It’s tricky to point at a lack.

But in journalism, what’s left unsaid — whether it was overlooked or ignored — can be as corrosive as a falsehood.

In this edition of the A1 Revisited project, we’ve taken a hard look at how The Seattle Times covered Native protests at the Fort Lawton Army base in 1970 — and discovered a profound disconnect between the newspaper and the community it was trying to cover.

In missing the context, we missed the story.

Throughout March 1970, Native activists staged a series of dramatic protests at Fort Lawton, a nearly 1,000-acre military installation in Seattle’s Magnolia neighborhood — climbing over its fences, establishing an occupation camp at its front gate — to secure some land the federal government was trying to give away. Those protests birthed the nonprofit United Indians of All Tribes, and its headquarters at the Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center. But The Seattle Times didn’t convey the gravity of those events.

“The Seattle Times was really behind the times when it came to reporting all this,” said Randy Lewis, a Wenatchi/Methow elder from the Colville Confederated Tribes. “What we were doing was viewed as a poor man’s civil rights action. They didn’t go after why we were doing it, what drove us to that action. People might’ve been more supportive and understanding if it hadn’t been played off as some trifle.”

The events building up to the protests were many and complex: increasingly violent treaty-rights conflicts in South Puget Sound; a federal “termination” campaign to dissolve tribes and move Native people to cities; and the overtaxed volunteer networks, led by Indigenous women, to help this newly displaced, rapidly growing Urban Indian population.

The initial front-page coverage, by contrast, shines most of its light on the presence of movie star Jane Fonda and the amused reactions of foreign reporters, one belittling her as a “third-rate Vanessa Redgrave.”

The protest

On March 8, 1970, around 100 Native activists and their supporters scaled the fences and bluffs surrounding Fort Lawton — a waterfront Army base, most of which is now Discovery Park.

They had come to stake a land claim.

It was a long time coming. “This was more than ‘some Indians just jumped a fence, put up a tipi, and waited for the police to come,’” said Joshua Reid (Snohomish), associate professor of American Indian Studies at the University of Washington. “This was part of a long-running effort to help ameliorate the impoverished conditions of Native families.”

Six years earlier, the U.S. military had announced plans to deactivate the 70-year-old fort but keep around 15% of the property. The city wanted the leftover land for a park; the wheels started turning. Groups like the Sierra Club and the Magnolia Club (representing the wealthy neighborhood bordering the fort) formed a pro-park committee while U.S. Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson pushed a bill through Congress that would transfer the land from the federal government to the city at little or no cost.

Native leaders had also been making plans. They’d asked for a piece of that soon-to-be-surplus property through official channels, but had gotten nowhere. “We were essentially saying: ‘You want another park, huh?’” Lewis recalled. “‘You’ve got plenty of goddamned parks! We don’t have anything!’”

A campaign to secure social services might not have seemed especially thrilling or urgent to inattentive outsiders, but they were desperately needed. Partly due to federal relocation policies, Seattle’s Native population had grown sixfold between 1950 and 1970 (the city’s overall population grew by 13.5%) but the resources they’d been promised were scant. The Bureau of Indian Affairs had pledged help with jobs and housing — but often gave just token assistance, leaving people stranded and struggling. Medical care was a three-days-a-week clinic staffed by volunteer doctors and nurses.

Whitebear, who died in 2000, wrote a 1994 essay recalling how Native organizers “began making overtures to the city’s leaders, requesting that a portion of Fort Lawton be set aside.” The city suggested they talk to the BIA — but the agency was lukewarm at best. Regional director Dale M. Baldwin said they could find the programs they were looking for in California and New Mexico.

Ramona Bennett, who’d later become chair of the Puyallup Tribe, recalls typing up a detailed land-use plan with Whitebear and presenting it to Sen. Jackson while he was in town. “We were very serious and expected to be taken seriously,” she said. “They just blew us off.”

