SEATAC — As massive clouds of smoke from wildfires throughout the region obscured the sky last week, SeaTac Deputy Mayor Peter Kwon filtered the air in his own home by attaching a furnace filter to a box fan and then duct-taping a triangular piece of cardboard over the gaps. When the air quality index (AQI) rose to 225 last week, Kwon said that his contraption reduced the living room to below 50 AQI.

The ultrafine particles from aviation and roadway traffic had long concerned Kwon, who lives about a half-mile from Seattle-Tacoma International Airport: While recent wildfires have forced residents across Western Washington to experience the hazards of poor air quality, Kwon and others who live in communities surrounding the airport say they’ll continue to face a year-round threat to their air from aviation-related pollution.

Three months ago, Kwon joined three other residents who had installed air monitors on their properties near the airport by placing one outside of his home. Their findings, documented in the citizen-gathered Purple Air Map, came as no surprise to him: “The air quality around the airport is not as clean as areas farther away,” he said.

He believes the addition of smoke pollution could form a toxic cocktail that would exacerbate respiratory diseases such as COVID-19. “One of the problems is that SeaTac has historically had poor air quality. So with the wildfires, the poor air quality has just skyrocketed,” Kwon said.

As wildfires become more common along the West Coast, residents of airport communities such as SeaTac, Burien and Des Moines fear they will be harder hit by pollution. In the future, cities under flight paths will need to become “smoke ready,” said Elena Austin, an assistant professor at the University of Washington’s department of environmental and occupational health sciences. “But they’re also going to have to develop ways to be resilient to the air and road traffic impact on their communities.”

Local politicians, residents, and researchers are working with airport communities throughout the nation to study the effects of air pollutants, as well as brainstorm solutions for homes and schools. For the Port of Seattle’s part, the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport has electrified hundreds of ground vehicles and encouraged Uber and Lyft to reduce carbon emissions by switching to hybrid or electric cars.

“We recognize that the local communities have the impact from the airport,” said Perry Cooper, Seattle-Tacoma International Airport’s media relations manager.

Still, concerned residents say more drastic changes are needed to address the potentially harmful effects of particles seeping into windows and doorways.

“The impact that’s difficult for people living near the airport is that they already experience and perceive poorer air quality,” said Austin. “So that creates challenges in a search for safe and healthy spaces.”

Wildfire smoke particles are much larger than pollutants emitted from airplanes. For that reason, the aircraft ultrafine particles are more likely to infiltrate the indoors, said Austin, adding that smoke still seeps in.

It is difficult to measure the combined effects of various pollutants during wildfire seasons. Air quality index monitors mostly measure the largest particles in the air, which is the wildfire smoke, said Austin, while ultrafine particles from aviation and ground traffic do not influence the value.

Still, the particle pollution has widespread impacts. SeaTac ranked 14 for 24-hour particle pollution out of 216 cities in The American Lung Association’s State of the Air report. Exposure to air pollution has been shown to cause “delays in psychomotor development, lower IQ in elementary school children, increased risk for autism, greater anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit related problems during childhood,” cited a recent state Department of Health summary of health research on ultrafine particles.

Meanwhile, SeaTac has among the highest percentage of positive COVID-19 cases in the county, according to Public Health – Seattle & King County, at 2,070 per 100,000 compared to King County’s 964 per 100,000.

Environmental advocates argue that the area’s shorter life expectancy compared to King County’s average indicates that residents are living in unhealthy conditions.

“We have a perfect chemical zoo of potential respiratory problems,” said former Burien City Councilmember Debi Wagner. She’s now a member of the Burien Airport Committee, where she advises the City Council on matters concerning the airport, as well as the nonprofit Quiet Skies Coalition.

Wagner started researching airport emissions about two decades ago, when she said she awoke in her quiet Des Moines home to a “war zone” as hundreds of jets suddenly flew overhead every day.

“As wildfires are becoming the norm, airport communities need mitigation more critically than other areas because we’re living with a much lower quality of air and life,” said Wagner, now a Burien resident.

