Boxed in by loud vehicles, plane traffic, and their fumes, its residents just want to breathe easy.

By Hayat Norimine 12/19/2017 at 8:00am Published in the January 2018 issue of Seattle Met

From the rain-soaked garden where a Spanish-speaking mother and her children sat on an early November morning, whiffs of rose and lavender reached the door of social justice nonprofit El Centro de la Raza. Inside, bunting hung from the ceiling for Dia de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, honoring friends and family members who have died. But an exhibit mourning a different kind of death was displayed among them. Two maps on a poster board tracked flight arrivals and takeoffs from Seattle-Tacoma International Airport; miniature red and blue airplanes dangled from the branches of a small plastic tree. We can’t focus, complained a flyer signed by “the Beacon Hill community.” We can’t sleep.

“Our dearest Silencio, Peace y Quiet,” the eulogy continued, “we miss you so much.”

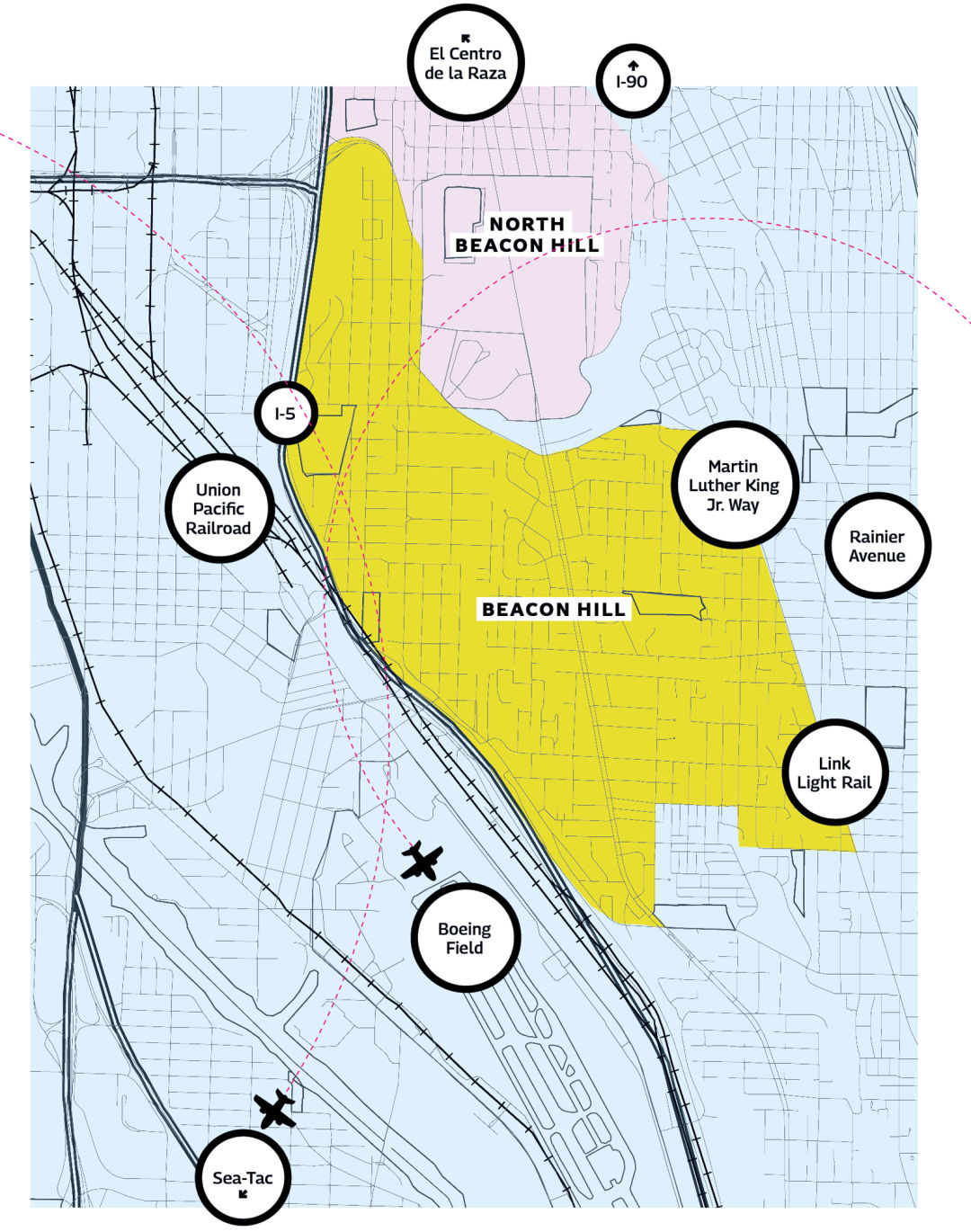

The Southeast Seattle neighborhood, one of the most diverse in the city, is boxed in by traffic. Two major arterials, Rainier Avenue and Martin Luther King Jr. Way, run east. Head west and you’ll hit Interstate 5; Interstate 90 is north. And, on average, every three minutes during peak periods, an airplane roars overhead. Seventy to 80 percent of the planes that land at Sea-Tac fly a mere 2,500 to 3,000 feet over Beacon Hill.

“Some days you feel like, Are we at war?” says Maria Batayola, chair of the Beacon Hill Council.

Rising demand for more Sea-Tac flights has led to even more sound. Between 2012 and 2016, aircraft landings increased by a third. The Port of Seattle estimates the number of passengers who travel through Sea-Tac will grow from 47 million to 66 million by 2034. Residents fear that, between increasing traffic congestion and the city’s expanding transit infrastructure, they will have to bear the brunt of unintended consequences.

They have reason to worry. While pollution in the United States has improved with stricter regulations, some of us are breathing cleaner air than others. A recent study by University of Washington professor Julian Marshall showed people of color are exposed to more pollutants than white Americans. But Marshall wasn’t anticipating how much more—the exposure rate for people of color was nearly 40 percent higher, a number that had barely changed in the 10 years prior.

And, even to Marshall’s surprise, money made no difference—the imbalance exists regardless of income. Rich people of color still breathe dirtier air than rich white people. “It’s the part that stares me in the face every day when I look at this,” he says.

