For decades, aviation visionaries have touted a coming revolution in avionics and piloting called “free flight,” when communications and computational technology will free commercial flying from the limitations and inefficiencies of ground-based traffic control. This year the next stage in free flight’s evolution will debut in Seattle, preparatory to a national roll-out, under the uplifting moniker Greener Skies. Those living in the flight path may find its auditory effects less uplifitng.

By relying on satellite-based GPS and onboard software, pilots will descend smoothly, precisely, and continuously to Sea-Tac, rather than loudly “stair-stepping” down in stages under ground-control direction. This will enable the airlines to reduce both their descent footprints — following tighter, narrower corridors — and their fuel consumption. For the residents of many communities alongside the descent corridors, this will mean less jet noise. But not for the most afflicted: those who live right under corridors that will become increasingly dense with descending jets.

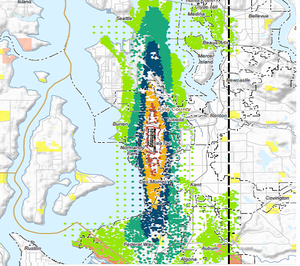

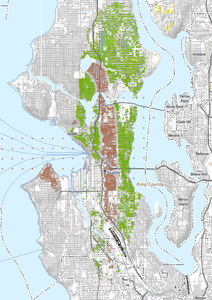

Greener Skies’ environmental assessment, which the Federal Aviation Administration approved in November, finds that noise impacts will diminish in broad vertical swaths from Wallingford and Fremont to downtown Seattle and Federal Way on the west and from Lake City to the Rainier Valley to the town of Pacific. But they’ll increase along the axis of Sea-Tac Airport’s runways, over Greenlake, the U-District, Capitol Hill, and, especially, Beacon Hill.

The reason, ironically, is greater efficiency: With GPS-guided continuous descent, air traffic will pack more tightly into the preferred north-south corridors and a diversion route over Elliott Bay (so Admiral and Alki will also get more noise). FAA officials contend that the additional noise impacts will be “indistinguishable,” less than 1.5 decibels more than present levels.

This news comes as a cruel joke to Beacon Hill residents, who’ve learned through long experience not to take the claims of aviation and airport officials at face value. Together with adjacent Georgetown, Beacon Hill is the most jet-rattled part of Seattle; it has suffered for decades from an excess of aircraft presence and an insufficiency of official concern. Sea-Tac’s north-flow departure route, used when the wind blows from the north, and south-flow arrival route, used when it blows from the south, run right along the hill’s long spine before diverging toward Elliott Bay and Lake Washington.

Living on Queen Anne, I used to snarl at the planes that occasionally roared overhead, mistaking or ignoring their designated approach over Elliott Bay. But I realized how much worse things could get when I spent a few summer hours in the otherwise tranquil Lockmore subdivision on Beacon Hill seven years ago. It was a shooting gallery; planes roared over in a stream, a minute or so apart. Conversation would stop, then resume when a particularly noisy one passed.

Otherwise, Beacon Hill, with its single-family character, wide views and proximity to downtown, would seem situated to be one of Seattle’s more desirable neighborhoods. Instead, the real estate site Zillow pegs its median home value at $289,500, just three-quarters the citywide median. “I sell homes here,” says real estate agent Erik Stanford, who’s lived on the hill for 25 years. “I used to tell people that unless you’re really sensitive, the noise isn’t so bad, that you get used to it. I can’t tell them that anymore.” Other residents say the same thing, only more vehemently.

FAA and Sea-Tac officials though, say flight volumes and noise impacts have actually declined in recent years, thanks to the recession and to the airlines flying quieter jets.

Stanford, who spearheads a Southeast Seattle group pointedly named the Quieter Skies Task Force, is the latest in a line of Southeast Seattle residents-turned-activists to take up the air noise cause. He struggles with the same challenges and frustrations as his predecessors: trying to organize a multilingual, multiracial community that’s tended to be fragmented and politically passive; dealing with a federal bureaucracy whose mission is all about moving planes, not safeguarding the quality of life down below; and complaining fruitlessly to an airport authority that monitors noise levels, but insists it can’t do anything to change them.

Even getting a meeting can mean running an obstacle course. In September, the FAA scheduled just two public meetings on the Greener Skies environmental assessment: in Federal Way for the corridor south of Sea-Tac and, for the north, in Ballard, which won’t be appreciably louder. It held the original scoping meetings last January in Federal Way and in Shoreline, which will actually get less noise under Greener Skies.

