Editor’s note: This is an edited excerpt from the new book “Flying Blind: The 737 MAX Tragedy and the Fall of Boeing” by Peter Robison.

LATE IN THE SUMMER of 2000, Boeing Chief Executive Officer Phil Condit came home and confided in his wife, Geda. “I think we need to move the corporate headquarters for fundamentally strategic reasons,” he said, in his own recollection. Professorial and accomplished — an aerospace engineer who held a patent for a type of flexible wing called a sailwing — Condit had long been seen as among the most technically brilliant of a technically brilliant workforce.

But in the previous year, a bruising 40-day strike by his fellow engineers — who saw his strategic reasoning as fundamentally flawed — had shown the deep fissures at a proud company. The 1997 acquisition of McDonnell Douglas had brought hordes of cutthroat managers, trained in the win-at-all-costs ways of defense contracting, into Boeing’s ranks in the misty Puget Sound. It was “hunter killer assassins” meeting “Boy Scouts,” in the words of a federal mediator who considered the partnership doomed.

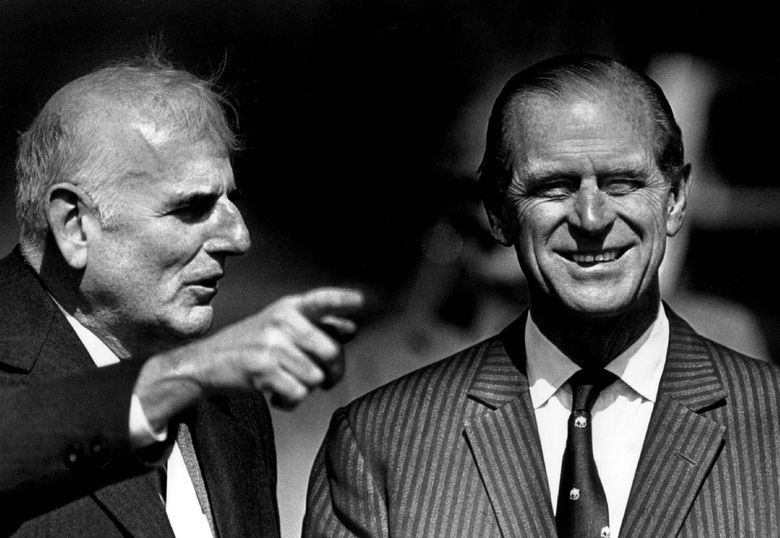

The new managers, led by former McDonnell Douglas chief Harry Stonecipher, drove the message that cash flow and profitability — delivering returns to shareholders — had to become Boeing’s top goal. To the engineers, it was all the more dispiriting because Boeing had only recently developed an impressive new aircraft called the 777 under the rallying cry “Working Together,” breaking budgets to produce what’s still considered one of the safest commercial airliners ever to fly.

Condit had hired Ted Hall, a McKinsey and Company consultant, to discuss how to manage the competing demands of his sprawling company under his leadership, by now a giant in space and defense as well as commercial jets.

It was the kind of big-picture planning Condit relished. General Electric famously had its headquarters in Fairfield, Connecticut, separate from the diverse businesses it owned. As he and Hall talked, Condit became convinced that Boeing needed a similar structure. “Headquarters is supposed to be thinking longer-term: Where are markets going, have we positioned the company correctly, are we developing the right people, what’s the compensation structure that we have? The kind of things that are not how-do-you-design-an-airplane stuff,” as Condit later recalled. “How do you avoid getting deeply engaged in the day-to-day activity, and ignoring those strategic things?”

On March 21, 2001, Condit stunned hometown Seattle, where Bill Boeing had built his first wooden float planes nearly a century earlier, with the bombshell that he’d be moving the headquarters. The news had been tightly guarded, so much so that Boeing hadn’t even told Seattle’s mayor, Paul Schell. “John, why didn’t you call?” the mayor plaintively asked John Warner, the high-ranking Condit lieutenant who had led the secretive new headquarters search.

Boeing set up a sweepstakes pitting cities against one another — much as fellow Seattle behemoth Amazon would do, to great fanfare and controversy, nearly 20 years later. It was a powerful statement of the ascendancy of the corporation. After seven weeks, with each of the contestants — Dallas-Fort Worth, Chicago and Denver — promising tens of millions in tax breaks, Condit climbed into his jet and had the pilots file three separate flight plans.

