While Boeing’s leadership scrambled to contain its latest crisis — following the in-flight door plug blowout on an Alaska Airlines 737 MAX 9 — top executives at Airbus confidently laid out the rival’s success in 2023 and its dominance of the commercial airliner business.

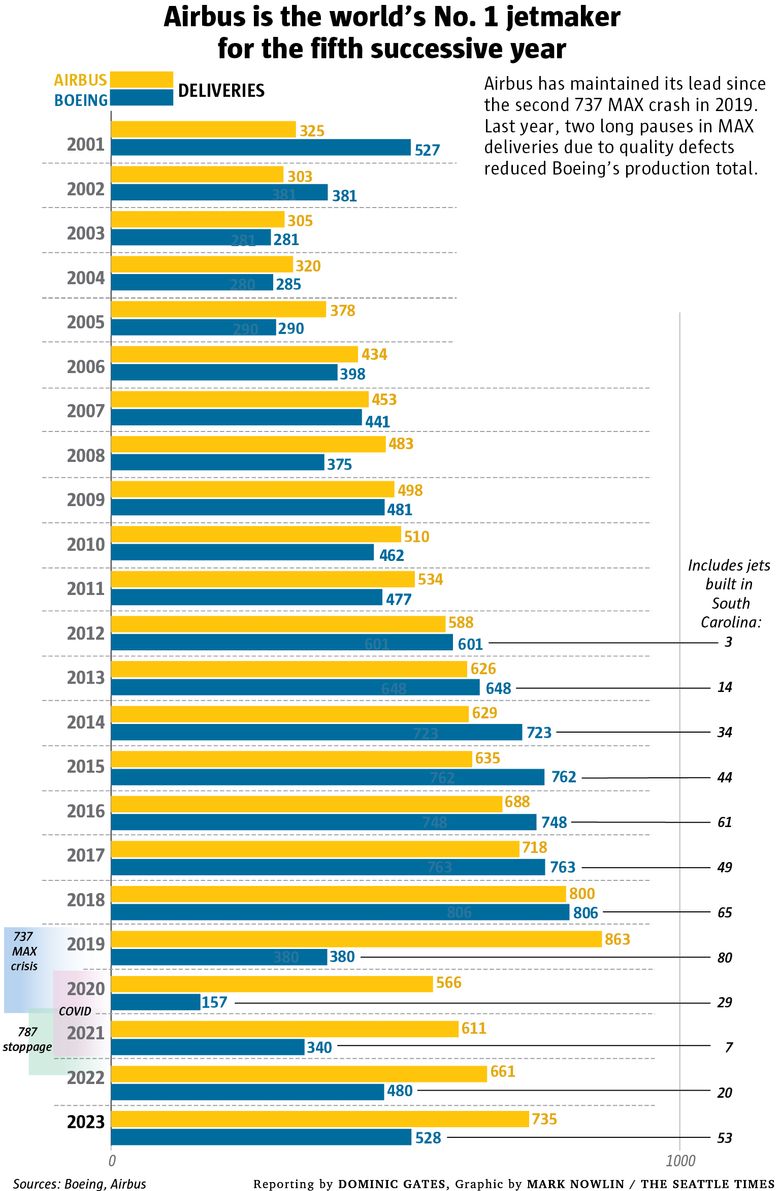

The data on last year’s jet orders and deliveries released by both manufacturers shows Airbus was the world’s No. 1 airplane maker for the fifth straight year and pulling away from its U.S. competitor.