Why not on Beacon Hill, which will be more affected? FAA spokesman Allen Kenitzer says the meetings are arranged by a consultant who’s handling the Greener Skies roll-out nationwide, and are held where space is available. Stanford thinks it’s because they wanted to avoid the heat. He says there were more attendees in Ballard from Beacon Hill than from Ballard. They were disappointed to find that it was show-and-tell, with no opportunity to ask questions during the session.

The ensuing outcry (echoed by Mayor McGinn’s office) prompted FAA officials to schedule a meeting on Beacon Hill in October, where they would take questions. But about a week before, they cancelled that gathering, saying that key personnel wouldn’t be available then. That didn’t go down well. Erik Stanford had lined up interpreters and prepared a quadrilingual brochure for the meeting. Robert Bismuth, a Magnolia Community Club trustee and veteran of past FAA dealings cancelled a business trip to attend. When they cancelled the meeting on short notice, he says, “that sent a message to the community: You don’t count.”

The rescheduled meeting, in November at Cleveland High, did not go well either. The FAA reps seemed ill-prepared: no printed agenda, no signs directing attendees to the hard-to-find auditorium. About 100 attendees peppered them with sharp questions about flight routing and noise monitoring; they demurred on many, saying “Stan can explain that.” (Stan Shepherd, the manager of Sea-Tac’s noise programs, who seemed more informed and sympathetic.)

Such hand-offs are all too familiar to noise-weary, jet-wary citizens. “If you call the Port of Seattle to complain about noise, they’ll take a complaint and say, ‘It’s out of our hands, you need to talk to the FAA,’” sighs Stanford. “It’s a terminal condition — the Port pointing at the FAA, the FAA pointing at the Port.”`

This daisy chain can take on a Wonderland quality. The Port tracks flight noise with 31 monitors distributed from North Seattle to Federal Way. According to Port spokesperson Perry Cooper, they “are used, together with a consultant who comes in and puts all the data together for airport noise around the country” to gauge noise impacts and determine mitigation.

The Quieter Skies group claims Southeast Seattle has gotten shortchanged on monitors. The district, which has 80,000 residents and lies right in the flight path, has just two monitors — on Beacon Hill and Brighton Playfield, while Federal Way, which lies farther from the airport, has four (and besides gets all the meetings). Quieter Skies urges, ambitiously, that six more be deployed around Southeast Seattle, in hopes that they’d prove that the noise there is worse than the FAA says and justify mitigation or remedial action.

Vain hope. Shepherd, the Port’s noise-control manager, says he has no idea why the monitors were deployed as they were, but it doesn’t matter; they don’t affect noise policies anyway. “Even though there might be more in some areas and fewer in others, noise monitors aren’t going to make any difference. Per FAA regulation [and despite what Port spokesman Cooper says], we cannot have a direct input of the noise monitoring data into the model used to gauge impacts.”

So what are the monitors good for? “It’s a kind of balance and check,” says Shepherd. “The noise monitors’ data is just used to answer questions from the community about impacts.” (The Port’s website says they also help it monitor airlines’ compliance.) In other words, they are a means of reassuring the public, not protecting it.

Beacon Hill doesn’t seem to be reassured.

In 1990, after heavy lobbying by the airline industry, Congress passed the Airport Noise and Capacity Act, which introduced noise standards around the nation’s airports and preempted more stringent local controls. According to those standards, the FAA will only fund mitigation — noise-proofing and, sometimes, property purchases— in a designated noise impact “contour” where the average aircraft noise level, as determined by a complex formula, is at least 65 decibels, with a 10 dB bonus added to late-night noise because of its extra impact. (Sixty-five dB is commonly described as the noise of a cash register 10 feet away.)

The air-noise activists note serious flaws in this metric: The “average” levels don’t seem to account for the frequency of flights, nor for exceptionally loud, low-flying jets. And the formula ignores the cumulative effects of multiple airports. Beacon Hill and several other Seattle neighborhoods lie in the flight paths of not just Sea-Tac but nearby Boeing Field (plus Renton’s smaller airport). Their combined impact may well be more than 65 dB, but again, says Shepherd, that doesn’t matter. “Boeing Field noise is not considered in our [noise impact] Part 150 calculations.”

