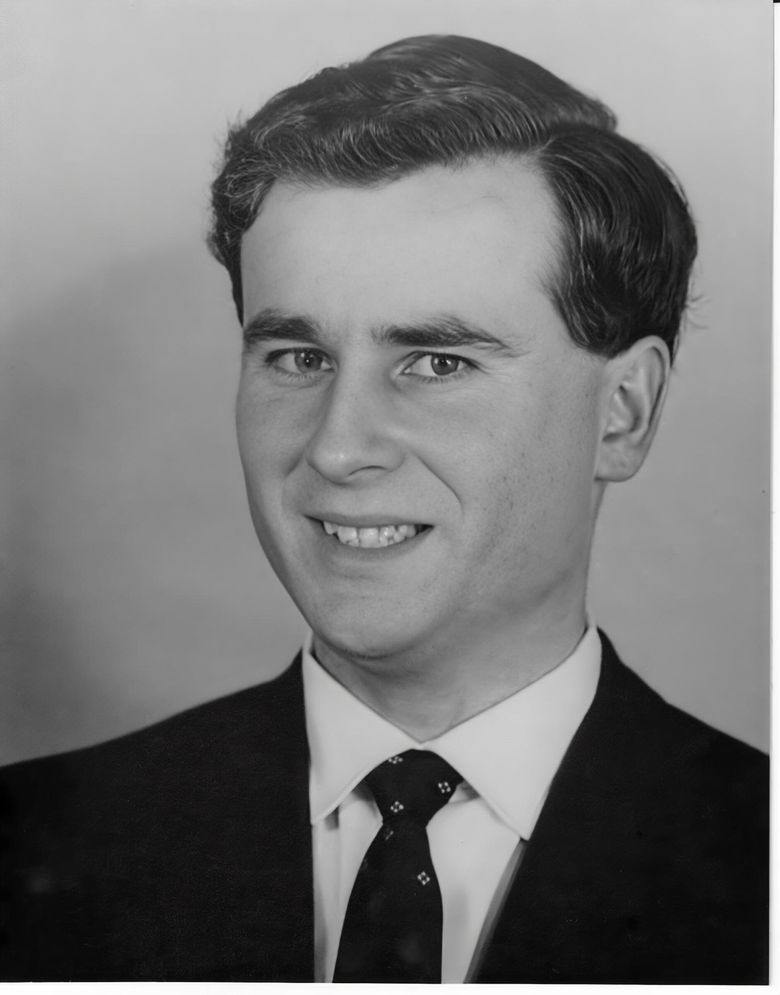

More than two decades ago, aerospace engineer John Hart-Smith, then already a world-renowned expert on designing aircraft structures, gained fame beyond his field when he warned Boeing management that its shortsighted financial focus would be ruinous.

In an internal Boeing presentation in 2001, and in essays written with hilariously dry wit and sharp insight, he lampooned America’s corporate business culture of outsourcing, cost-cutting and downsizing.

“I had lived through the destruction of Douglas Aircraft and I saw the same thing about to happen at Boeing,” Hart-Smith explained in a 2019 interview.

Boeing’s senior nontechnical leaders, champions of the management strategies he mocked, dismissed as naive the views of a top engineer about business matters. They sidelined him within the company.

Hart-Smith, revered for his technical know-how, admired for his force of intellect and loved by colleagues for his humble, endearingly eccentric personality, died in December, aged 84, at his home in Melbourne, Australia, long after Boeing’s trajectory had clearly proven his prescience.

His daughter Kate Hart-Smith said by phone he died of kidney failure on Dec. 13 after a couple of weeks in hospital. He was surrounded by family.

That day, he insisted on working from his hospital bed on a final engineering paper that he’s been developing for several years.

“He had his sons-in-law there helping him with the computer, just getting the last caption on the last graph. It was quite extraordinary. He was very determined to get that finished,” said Kate.

His family has submitted the paper to an engineering journal for publication.

Former Boeing Chief Technical Officer John Tracy announced Hart-Smith’s death on LinkedIn, a post that drew many comments from engineers, academics and aerospace figures all over the world praising his life and legacy.

In an interview, Tracy recalled first meeting the already-famed engineer in person in the early 1980s, seeking him out after reading his definitive early work on joining carbon composite aircraft parts.

“He was a superstar in the field. I was like a Little League guy, and I wanted to talk to Babe Ruth,” said Tracy, who would later be Hart-Smith’s boss at Boeing. “He was willing to talk to somebody that knew next to nothing, and help him. He was just the sweetest guy in the world.”

Yet Hart-Smith also quixotically and unflinchingly stood up against conventional wisdom if he considered it manifestly stupid.