Nonwhites are 2.5 times more likely to live in areas with high levels of nitrogen dioxide.

Batayola and others have long suspected that Beacon Hill is disproportionately affected by the air and noise pollution from the planes. So in 2016, Batayola successfully applied through El Centro de la Raza for a two-year, $120,000 environmental justice grant from the Environmental Protection Agency. She and Roseanne Lorenzana, a former EPA toxicologist and UW public health professor who lives in Beacon Hill, have used some of the money to start collecting data on air pollution exposure. After presenting the results to their neighbors at a series of community meetings, they then asked for ideas to improve their environment. The brainstorming sessions lasted months, and required the help of six translators; about half of Beacon Hill residents are Asian or Pacific Islander, and 44 percent are foreign born. In the end, though, they drew nearly 300 suggestions. Batayola and Lorenzana used them to plot out a community action plan.

Beacon Hill residents can’t easily tap federal aid because they don’t live right by the airport. But they think they may have a right to the government’s help mitigating noise and emissions.

Title VI prohibits racial discrimination for any program that provides federal financial assistance. If the national airport mitigation program refuses to help minority neighborhoods impacted by aircraft emissions, the center could argue it’s violating federal law.

“How do we get to say, ‘Wait a minute, we’re unduly burdened by this’ ?” Batayola says.

She was 14 years old when her family moved from the Philippines to the Central District, but she always wanted to live in Beacon Hill.

She wanted a place where she could feel welcome and share a community with other residents who looked like her—“a welcoming place,” she says, where she wanted to raise her kids. She relocated there in her 20s and stayed for 32 years before leaving for Bellevue when she married. Still, she spends several days a week volunteering in Beacon Hill for the community she loves.

She thinks it’s worth standing up for a neighborhood that’s become a haven for so many people of color. They just wish the peace and quiet there would return.

“We promise to make things better,” pleads the flyer on display at El Centro de la Raza. “Please come back.”

Updated December 21, 2017. Rather than boost the number of passengers traveling through Sea-Tac, as the article originally stated, the Port of Seattle estimates an increase based on the growth of the region.