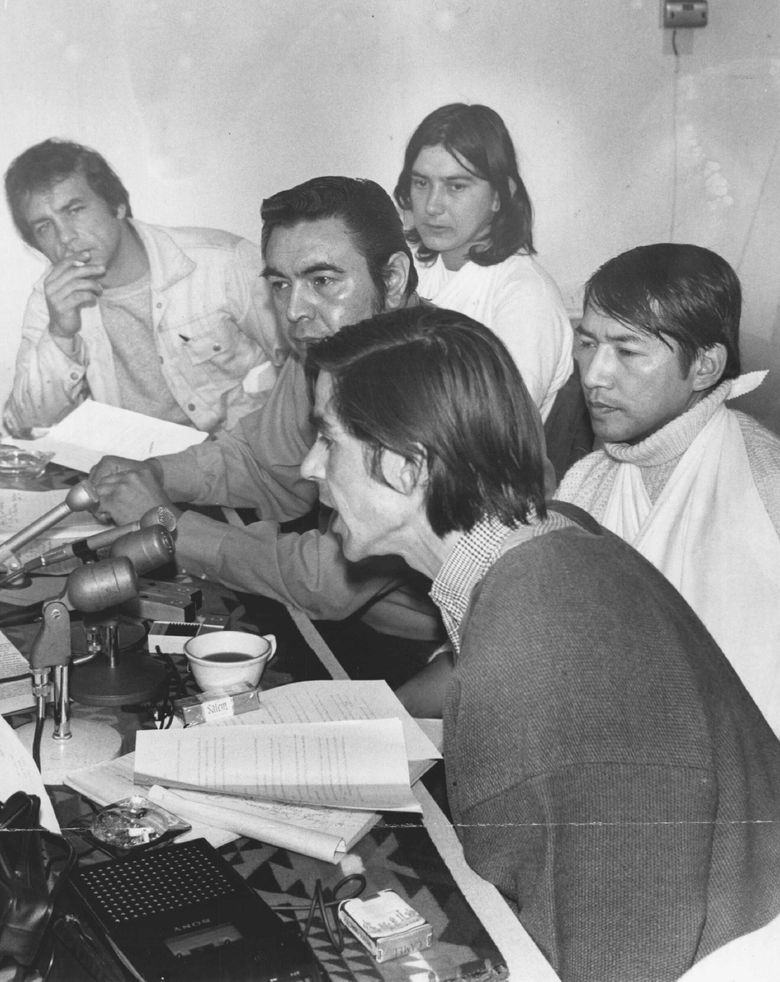

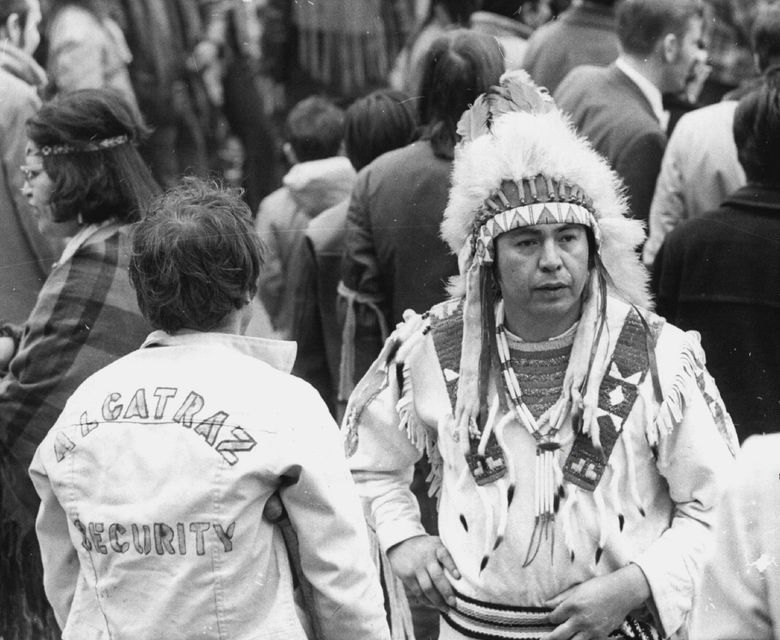

Meanwhile, Bennett, Sid Mills and others visited Alcatraz Island in California, which Native activists had been occupying since November 1969. That ongoing protest, Mills said, was more symbolic than practical: “Alcatraz is an idea, not an island. That’s what leader Richard Oakes said.” But it was also a proof of concept. In Seattle, asking permission and filing paperwork hadn’t achieved anything. Perhaps an occupation would.

Non-Native activists also showed up, including members of the Black Panther Party, local Latino activist Roberto Maestas and actor and activist Jane Fonda.

While Fonda and others climbed the fort’s fences, another team scaled its seaside bluff with tipi poles and camping gear, assembling a makeshift settlement before MPs found them. The scene became a scuffle when one of the MPs shoved Mills, who punched back, but most demonstrators went limp, forcing MPs to carry them.

Within hours, over 70 activists had been detained, then expelled from the base. A few of the men — including Whitebear and a car mechanic named Leonard Peltier (Turtle Mountain Anishinaabe) — were beaten in the stockade. Mills said he left with “a fat eye, a fat lip” and a dislocated shoulder.

“I guess we should’ve been intimidated, but apparently we didn’t have a brain among us!” Bennett joked. “We just recharged our batteries.”

They’d be back soon.

The Coverage

The next day’s front page of The Seattle Times covered the events in two short, incongruously lighthearted stories: “Jane Fonda Gripes About Detention at Fort Lewis” and “Indian ‘Attack’ on Fort Fascinates World Press.” (After being ejected from Fort Lawton, Fonda and a few others drove to Fort Lewis.)

Between them, the two stories contain seven mundane quotes from Fonda (“I asked at one point to make a call to my lawyer”), six from amused European reporters calling The Times’ newsroom (“‘Tell me,’ he continued urbanely, ‘Do you have an Indian problem out there?’”) and none from Native activists, nor a mention of what they were trying to achieve.

“It was treated as a joke: ‘Oh, those crazy Indians are at it again!’” Bennett said. “They didn’t recognize that job training and housing were critical needs. Just like Sen. Jackson blew us off, so did the press.”