Finally, he announced, “We’re going to Chicago.”

The move meant more than a change in time zones. Boeing’s headquarters would be “a new, leaner corporate center focused on shareholder value,” the company’s statement said. The self-conscious emphasis on investors reflected a change within the company’s upper ranks, and especially in its top seat, that took hold in the first decade of the 21st century. Indeed, across America, the Reagan revolution a generation earlier had emboldened corporate leaders — none more than GE’s Jack Welch, who was admired by both Condit and Stonecipher. The business titans embraced the idea that any company has a single social responsibility: to increase its profits. They were rewarded with laissez faire trade, labor, tax and regulatory policies that maximized returns for shareholders, including themselves.

Where previous generations of Boeing leaders prided themselves on knowing everything about the aircraft they built — they were deeply engaged in precisely the “how-do-you-design-an-airplane stuff” — its new leaders were judged by their performance in meeting financial metrics: especially “return on net assets,” or RONA, which measures the ratio of net income to capital employed. In practice, the easiest way to make the number go up was by selling off manufacturing plants.

The financial wizards would prevail, hollowing out an iconic company that once stood as a model for innovation and profit. For a time, Boeing would even become a Wall Street darling, doubling down on stock buybacks that channeled cash to shareholders at the expense of other priorities, such as research and development. From 2013 to 2018, almost 80% of free cash went to buybacks, an innovation in financial engineering that had been enabled by a rule change of the Reagan-era Securities and Exchange Commission. From the vantage point of the present day, a disaster like that of the 737 MAX in 2018 and 2019 — a flawed flight-control system that caused the deaths of 346 people, cost tens of billions of dollars and squandered Boeing’s reputation for peerless engineering — would begin to seem not only tragic but inevitable.

BEFORE CONDIT LAID the groundwork for Boeing’s financial reinvention, its leader for much of the 1970s and 1980s was the crusty and demanding T. Wilson, who had been one of the first officers in the company’s union of engineers. After Boeing purchased McDonnell Douglas in 1997, while installing many executives from its former rival in top posts, the retired Wilson had a rueful verdict: “McDonnell Douglas has bought Boeing with Boeing’s money.” He told at least two of his former deputies that grooming Condit for the top job had been his biggest mistake.

In the messy turf battles following the merger, “Where’s Phil?” became the frequent refrain about their conflict-averse boss among executives at the Seattle headquarters. He spent the equivalent of 70 days a year in the air, much of it visiting Washington, D.C., or the company’s lavish new training center near St. Louis. He told reporters that his traveling would be easier from a more centrally located headquarters (oddly, casting shade on the thing that had made Boeing’s reputation, air travel) and that he’d have a “more global view of opportunities.”

The move to Chicago ultimately stemmed from Condit’s insecurities — his fear of conflict and his fear that investors wouldn’t recognize his attempts to remake Boeing without a dramatic flourish. “As long as we are side-by-side with commercial airplanes, the view always is that’s what we’re about,” he said.

The Boeing World Headquarters opened in 2001, 36 stories above the Chicago River in what used to be called the Morton Thiokol Building — named, ironically, after the infamous maker of the failed O-rings in the Challenger explosion. Condit’s old office had been in a gritty industrial strip of South Seattle, its windows looking directly onto the field where employees would one day test and fly the 737 MAX. Boeing’s new, supposedly “leaner” headquarters had 19th-century rugs, an antique French barometer topped with a carved eagle, a glass scepter and an English Regency gilt mirror among the objets d’art dotting its leather-and-wood executive suites. The white-columned hallway and wooden floors inlaid with oak and mahogany in the Office of the Chairman evoked a colonial gentleman’s estate.

THE BATTLE FOR Boeing’s soul would play out dramatically in the high-stakes decision-making that led to its first big endeavor of the 21st century, the 787 Dreamliner. The proposed plane would incorporate technological advances, like a lighter and stronger carbon-fiber frame, to achieve massive gains in fuel efficiency. In an industry that rewarded big, well-played bets, this was the right one. But the Dreamliner was hamstrung from the start by rigid demands on the use of capital from the CEO who replaced Condit in 2003 after a defense procurement scandal — Harry Stonecipher, the former McDonnell Douglas boss.

Stonecipher had an ever-combative answer for those who claimed he’d taken the cost focus too far. “When people say I changed the culture of Boeing, that was the intent, so that it’s run like a business rather than a great engineering firm,” he told The Chicago Tribune the next year. “It is a great engineering firm, but people invest in a company because they want to make money.”