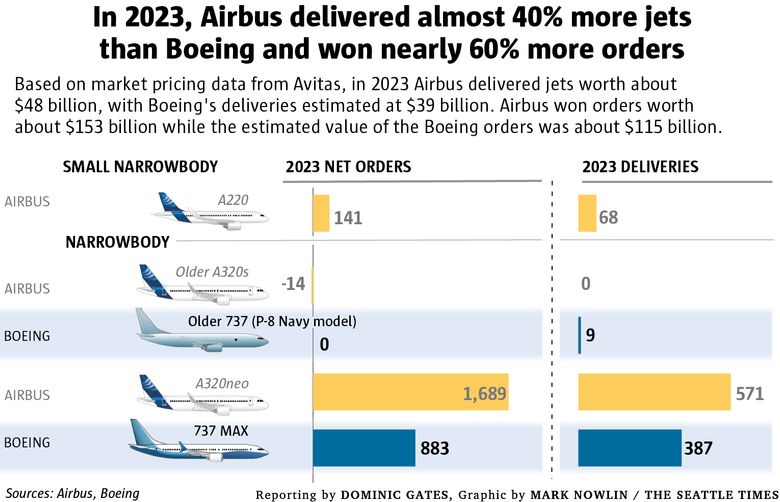

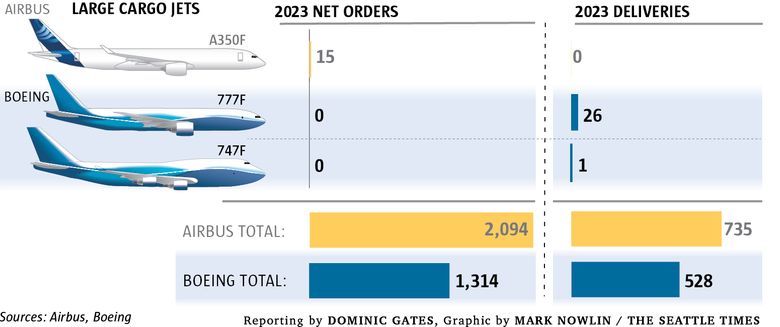

Airbus delivered 735 commercial jets last year, compared to Boeing’s 528. And Airbus won almost 2,100 net orders, a new record, versus slightly over 1,300 for Boeing.

About 1,700 of those Airbus orders were for its wildly successful A320neo and A321neo jet family. That’s nearly twice the orders Boeing won for its competing 737 MAX jets.

That data combined with the new sense of crisis at Boeing has produced a bleak outlook among observers of the company.

“I cannot see how Boeing can continue like this,” said longtime industry expert Adam Pilarski, of aviation consulting firm Avitas. “They are getting killed.”

Throughout last year’s series of quality lapses and production setbacks, Pilarski — who is personally close to many top executives and engineers within Boeing — remained one of the industry figures most staunchly positive about the company.

In an interview, he said the Alaska Flight 1282 debacle was the last straw for him and many inside Boeing.

“Boeing has been outplayed for a number of years and it looks worse and worse,” he added. “There’s no great hope. There’s no new leadership.”

“There’s a high probability Dave Calhoun will not survive long as CEO,” Pilarski said Friday.

In the wake of the Alaska Airlines close call, Ron Epstein, an aerospace engineer and Bank of America equity analyst, also questioned the viability of Boeing’s current leadership.

“We would not be surprised to see regulators, investors and customers push for a turnover in the ranks of senior management and the Board of Directors,” Epstein wrote in a note to investors.

Sash Tusa, a lead aviation analyst with London-based research firm Agency Partners, said via email the stark and growing imbalance in favor of the European jetmaker in the 2023 performance data offers little hope of a Boeing recovery.

“Based upon orders and backlogs, it is incredibly hard, mathematically all but impossible, to see Boeing getting back to No. 1 again, absent a MAX-type massive problem at Airbus,” Tusa wrote.

Airbus confident in growth plans

As Boeing CEO Calhoun struggled to deal with the outrage over the Alaska Airlines incident, he made few public appearances. He gave one interview to CNBC and Boeing posted some excerpts from remarks he made at town hall meetings with employees at both Boeing and Spirit.

“I have confidence in Boeing. I have confidence in the airplane, and I have confidence in you,” he told the employees in Renton. “Be aware of everything around you and pay attention to every detail that matters.”

Boeing’s management has worked largely behind closed doors, focused entirely on the crisis, searching for answers and fixes that could reassure regulators, airlines and air travelers. Awaiting the outcome of an investigation, publicly the company has issued only terse written statements.

