or older) is estimated at 151,900. They mainly live in areas with a noise level between 32 and 37 dB(A) Lnight, i.e. lower than the WHO recommended value. A 113

4.71.In its report, RIVM has made a number of general recommendations and a number of recommendations that specifically relate to the noise exposure of air traffic, including the following: 114

General:

– The National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) recommends strengthening the policy on ambient noise by embedding health improvement as a stand-alone goal in Dutch legislation and regulations. This anchoring provides a more concrete interpretation of the general concepts in the (current and announced) regulations on the protection or improvement of the health and quality of the living environment. As a result, health improvement can also become a leading factor for changes in the living environment, rather than a possible consequence of the obligation to weigh up an expected increase in the noise level. The WHO guideline recommends giving health greater weight in policy considerations about environmental noise. In the Netherlands, this ‘rethinking’ requires a ‘standstill’ approach to a policy that is in principle aimed at reducing the negative health effects of noise. This approach is in addition to the existing policy commitment to prevention and remediation.

Specific:

– RIVM recommends that people outside the current focus area be taken into account when developing and implementing the policy. This area is defined by defined contours. The distribution of the current burden of disease shows that the majority of people who experience negative health effects from air traffic noise are outside the defining contours. At the same time, the areas with the highest noise levels should not be overlooked.

– The National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) recommends conducting research into the influence of noise dynamics on negative health effects. Insight into this may have consequences for the environment and/or composition of the relevant group.

– The most up-to-date BR relationship for annoyance, sleep disturbance and coronary heart disease should be used to determine the relevant group;

– Subsequently, the goal for health improvement can be determined based on an understanding of the relevant group. The relevant group can serve as a basis for decisions on spatial developments or action plans in the context of the END.

– Health improvement can be achieved by limiting the permitted noise allowance [court: the noise allowance indicates the maximum amount of noise that may be produced and how high the noise exposure may be in the surrounding area], which means that measures must be taken to reduce noise production. It is possible that prescribed technical source measures can fill in part of the required reduction. (…)

4.72.Commissioned by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, the impact of using the WHO criteria was analysed. In this analysis, it was established that, based on the number of 500,000 aircraft movements per year included in the LVB NNHS and the housing stock of 2015, 660,000 homes are located within the 45 dB(A) Lden contour. Within the 48 dB(A) Lden contour, there are 275,000. Within that 45 dB(A) Lden contour, the number of seriously annoyed persons, based on the GES2002-based BR relationships, is estimated to be 246,000 compared to 135,000 within the 48 dB(A) Lden contour. According to the analysis, the number of dwellings and (severely) sleep disturbed at night also increases sharply for noise exposure at night, based on the 40 dB(A) Lnight contour. A 115

Proposed policy

Aviation Policy Memorandum 2020-2050

4.73.The coalition agreement of 10 October 2017 stipulates that Schiphol’s policy in this regard will be changed and the focus will be placed on nuisance reduction and the quality of the living environment and air quality instead of on the number of aircraft movements. The aim is to find a new balance between the quality of the living environment and the quality of Schiphol’s network. To elaborate on this, in November 2020 the Minister published the report ‘Responsible flying towards 2050. Aviation Policy Memorandum 2020-2050‘. It has been elaborated that the public interests are central to the growth of aviation. Growth is possible within the preconditions set by the public interests formulated in the memorandum. This concerns safety, connectedness, quality of life and sustainability. If we succeed in reducing the negative effects of aviation on the climate and living environment compared to the situation in 2019, there may be room for growth. 116 In order to improve the quality of the living environment, limits will be set on noise pollution from airports and efforts will be made to reduce noise pollution from aircraft. It has been agreed that work will be carried out on the revision of the airspace with the aim of steering towards a more accurate use of flight paths and preferential minimum flight altitudes in order to reduce noise pollution. A 117

The three tracks of Schiphol’s Outline Policy

4.74.On 24 June 2022, the government announced that it would work towards a new balance between the importance of an international airport for the Netherlands on the one hand and the quality of the living environment around Schiphol, specifically for local residents, on the other, through the Schiphol Outline Decree (hereinafter: the Outline Decree). 118 As regards the balancing of interests carried out in that context, the following observations are made:119

In the interests of local residents, the government has given priority to noise nuisance around the airport. For the broad public interest of Schiphol, the number of flights needed to maintain the high-quality network of destinations worldwide, which makes the airport of value to the economy and business in the Netherlands, was examined.