As Boeing ramped up work on the Dreamliner in 2005, its R&D spending was only just more than half that of Airbus, according to estimates from Morgan Stanley. Stonecipher sold off giant parts-making operations, including a factory in Wichita that Boeing had owned for 75 years and employed 7,200 people. It might have improved the RONA numbers, but it made everyone’s jobs harder. Now when someone needed a part at the last minute or had an idea for a process improvement, it wasn’t a call with a colleague; it was a negotiation with lawyers, procurement-chain executives, human-resources representatives.

Alan Mulally, the longtime Boeing engineer who then ran its commercial airplanes business, remained upbeat in public, though some executives claimed they increasingly saw him escaping to a driving range at Jefferson Park in Seattle to smash buckets of golf balls. “In the old days,” he reportedly told a colleague in the parking lot one day, “you would go to the board and ask for X amount of money, and they’d counter with Y amount of money, and then you’d settle on a number, and that’s what you use to develop the plane. These days, you go to the board, and they say, ‘Here’s the budget for this airplane, and we’ll be taking this piece of it off the top, and you get what’s left; don’t (mess) up.’ “

One of the casualties of the efficiency drive was a building in Renton where Boeing had full-scale mock-ups to show off the interiors of its airplanes. Salespeople jokingly called it the Dirty Pool Room, because it was so supposedly unfair to Airbus. The walls had curved white lines marking, for instance, the less-roomy dimensions of an Airbus A340 cabin compared to a 777. While selling that plane back in the 1990s, Mulally had walked British Airways chairman Lord King through one of the mock-ups, fashioned from plywood, plastic and actual airline seats. He led the British lord by the shoulders, pushed him into seats and made a show of ducking under the A340’s lower overhead bins before standing up to full height. The salespeople loved having the room at their disposal any time they wanted.

In order to cut costs, Boeing had decided to sell the building housing the mock-ups. They went to Teague, a Seattle design firm that has advised on the interiors of Boeing commercial aircraft since the 1940s. The mock-ups were cut up and towed to a warehouse behind a furniture store on West Valley Highway, a sea of big-box retail. One Sunday, a group of Middle Eastern officials flew into Boeing Field to hear Boeing’s pitch for the new Dreamliner. U.S. marshals escorted the phalanx of limousines into the parking lot, where, outside the furniture store, a 30-foot inflatable gorilla with a top hat and a cigar was flapping away above their heads. A Boeing salesman asked one of the marshals to shoot it.

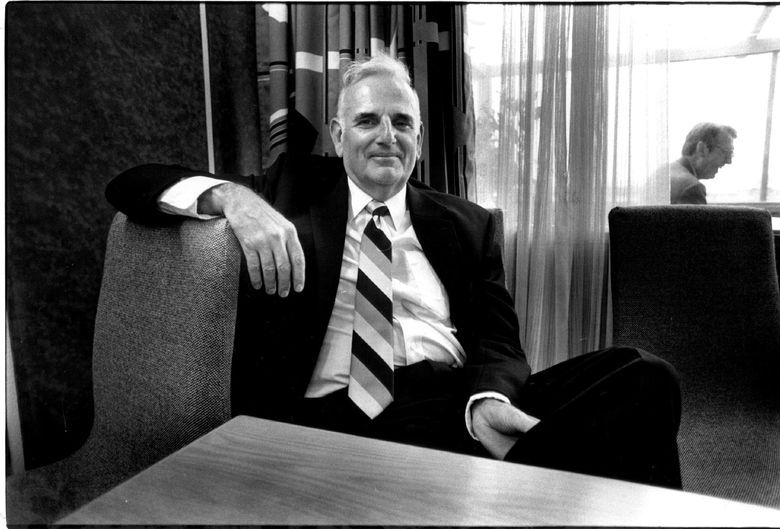

STONECIPHER’S RETURN was shorter than anyone expected. During a management retreat at a hotel in Palm Desert in January 2005, Debra Peabody, a 48-year-old executive in Boeing’s Washington lobbying office, came over and gave him an unusually long full-body hug as people gathered for an evening cocktail reception. The chemistry was so apparent that at least one of the executives there decided it was time to head back to his room, rather than witness the meeting between Stonecipher and Peabody. Someone passed intimate emails between the two to the board, and in March 2005, Stonecipher was fired. His wife of 50 years, Joan Stonecipher, hired the powerful Chicago attorney who’d represented rapper R. Kelly’s ex and filed for divorce within days. Stonecipher and Peabody eventually married.