Asked for its responses to Airbus’ dominant year in 2023 and to the potential impact the Alaska Flight 1282 incident will have on that rivalry in the year ahead, Boeing declined to comment.

Spokesperson Bobbie Egan said that until company earnings are reported later this month “we are limited in what we can say.”

In stark contrast, Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury and the company’s new Commercial Airplanes CEO Christian Scherer held a news conference on Jan. 11 in Toulouse, France, to tout the company’s 2023 performance.

The Airbus executives exuded confidence, took questions easily, and spoke of accelerating production and plans for new planes in the 2030s. For the Airbus leadership, clearly the present looks very good and all eyes are on the future.

While Scherer called last year’s production and sales results “pretty exceptional,” Faury said Airbus production is on track to meet much more ambitious targets.

Growing demand

With air travel now fully back after the COVID downturn, demand for jets is at record levels while supply from the world’s two major manufacturers is still well below pre-pandemic levels. So Airbus is gearing up.

From delivering in 2023 an average of about 48 A320neo family jets per month, Airbus projects reaching 75 per month in 2026.

Between Hamburg in Germany, Toulouse in France, Tianjin in China and Mobile, Ala., Airbus currently runs eight final assembly lines for those narrowbody airplanes and by 2026 will add two more lines, one in Tianjin, another in Mobile.

For the widebody A350 jets, which averaged just over five deliveries per month last year, the 2026 target is 10 jets per month.

For the small narrowbody A220 jet, against which Boeing has no competing airplane and that averaged nearly six deliveries per month in 2023, the 2026 target is 14 per month.

“We are in a steep ramp-up on all programs,” Faury said.

In the narrowbody jet market, the Airbus lead looks unassailable.

Deliveries of the largest and most expensive jet in that category, the A321neo, in 2023 made up well over half of all Airbus narrowbody deliveries and that share is growing as airlines look to put the jet on long routes.

In the second quarter this year, Airbus expects to deliver the first of a new extra-long-range model, the A321XLR. It’s already taken orders for 550 of those, which airlines will use on international routes instead of more expensive widebody aircraft.

“That’s a game-changing aircraft that will rewrite long-haul travel from this year onwards,” Scherer said.

Boeing has nothing to compete with the A321neo, never mind the XLR version.

But could Airbus be accelerating too fast? As it pushes production rates up, is it risking a setback similar to Boeing’s?

After all, Spirit AeroSystems, which was behind several quality lapses that affected Boeing production last year and installs the door plug that blew out on Alaska Flight 1282, is also a major supplier of parts to Airbus.

Tusa in London said Airbus has over many years benefited from reasonably steady production rates, compared to Boeing’s tendency toward wild rate swings and cutting production drastically during downturns.

“More constrained by European labor laws,” and supported by European governments to sustain employment, Airbus is “far more focused on production stability,” Tusa said.

At the news conference, Faury said Airbus is “monitoring very closely everything that comes out of the ongoing investigation” of the MAX flight incident.

“We will continue to put a lot of priority, a lot of attention, on quality to serve safe airplanes,” he said.

Can Boeing hold onto its advantage in big jets?

Using market pricing data from Pilarski’s firm, Avitas, The Seattle Times estimates the dollar value of the 2023 commercial jet orders at $153 billion for Airbus and $115 billion for Boeing.

The jet deliveries from Airbus are estimated to be worth about $48 billion compared to about $39 billion for Boeing.