Based on the balance of interests, the government has opted for reducing nuisance compared to the period before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, ending anticipatory enforcement and ensuring that the Netherlands is adequately connected to the rest of the world. This results in a reduction of the maximum number of permitted aircraft movements to and from Schiphol to 440,000 per year, instead of the 500,000 aircraft movements that were included in the draft Airport Traffic Decree (LVB) and that were already realised in practice before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. A reduction in the number of aircraft movements leads to less noise pollution and fewer emissions of CO2, nitrogen, (ultra)fine particles and other harmful substances. This is a necessary contribution from the aviation sector. The government is aware that this decision will have major consequences for the aviation sector.

4.75.The decision to achieve a reduction to 440,000 aircraft movements is based on various studies. Among other things, an analysis has been carried out to determine whether a reduction in the number of aircraft movements in the coming years will still be able to maintain an adequate network of connections with the rest of the world. As a result, a bandwidth of roughly 400,000 to 440,000 aircraft movements applies. The choice to opt for the number of 440,000 aircraft movements is explained as follows:

(…) Whichever methodology is used, a statement about the size of Schiphol in relation to maintaining network quality and the attractiveness of the business climate will always be surrounded by dilemmas and uncertainties.

(…)

Taking into account the uncertainties outlined and the lack of control options, the picture is that adequate accessibility of the Netherlands will be possible in the coming years with 440,000 aircraft movements at Schiphol. (…)

The combination of the outlined need to end anticipatory enforcement and the desire to improve the quality of the living environment, and the expectation that the destination network will remain sufficient, has prompted the government to take a new maximum of 440,000 aircraft movements per year as a starting point for Schiphol.

4.76.The outline decision will be implemented in three tracks: (1) the end of anticipatory enforcement in combination with the continuation of strictly preferential runway use, (2) the establishment of a lower maximum number of aircraft movements in an amended LVB and (3) the development of a new system of standards for the ‘environmental use area’. A 120

I. Track 1

4.77.In a letter dated 1 September 2023, the Minister informed the House of Representatives about the progress of track 1. The letter states, among other things, the following:

The government will end anticipatory enforcement as of 31 March 2024. This can be used to restore the inadequate legal position of local residents. In order to maintain the strictly preferential use of runways – with the least nuisance to the surrounding area on balance – a (ministerial) experimental scheme has been drawn up. The consequence of the end of anticipatory enforcement and the introduction of the experimental scheme is that, in principle, there is room for 460,000 aircraft movements per year at Schiphol. This is comparable to the number of aircraft movements that are currently flown at Schiphol, partly as a result of operational limitations. The experimental scheme will take effect on 31 March 2024 and will have no effect on the already completed capacity allocation over the winter season 2023/2024. As a result, the number of aircraft movements over the 2024 operating year could exceed 460,000 by several thousand.

4.78.The experimental scheme was published in the Government Gazette on 11 September 2023. A 121

II. Track 2

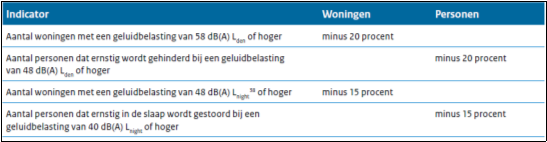

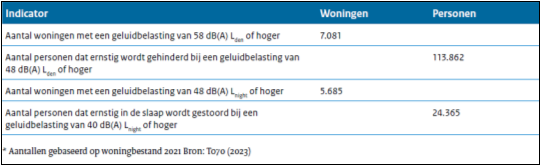

4.79.The government has set itself the goal of reducing noise pollution. The noise target to be achieved is formulated as follows:122

The traffic flow and the impact of noise exposure as of November 2024, based on the handling of 500,000 aircraft movements, of which 32,000 aircraft movements at night, (the situation in November 2024 without measures) will be the reference situation. In that situation, the noise exposure and noise nuisance are as follows:123

4.80.To give substance to the formulated goal, a combination of measures was notified to the European Commission on 1 September 2023 as part of the balanced approach procedure. These measures are:124

- –deployment of quieter aircraft at night;

- –reducing the use of secondary runways;

- –reduction of capacity at night to 28,700 flights; and

- –Reduction of capacity to 452,500 flights in total (day and night).