The Port is currently redoing those calculations, for the first time in a decade, in a Part 150 Noise Compatibility Study prescribed under federal rules. Again, Federal Way has gotten more attention from the feds than Southeast Seattle: Part 150 public meetings have been held in the former but not the latter. Again, however, Shepherd vows that Southeast Seattle will get just as much help under the new noise mapping as Federal Way and nearly every other community in the region: zilch. Sea-Tac’s 65 dB contour, which currently runs in a narrow band from Tukwila to Des Moines, is projected to shrink by about half, thanks to quieter jets. Outside that band, FAA environmental specialist Kaylin Morgan told the restive Beacon Hill meeting in November, “there’s no remedy for it. There’s no money for it.”

Some other airport districts have nevertheless managed to break the 65 dB sound barrier. The Cleveland and Minneapolis airports secured federal approval for mitigation out to 60 decibels (which would include South Beacon Hill). One noise expert contends that other airports could do the same if neighboring cities cooperate in their zoning. But Shepherd insists these are one-off cases that don’t translate to Seattle: Cleveland’s just catching up on previously promised mitigation and Minneapolis International was forced to extend its boundary through a lawsuit by neighboring cities.

Minneapolis’s example might in fact be pertinent for Beacon Hill. “We’ve decided a lawsuit is the most effective way [to get action],” says Erik Stanford. His group doesn’t have any funds for a suit, but he hopes to enlist UW researchers and perhaps Seattle University law students.

Meanwhile, Ticiang Dianson, a recently retired director of Seattle Public Utilities’ environmental justice division, and a former EPA toxicologist, who now teaches at UW, are considering bringing their own action over the jet emissions released on neighborhoods with high rates of poverty and respiratory illness. The FAA’s response to such concerns has been “mammoth bureaucratic,” says Dianson. “They tried to placate us, but they wouldn’t do anything.”

Stanford relishes the prospect: “If we can go after the FAA and Port with the EPA behind us, we’re going to have a whole lot more leverage.” And they may be able to bring in even bigger guns without paying for lawyers. It has worked before, on Beacon Hill and in Magnolia.

Twice, in the late ’90s and in 2010, Columbia City realtor Ray Akers caught the FAA extending its northbound departure corridor to the east, past Beacon Hill and MLK Way and over the Rainier Valley (and Akers’ house), with no announcement or review. The first time, he says, the agency relented and restored the original routing. The second time it stonewalled, not even acknowledging the change. Akers got Congressman Jim McDermott’s office to demand an explanation. The FAA’s acting regional director replied that this “Plan Charlie” routing was necessary whenever “localized weather or clouds” impeded the ability of Boeing Field controllers to track Sea-Tac jets visually. Akers replied that this hadn’t been necessary for years previous, and that jets were being rerouted even when no adverse weather interfered.

Eventually the jets stopped crossing into the valley. FAA spokesman Kenitzer says the agency “corrected” the routing after “discovering” it had somehow strayed off course.

“It takes a lot to get the FAA to respond,” says Magnolia’s Robert Bismuth, a longtime private pilot himself. “The FAA has two mandates, safety and commerce, and no mandate about anybody on the ground. It traditionally hasn’t responded to noise and pollution concerns. If you want it to, you have to involve the congressional delegation.”

That’s what worked for Magnolia. In 2009 the FAA proposed lowering the Class Bravo “floor,” the minimum altitude for incoming jets, from 3,000 to 2,000 feet. In familiar fashion, it convened public meetings in Tacoma, Burien and Everett, but none in Seattle where the effects would be most severe.

Bismuth got McDermott and Sen. Patty Murray, both on committees overseeing the agency, to write letters. And he played the safety card: This would drop the floor for the Lake Union seaplanes and other “uncontrolled” aircraft that fly below the jets to just 500 feet. Besides consigning Magnolia and Queen Anne to noise hell, this would come too close to hilltop water and communication towers. The FAA conceded the safety issue and dropped its plans.

Beacon Hill doesn’t hold that trump card, but it may be able to play another: the National Environmental Policy Act, which bars environmental discrimination against poor and minority communities — the sort of neighborhoods that wind up under flight paths all across the nation.

That could be a much uglier fight. “To give the FAA credit, they turned around and worked with us,” says Bismuth, who’s shared his experience with the Southeast Seattleites. “I think they created a very antagonistic relationship with Beacon Hill, and they’ll pay for it.”

Meanwhile, the Port, the good cop, is trying to better its relationship. On Wednesday Sea-Tac’s managing director, Mark Ries, and Stan Shepherd will meet with the Quieter Skies Task Force — on Beacon Hill.

The author lives in Southeast Seattle, but blissfully outside the jet noise path.