Jim Ogonowski, former senior chief engineer for structures at Boeing Commercial Airplanes, said Hart-Smith “had absolutely no regard to hierarchy. It wouldn’t make any difference to him who he was speaking to, he would speak his mind.”

That 2001 internal paper “caused a lot of internal consternation among Boeing senior leadership,” Ogonowski said in an interview. “It took time, a lot of time, before eventually I would say he was proved correct.”

A passion took him far away

Leonard John Hart-Smith was born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1940.

His father, Leonard, grew up in a poor family during the Depression, won scholarships to university, earned a doctorate at Oxford, and later became director of National Parks in the Australian state of Victoria and an authority on lyrebirds.

Hart-Smith said he got his refined, almost British accent from his father.

Though his dad wanted him to be a doctor, the World War II boom in aviation ignited a different passion in a very young Hart-Smith.

“From 1942, planes were flying all over when I was growing up,” he said. “From the age of 2, I wanted to be an aircraft engineer.”

He earned a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering from Monash University and then landed a job in 1968 at Douglas Aircraft by writing to the chief engineer in Long Beach, Calif.

Married with two daughters, he began a four-decade career that meant spending much of the year in America.

He and his wife separated, but despite the time far away he maintained a close relationship with the children. Each Australian summer, he’d return and take his daughters along with his parents and siblings for a monthlong vacation at a national park.

His daughter Kate described her father as “very loving, very generous and really thoughtful.”

“He couldn’t have done his work the way he did if he’d stayed in Australia,” she continued. “We understand why he had to go.

“We loved him very dearly, and we knew that he loved us. The distance and the lack of direct contact really didn’t matter.”

An engineering icon

Hart-Smith’s work at Douglas, often under contract to NASA or the U.S. Air Force, won numerous accolades as he developed new methods to fasten or adhesively bond together both carbon composite and metallic structures, to analyze such designs and to test the results.

In one major Air Force research project, he developed a widebody fuselage that was adhesively bonded, without fasteners.

Ogonowski said Hart-Smith produced designs with an eye to making them easily manufactured so that his work “became almost gospel in the industry.”

He redesigned the composite tail cone of the giant C-17 military cargo plane, previously a single complex piece made from carbon composite prone to defects, breaking it into six easy-to-manufacture pieces bonded together that could be produced with zero defects.

“He was able to radically simplify the design and manufacturing,” said Tracy. “He had just a sixth sense understanding of what the load paths were.”

With that project alone, Hart-Smith saved the company many tens of millions of dollars, Tracy added.

In the late 1980s, Hart-Smith even helped fix a major structural problem for a Douglas competitor: Boeing.

Studying the contours around the cockpit on the 747 jumbo jet, he analyzed the loads and predicted cracks would develop in the fuselage frames. With the blessing of his bosses at Douglas, he shared this analysis with his peers at Boeing and when cracks were indeed discovered, his explanation of why it was happening allowed Boeing engineers to develop a fix.

“That gave me a lot of credibility within Boeing’s technical management,” Hart-Smith said.

Then, after Boeing’s 1997 merger with McDonnell Douglas, while Ogonowski and Tracy joined Boeing management as top technical executives, Hart-Smith was elevated to the top echelon of nonmanagerial engineers, becoming a senior technical fellow.

Standing up to Boeing’s leadership

Hart-Smith’s promotion brought with it a requirement to present a paper before the top engineering leadership at the next annual Boeing Technical Excellence Conference at the company’s Leadership Institute in St. Louis.

That’s where Hart-Smith had the chutzpah to present his detailed 2001 paper not on the technicalities of airplane structural joins but about Boeing’s business strategy.

He wasn’t as naive on this topic as top executives believed. He had a certificate in business management from UCLA, completing the course work for an MBA, though not bothering to do the internship required for the master’s degree.

Filtered through Hart-Smith’s independent intellect, those classes provided the fuel to fire his subsequent fierce mockery of business schools and of newly minted MBAs.

When the day of his technical fellowship presentation arrived, Hart-Smith was unable to travel from California as he’d just had surgery to insert a stent below his heart. So he delivered his talk by phone, with a colleague flipping the slides in St. Louis.

He presented essentially an economics paper, delivered with a trademark deadpan humor.

It scathingly critiqued the McDonnell Douglas strategy, now foisted on Boeing, of outsourcing work and divesting core design and manufacturing assets.

He explained in clear, commonsense terms how this would ultimately increase costs, lower profits and jeopardize Boeing’s ability to develop future airplanes.

Hart-Smith learned afterward from colleagues in the room that after he’d finished and hung up, Boeing’s then Chief Technical Officer Dave Swain stood up and spoke for a half-hour attempting to rebut Hart-Smith’s arguments.