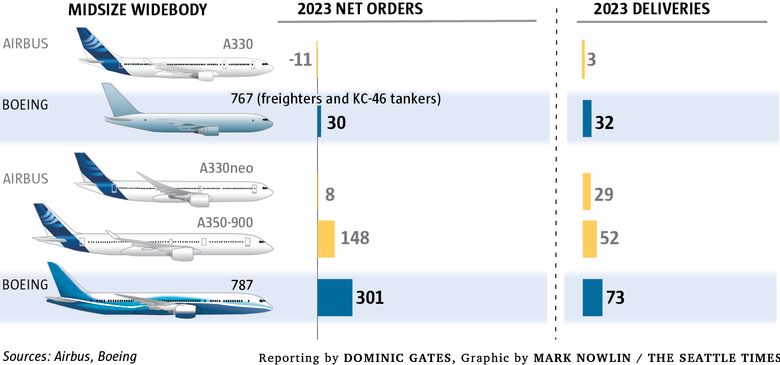

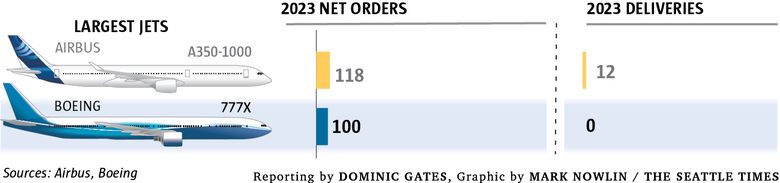

One spark of hope for Boeing in the data is that the U.S. jetmaker managed to hold onto its historical lead in the larger widebody market.

Boeing delivered 132 widebody aircraft to 96 for Airbus. And Boeing sold 431 widebody jets to 278 for Airbus.

This was mainly due to the success of the 787 in both new orders and deliveries.

However, Pilarski said that segment of the market could slip away from Boeing, too.

The Airbus widebody A350 is gaining momentum and achieved a huge win this month when Delta ordered 20 of the biggest model, the A350-1000.

Delta already operates 28 of the smaller A350-900s and by the end of the decade will be flying 60 Airbus A350s internationally.

“The A350-1000 will be the largest, most capable aircraft in Delta’s fleet,” said Delta CEO Ed Bastian.

Clearly, Delta wasn’t prepared to wait for Boeing’s forthcoming giant jet, the 777X. Certification of the 777X passenger version is long delayed, and the jet is not expected to enter service until late next year.

In addition, Airbus previously did not compete in the widebody freighter market. Two years ago it launched the A350F freighter, which now has 50 orders.

A new global aviation carbon emissions standard threatens to force the shuttering of Boeing’s current 767F and 777F widebody freighter programs four years from now. Neither of those jets won any new orders last year.

That means in the immediate future, widebody cargo jet sales campaigns may be more even battles than in the past, with the freighter version of Boeing’s 777X competing against Airbus’ A350F. The 777X cargo version isn’t due to enter service until 2027, two years after the A350F.

The 777X has to have a successful debut if Boeing is to stem the A350’s momentum.

Boeing “better get their 777X finally on time and become a spectacular plane,” said Pilarski. “Otherwise I don’t see how they can survive.”

A vision for the future?

Despite pressure from the success of the A321neo, Calhoun last year declared Boeing won’t launch an all-new airplane anytime soon, saying the company must first focus on trying to get production back on track and much-needed cash coming in.

In contrast, Airbus’s Scherer outlined a vision for the 2030s.

“The next decade will be a defining period for our company, with a hydrogen-powered airliner and a very fuel-efficient successor to the A320 program,” Scherer said at the news conference.

For Pilarski, Calhoun’s stance was acceptable as long as his strategy was achieving its goal. The Alaska Flight 1282 incident suggests it is not.

Calhoun “told the world, we’re not thinking about the future until we fix what we are doing now,” Pilarski said. “It turns out, he doesn’t know how to fix the present.”

After the MAX production setbacks last year, Boeing had hoped for a fresh start in 2024.

Things looked to be headed up toward the end of 2023, with big sales wins in November at the Dubai Air Show and 67 jet deliveries in December, the highest monthly total for the year.

But the hope for a turnaround has now been set way back.

The Alaska in-flight incident has grounded MAX 9s, will inevitably slow future production because of the need for extra inspections, and could cause the FAA to delay certifying the final two MAX models, the MAX 7 and MAX 10.

Boeing’s customers, the airlines, are hurting from the grounded airplanes. The trust of both the regulators and the traveling public is broken.

From his contacts inside the jetmaker, Pilarski said he knows that “there are more and more people at Boeing who are very, very unhappy.”