A longer story on Page 11 (“Indians ‘Invade’ Army Posts”) is more serious, quoting Whitebear and others, and includes allegations of the beatings.

The language of “attack” and “invasion” peppers the coverage, but activists say those terms didn’t originate with them.

Where did they come from? Perhaps the movies.

“Everybody writing about it had already imbibed idealistic images of John Wayne Westerns, Indians invading forts,” said Kent Blansett (Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Shawnee and Potawatomi), a scholar at University of Kansas. Eventually, he explained, protesters came to adopt those words — they were generating attention that, until then, had been elusive.

“All press is good press at this point,” Blansett said. “Do you accept that there’s bias? Of course! But you need the message out there.”

The Seattle Times’ coverage, while not wholly inaccurate, fails to communicate the context and stakes. A purportedly sympathetic editorial on March 10 bemoans the plight of “the most neglected Americans” but dismisses the protests as a “faddish … copycat act” based on Alcatraz that “no one is likely to take seriously.”

This was not out of character in those days for The Times, which had covered some of the fishing-rights struggles in South Puget Sound, but was largely disconnected from Native American issues — particularly the growing Urban Indian population.

A search of The Seattle Times’ archives between 1940 and March 8, 1970 — the day of the first protest — turned up eight mentions of “Urban Indian.” Five of those were very brief stories, some about national affairs. A search for articles mentioning federal “termination” policy turned up 22, but only three were substantive, locally reported stories.

The newsroom hadn’t strongly engaged with Native communities and concerns — so couldn’t begin to make sense of an event like Fort Lawton.

What The Times missed

A confluence of forces led up to the protests, a history too rich and nuanced to treat comprehensively here.

Besides the occupation of Alcatraz and the long-running fishing-rights struggles, Seattle activists had also been forging multiracial coalitions — which helps explain why Black Panthers were climbing fences at Fort Lawton and Native activists supported the occupation of a Beacon Hill school in 1972, which became El Centro de la Raza community center.

But one of the most significant — and least understood — factors was the federal termination and relocation policy.

In 1949, a presidential commission called for the “complete integration” of Native people “into the mass of the population.” Congress and the BIA followed the directive, “terminating” over 100 tribes and bands, facilitating sell-offs of Native land and encouraging people to move off reservations and into cities, while promising job training and other assistance when they got there.

That assistance was meager.

“A lot of families were just abandoned by the government once they brought them into the city,” said Ramona Bennett, who joined the American Indian Women’s Service League in 1966. She recalls another volunteer, Hattie Kauffman (Nez Perce), saying: “When you’re cold and hungry on a reservation, you can always cut some wood to keep warm and hunt to feed your family. But if you’re cold and hungry in the city, you’re just cold and hungry.”

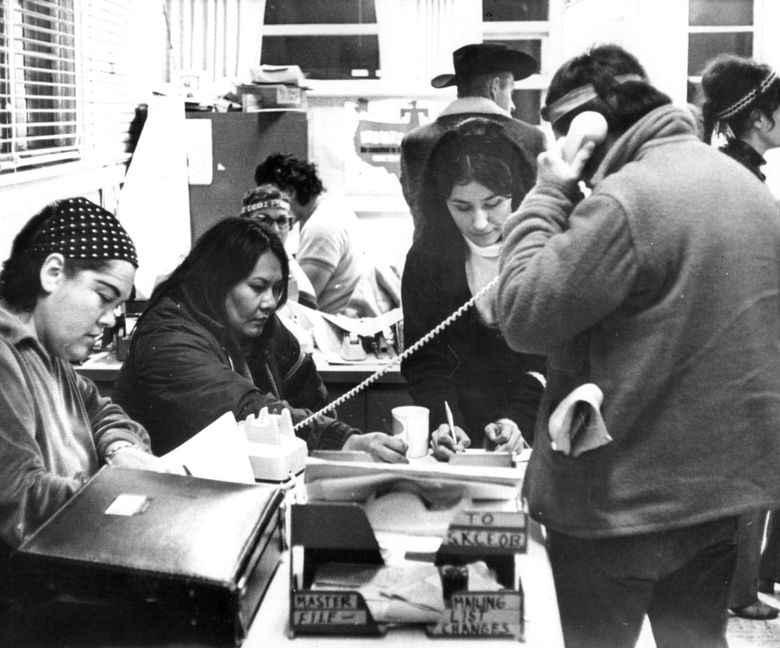

In 1958, seven women — including Pearl Warren (Makah), Ella Aquino (Lummi) and Adeline Garcia (Haida) — formed the Service League to help. The group covered a lot of ground: emergency food and clothing, social and cultural events, raising money and visibility with salmon bakes, establishing the modest Seattle Indian Center in Belltown, publishing the Indian Center News and much more.

“In hindsight, you could say they wrote the book on community development,” said Jackie Thomas Swanson (Muckleshoot), a Service League volunteer from 1964 to 1975. “They created this home away from home where you could have a cup of coffee, sing a song and not feel so lonely.”