“By the time he was through, there was no one in the room who didn’t agree with me,” Hart-Smith said dryly in 2019.

His paper buzzed from inbox to inbox within Boeing and was cited ever after by employees.

Winnie the Pooh takes on corporate America

With his fearlessly impish independence, Hart-Smith stood his ground in arguments and took no prisoners in technical debates.

Tracy recalls with laughter how Hart-Smith launched crusades to refute analyses of how composite structures fail published by other eminent engineers.

“He would write these technical papers where he would call these other scientists charlatans and snake oil salesmen,” Tracy said. “I had to keep everybody calm and nice. I said, ‘John, you can’t use the word charlatan in a technical journal article.’

“It’s not that he thought he was smarter or better than anybody. He was one of the most humble people that you could ever imagine,” Tracy added. “He was just so dedicated to his work and what he believed to be true.”

Ogonowski compared Hart-Smith to “almost like an Einstein type,” whose appearance and demeanor masked a fierce and brilliant intellect.

Indeed he had the personality quirks of a man whose brain focused intensely on his work and paid little attention to the mundane details of daily life.

His office was “an absolute disaster,” piled so high with stacks of papers and reference materials that the company fire department would urge Tracy “to get this guy to clean up his office; it’s a fire hazard.”

Hart-Smith procrastinated every year about filing his U.S. tax returns. He could barely handle the basic upkeep of his house in Long Beach. He worried over utility bills going unpaid while he was away in Australia.

His tastes were simple and frugal. His favored restaurant was Denny’s.

Endlessly pursuing his critique of management, in the 1990s Hart-Smith wrote a series of stories, circulated privately to friends and colleagues, that humorously depicted Winnie the Pooh besting teams of business consultants with common sense.

The “bear with very little brain” was a satirical stand-in for Hart-Smith, who in later years indeed shared Winnie the Pooh’s somewhat short, roly-poly stature.

Asked why he didn’t publish these well-written, funny pieces, he replied helplessly that Disney owned the copyright to Winnie the Pooh and “I don’t have contacts there.”

Given Hart-Smith’s antipathy to management, Tracy recognizes that when he rose to become the top manager of Boeing’s engineers, “I codified everything that he disliked.”

Nevertheless, Hart-Smith “still treated me like his friend.”

“It was hard not to love him, even when you were mad at him,” Tracy said, laughing again. “I loved that guy.”

Warning on the cost of the 787

In the mid-2000s, Hart-Smith fought another battle within Boeing, when he tried to warn that the plan to build the 787 Dreamliner was seriously flawed and would prove very costly.

He first joined other engineers in recommending that it be made from metal, not carbon composites.

In that period, Hart-Smith led a small research team that developed a new metal fuselage design that was cheaper to build and would last longer than previous metal fuselages. It was tested to five lifetimes without any fatigue cracks.

When Boeing insisted on building the 787 from composites, Hart-Smith advised against the concept of fabricating the jet from single-piece composite barrels, each made by a different major subcontractor.

He told them that perfectly joining these large fuselage sections would prove extremely costly. He wrote a report advocating a better approach: making the sections from curved, fuselage-length panels fastened together.

Management again refused to listen. And once again, time proved Hart-Smith right.

While the 787 is a hugely successful plane, in service at airlines around the world, it has been a financial disaster for Boeing with no hope of recouping the billions of dollars spent on its development.

Most recently, gaps at those fuselage joins stopped 787 deliveries for many months and have cost Boeing $6.3 billion to repair.

After Hart-Smith retired from Boeing in 2008, Ogonowski brought him back as a consultant until 2015.

“I respected his insight. It caused me to think, to make sure that I wasn’t drinking my own bath water,” Ogonowski said. “He would be the one to give a different perspective.”

Then, in full retirement, Hart-Smith focused for at least the past five years on that one final paper he wanted to write.

He believed he’d found an error in the standard academic theories about how thin shell structures like aircraft fuselages buckle under pressure, one that accounted for a significant discrepancy between theoretical projections and the actual test results airplane manufacturers work from.

The paper he finished in hospital on his dying day was his last shot at convincing academics to accept his position.

Ogonowski said it’s possible Hart-Smith may yet be proven right. “I hope so,” he said.

Hart-Smith is survived by two daughters, Kate and Sylvia Winfield, his brother Neil Hart-Smith and sister Helen Kosky, as well as four grandchildren and four great-grandchildren, all of Melbourne, Australia.

He has requested that his ashes be spread at Wilsons Promontory, the national park at the southern tip of mainland Australia where he spent those many summers with his family.