Veteran Boeing people started dreaming of Mulally, one of their own, getting the top job. He’d always been the one they wanted. Back in the 1990s, the shuttle drivers who overheard everyone’s private conversations as they ferried people around Boeing’s giant campuses used to say it was only a matter of time before Mulally was running the place.

Mulally never openly campaigned for CEO; he was dismissive of what he saw as the more gauche efforts on behalf of the other main internal candidate, Jim Albaugh, the chief of the defense business. In the end, the board chose neither. It opted instead for one of its own, Jim McNerney, a Jack Welch protégé and Boeing board member who was then running the 3M Company.

McNerney had been a Boeing director since 2001, and, according to one person familiar with the deliberations, had also been the board’s first choice to replace Condit back in 2003. McNerney had rejected the overtures in part because his contract with 3M ran three years, and he would have lost lucrative stock payments if he’d accepted. This time the board gave him all the incentive he’d need to join Boeing — a pay package worth $52 million that replaced what he was losing at 3M. It was what’s known as a “golden hello,” and controversial because it guarantees pay before any performance.

“It wasn’t even a close call,” a former board member said of the decision. In selecting McNerney, the board had, once and for all, thrown in its lot with the financial engineers.

In truth, the board had duly considered the two Boeing insiders, but hiring McNerney would represent a coup for the scandal-tarred company. He had been one of the most highly regarded American business leaders ever since he’d been one of the three finalists in the much-publicized race to succeed Welch at GE. The influential recruiter, Gerry Roche at Heidrick & Struggles, told people he frequently got requests for a “McNerney type.” Within days of McNerney being named 3M chief, its stock had risen almost 20%. “The mere mention of his name made everyone richer,” as BusinessWeek put it.

Boeing veterans grumbled that the board must have thought Mulally, 5 feet 9 and still frequently described as boyish at age 60, just didn’t look the part of the stereotypical CEO. McNerney was 6 feet 2, Hollywood handsome, and had the de rigueur head of graying hair. It sounded like shallow gossip, but to the risk-averse Boeing board, appearances were indeed a factor — as was the perception that McNerney would pursue a more shareholder-friendly, predictable and less expensive strategy.

“There are just some people who look and act like a CEO,” the former board member said, drawing on tropes of the typical executive. “Some people say, ‘I know an NFL quarterback when I see them.’ Alan didn’t have that look and feel — he’s excitable, cheerleadery, high-energy, ‘We’re going to build that plane.’ “

Mulally, the Boeing lifer, was soon chafing under yet another new boss, having lost out once more on the top prize. Within a year, McNerney began pressing his team to rank-and-yank managers the way he had at GE. Mulally resisted, telling people at a meeting in 2006, “If you hire a team that you think is really good and they’re all performing well, why in the hell would you eliminate 10% every year?”

He wouldn’t have to dwell on that question for long. In September 2006, William Ford Jr. announced that Mulally would replace him at the helm of the Ford Motor Company, becoming the first nonfamily member to run the iconic automaker. Within a day, movers came to pack up his office and the conference room decorated with framed magazine articles and souvenirs. He said his goodbyes after 37 years from a bare room on a lower floor. Not long after, in a moment whose symbolism was all-too-painfully evident, the “Working Together” banner on the wall outside his office came down. For people who thought of Mulally as Boeing’s engineering soul, it was hard to watch. “The idealism just went out,” a Mulally lieutenant said. “It was no longer about working together; it was about something else — I guess shareholder value.”

The first inklings of trouble came that very year in a faraway corner of the baroque organization Boeing had assembled to build the Dreamliner, which one day, like the MAX, would be grounded for safety reasons by the Federal Aviation Administration. A 50-pound lithium-ion battery under development for the new jet caught fire at a supplier’s laboratory in Tucson, Arizona. The building was a total loss. It was a fiery symbol of a strategy that was also to go down in flames, if anyone thought to look.

About the book

“Flying Blind” draws from exclusive interviews with current and former employees of Boeing and the Federal Aviation Administration, industry executives and analysts, and family members of the victims of the 737 MAX. It tells the story of how Boeing went from being a treasured American innovator to ushering in one of the greatest corporate disasters of the 21st century. Copyright 2021 by Peter Robison. Published by Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.