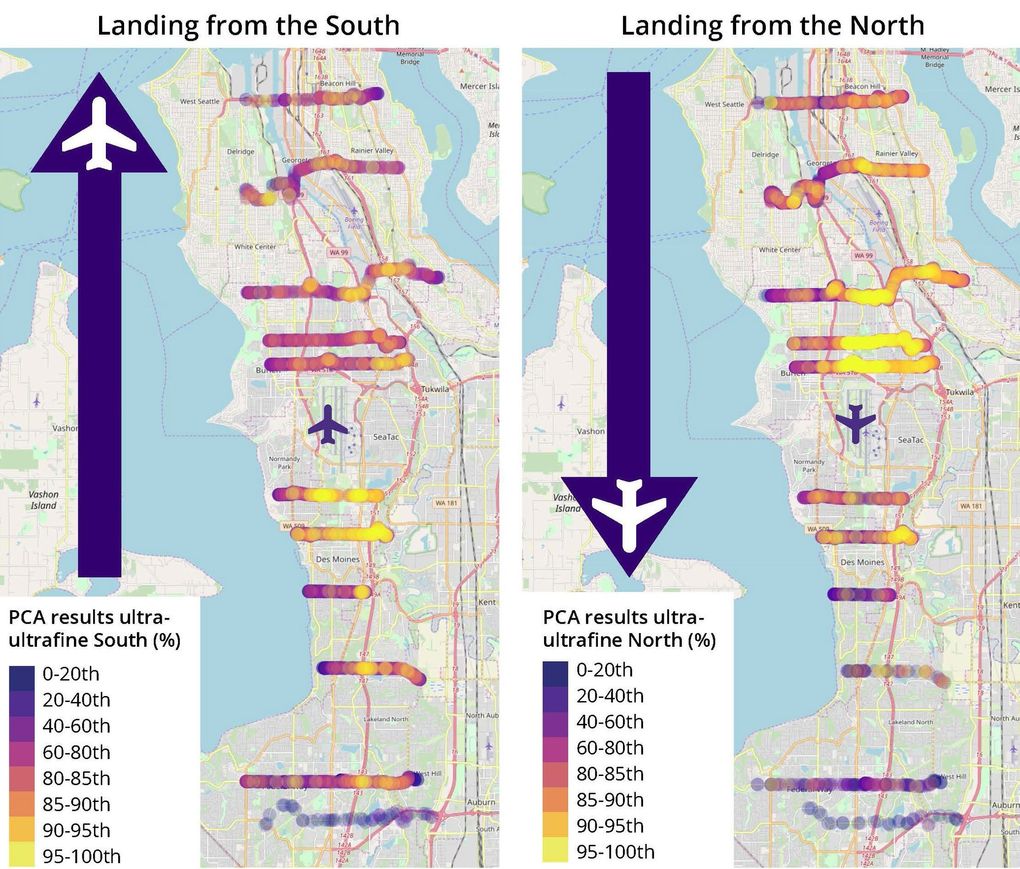

About three years ago, SeaTac lobbied the State of Washington to fund an air quality study in the vicinity of the airport. That led to a two-year UW study co-authored by Austin and released last December, funded by the Washington State Legislature and the Port of Seattle. The study showed that ultrafine particles emitted by aircrafts impact communities under their flight paths.

UW plans to launch a second phase of the study that will rely on drones to measure the effect of vegetation on ultrafine particles. Researchers hope the study will offer insight on the role of urban planning programs that use greenery to mitigate particulate air pollution.

Last year, the state Legislature voted to create another commercial airport in Washington, which Kwon hopes will reduce layover flights at Sea-Tac that contribute to air pollution. “The reality is that Sea-Tac airport is so small: There’s a physical size limit of the airport because it’s surrounded by developed land,” he said.

The SeaTac City Council is also working with state Rep. Tina Orwall, D-Des Moines, to bring air filters into schools, and they later hope to secure funding for filters that will be installed in residents’ homes, Kwon said.

Orwall plans to tour Burien’s Highline Public Schools this week, she said. She’s also reached out to representatives in Eastern Washington struggling with fires to gain insight on how residents in those areas minimize exposure to pollution.

While the Port of Seattle’s efforts to mitigate emissions have largely focused on noise reduction and clearing waterways, some initiatives in recent years have been aimed at reducing air pollution on site. The greatest reduction in aircraft emissions has come from preconditioned air and ground power at each of the gates, which enables the small engines in the back of the aircraft to be powered off. Additionally, Port commissioners are advocating for widespread use of aviation fuels derived from renewable sources such as municipal waste, and oily seeds. The sustainable fuel emits up to 80 percent less carbon than fossil fuels when burnt, said the Port.

“The Port of Seattle’s commission has made support of the low carbon fuel standard their number one legislative priority, because not only would it incentivize those fuels and make them cheaper, it would make them more widely available in those communities,” said Stephanie Meyn, Seattle-Tacoma International Airport’s climate program manager.

For SeaTac resident Kent Palosaari, a marriage and family counselor, the airport’s initiatives have come too late for him to see a future in the city. He says the pollution has impacted his health to such an extent that in October he’ll move his family to Edgewood.

But the impending move hasn’t stopped Palosaari from remaining interested in the air quality surrounding the airport. Over the past 1 1/2 years, Palosaari has regularly tracked the pollution in his area using a handheld air quality monitor.

His pet project has inspired him to act. Palosaari spearheaded a forthcoming virtual solution summit for airport communities around SeaTac and Boston, and he plans to launch a nonprofit to push for healthier conditions in cities under flight paths.

He is passing his advocacy down to his children, who sometimes accompany him on his circuits to monitor the area’s air quality. As wildfire smoke billowed into his community, he brought his children to Seacrest Park to film the haze that had consumed the marina. On camera, his 9-year-old daughter shared an anecdote about her classmates running to the nurse’s office after recess to fetch their inhalers.

As Palosaari panned the smoke-filled sky, he told his children: “You know, there’s going to come a time when this is no longer an exception, it’s the rule.”