4.81.As a result of the notification and the discussions held in the context of it, the European Commission asked in-depth questions several times and asked for additional substantiation on parts of the proposed package of measures. In view of the time required to answer those questions and to supplement the substantiation, the Minister informed the House of Representatives on 25 January 2024 that it is unlikely that the balanced approach procedure for the allocation of slots for the 2024/2025 operating year will be completed. A 125

III. Track 3

4.82.In order to be able to steer the reduction of the negative effects of aviation in a structural way, a new system of standards is being developed, in which the environmental impact of the number of 440,000 aircraft movements is the upper limit. 126 In his answer to parliamentary questions about the design of the new system, the Minister made the following observations:127

In the development of the new system, it is important that it is possible to manage noise reduction and that the system contains possibilities to use additional (nuisance) indicators so that the system is as close as possible to the nuisance experienced by local residents.

4.83.On 14 November 2023, the first official elaboration of the new system was submitted to sounding board groups in which local residents, the aviation sector and administrative parties are represented, among others. A 128

4.84.The measures proposed in the context of track 1 have become the subject of summary proceedings initiated by various parties from the aviation sector. In those proceedings, they claimed, among other things, that – on pain of a penalty payment – the State be prohibited from adopting the proposed Experimental Scheme or a similar experimental scheme and from terminating anticipatory enforcement (or having it terminated). In a judgment of 5 April 2023, the preliminary relief judge in the District Court of Noord-Holland largely upheld the claims. The court in preliminary relief proceedings considered that the proposed Experimental Scheme will entail a capacity limitation and that its introduction without a balanced approach procedure having been followed is contrary to the Noise Regulation. In the opinion of the court in preliminary relief proceedings, the proposed Experimental Scheme, if adopted, is therefore unmistakably non-binding. According to the preliminary relief judge, this also applies to the State’s intention to stop anticipatory enforcement.

4.85.On 7 July 2023, the Amsterdam Court of Appeal set aside the judgment of the preliminary relief judge on appeal and dismissed the claims. The Court of Appeal is of the opinion that the proposed measures cannot be regarded as an operating restriction within the meaning of the Noise Regulation and considers the following, among other things:

4.19 (…)The Court of Appeal considers an interpretation of the Noise Regulation to the effect that the competent national authorities are obliged to follow the extensive and time-consuming procedure created by the Noise Regulation for a clearly defined and time-limited experiment such as the present one, whereby not only the European Commission, but also all Member States must be informed in violation of the nature and purport of that regulation. The text of the provisions of the Noise Regulation, in combination with the preamble, does not require such an interpretation. In the opinion of the Court of Appeal, if the interpretation advocated by IATA et al. were to be followed, whereby a short-term, clearly defined experiment such as the present one would also fall under the Noise Regulation, this regulation would go further than necessary and would therefore be contrary to the principle of proportionality under EU law. The conclusion of the Court of Appeal is therefore that the wording, the objectives and the scheme of the Noise Regulation do not preclude the introduction of an experimental scheme such as the one at issue without first going through the process of the balanced approach.

At present, therefore, it cannot be considered that there is a clear violation of the Noise Regulation if the proposed Experimental Regulation, or a variant similar to it in the relevant respects, is introduced without following the balanced approach procedure.

4.20The State’s stated intention to stop anticipatory enforcement essentially involves a repeal of the previously followed tolerance policy, whereby the limit values for noise exposure laid down in the LBV 2008 were not fully enforced. In the opinion of the Court of Appeal, the intention of a competent authority to enforce previously laid down limit values for noise exposure cannot be regarded as an operating restriction within the meaning of the Noise Regulation. In view of its objective and system, the Noise Regulation cannot have the purpose and therefore cannot be aimed at obliging the competent authority to first submit proposed enforcement measures or enforcement policy to the European Commission and all Member States and to go through the extensive balanced approach procedure for this purpose. Another starting point for this can be found in Article 14 of the Noise Regulation, which explicitly provides for compliance with noise-related operating restrictions that already existed on 13 June 2016.

4.86.In the opinion of the Court of Appeal, there are no other grounds to prohibit the State from adopting these measures. An appeal in cassation has been lodged against the judgment of the Court of Appeal. At the time of the hearing, a judgment from the Supreme Court was not expected before the end of the second quarter of 2024.