The near-catastrophic midair blowout of a door-sized fuselage panel on an Alaska Airlines 737 MAX 9 in January was caused by two distinct manufacturing errors by different crews on successive days last fall in Boeing’s assembly plant in Renton.

The first manufacturing lapse occurred within a four-hour window early Sept. 18. On the evening of the next day, in the space of about an hour, the second error was made by a different crew of mechanics, untrained to work on that fuselage panel, known as a door plug, according to federal investigative and internal Boeing records.

Boeing’s quality control system failed to catch the faulty work performed within those two windows.

The following detailed account of what happened as the MAX jet moved through the Renton factory — and of the characters now at the center of the investigation — is compiled from the transcripts of federal investigators’ interviews of a dozen Boeing workers, synchronized with an internal Boeing document obtained by The Seattle Times that tracked day-by-day the rework that led to the door plug lapses.

Transcripts show National Transportation Safety Board investigators homed in on specific times, and the specific workers involved, when the door plug work occurred. They even have details down to a conversation two workers had about a Gucci cologne sample.

Though Boeing says it has not identified the individuals directly responsible, it has placed two workers involved on administrative leave. A company investigator accused one of them of lying. That employee told the NTSB that Boeing has set the pair up as scapegoats.

The federal safety agency, whose investigation is ongoing and is not expected to be finished until next year, subsequently criticized Boeing’s sidelining of the two workers.

“You need to address good-faith mistakes with nonpunitive solutions,” NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy said in a public hearing this month, implying that assigning blame could discourage people from speaking freely.

Jon Holden, District 751 president of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers union, who represents the front-line assembly crews in Renton, said in an interview with The Times, “There’s no way one or two people are at fault.”

“This is bigger than that. This was a systemic issue,” said Holden. “And we want to solve it.”

This account by The Seattle Times takes the NTSB approach, offering no conclusion about individual fault. It lays out factually what is known and what remains a mystery, identifying by name those whom the NTSB named in publicly released documents and identifying others by their title or role.

The NTSB was unable to interview one critical participant: the manager of the door crew, who remains on medical leave since suffering a serious stroke last fall after the work was done, and several months before the Alaska flight blowout.

The fallout from the Jan. 5 blowout has left Boeing in crisis, facing an ongoing criminal probe, federal investigations and a limit on 737 MAX production until it can prove it has control of its manufacturing process.

The spark for the firestorm can be traced back to two days in September.

Rare work, few workers trained

The door plug that blew out on Alaska Flight 1282 at 16,000 feet over Portland had sealed a hole cut out of the fuselage for an optional emergency exit door installed by only a few airlines.

Most 737 MAX 9s, like the Alaska jet, have a plug there, not a real door. To a passenger seated at that location, it looks like just another cabin window.

And the mechanics in Renton assembling the airplane don’t typically have to do anything with a door plug. It comes fully installed from Spirit AeroSystems in Wichita, Kan., and there’s usually no reason to open it in Renton.

A specialized door crew in Renton of about 20 to 25 mechanics covering three assembly lines is dedicated to the work of rigging passenger, cargo and other doors. They work first shift, 5 a.m. to 1:30 p.m.

They are the only mechanics that do such work, and even they rarely deal with a door plug. A Boeing manufacturing record lists door plug work performed in Renton just four times last year, one time in 2022 and twice in 2021.

A 35-year veteran on the door team told NTSB investigators that he is “the only one that can work on all the doors” and he was typically the only mechanic who would work on door plugs.

That mechanic was on vacation on the two critical days, Sept. 18 and 19 last year, when the door plug on the Alaska MAX 9 had to be opened and closed.

Sept. 1: Door plug in the way

The fuselage for the plane that would become Alaska Flight 1282 arrived by train in Renton from Wichita on Aug. 31. The next day, Boeing records show, it was inspected, and a small defect was discovered: Five rivets installed by Spirit on the door frame next to the door plug were damaged.

That day, the Friday before the Labor Day weekend, repair of those rivets was handed to Spirit, which has contract mechanics on-site in Renton to do any rework on its fuselage.

In the meantime, inspectors gave mechanics the OK to install insulation blankets, which covered the door plug.

By the following Thursday, a Spirit mechanic had logged an entry in the official Federal Aviation Administration-required record of this aircraft’s assembly — the Common Manufacturing Execution System or CMES, pronounced “sea-mass” by the mechanics — that the rivet repair was complete: “removed and replaced rivets.”

But that day, a Boeing inspector responded with a scathing rebuttal, stating that the rivets had not been replaced but just painted over. “Not acceptable,” read the work order.

On Sept. 10, records show Spirit was ordered a second time to remove and replace the rivets.

In Renton, Boeing uses a messaging system — the Shipside Action Tracker or SAT — for managers to track progress on fixing problems that are holding up production. The NTSB released a heavily redacted copy of the SAT record for future Alaska Flight 1282. The Seattle Times obtained an unredacted copy.

SAT entries show that after several days, the still-unfinished work order was elevated to higher-level Boeing managers.

On Sept. 15, Boeing cabin interiors manager Phally Meas, who needed the work finished so he could get his crew to install cabin walls and seats, texted on-site Spirit manager Tran Nguyen to ask why the rivet work hadn’t been done, NTSB interview transcripts show.

Spirit mechanics couldn’t get to the rivets unless the plug door was opened, Nguyen responded. He sent Meas a photo from his phone showing it was closed, according to the transcripts.

It wasn’t Spirit’s job to open the sealed door plug. Boeing’s door team would have to do that, the records show.

“He kept asking me how come there wasn’t work yet,” Nguyen told the NTSB. “The door was not open. That’s why there wasn’t work yet.”

By Sept. 17, the door was still closed, the rivets still unrepaired. The job was elevated again, to the next level of managers.

On that day, according to the SAT record, senior managers worked with Ken McElhaney, the door crew manager in Renton, “to determine if the door can just merely be opened or if it needs removal.”

They concluded that a CMES entry would be required if the door plug was totally removed, according to the SAT entry.

But this suggests a misunderstanding that could prove critical.

In fact, even just opening the door plug, swinging it outward on a hinge at the bottom, should have been recorded in CMES because it entails removing four critical retaining bolts. A quality alert Boeing issued exactly eight weeks earlier told employees even a partial removal needed to be documented.

But no removal was recorded.

At the NTSB hearing this month, Machinists union representative Lloyd Catlin testified that there should have been two removals documented in CMES: one for removing the insulation blanket at the door plug and a second for opening the plug.

He said both would have triggered an extensive reinspection before closing the door and putting the insulation blanket back.

Boeing’s repeated changes to instructions about when inspections were needed have sown confusion, and the company’s training on those changes has been inadequate, Catlin said. He noted that a 2022 FAA investigation faulted the company for both of those issues, and Boeing’s workforce has become less experienced since the pandemic.

The day after the discussion about whether a removal needed to be documented, the first key error was made.

Sept. 18: The first critical manufacturing lapse

There had been as many as 15 different door crew managers in Renton over three years, the veteran mechanic told the NTSB. He said McElhaney had come in from a different Boeing work area only about five or six months before the Alaska jet was built in September 2023.

Most members of McElhaney’s crew work in the first three days of an aircraft’s assembly when the bare fuselage, still without wings, is cradled in a large holding fixture while wiring, systems and insulation blankets are installed.

But by Sept. 18, mechanics had added the wings, landing gear and engines to the Alaska plane as it moved along the assembly line, and it had reached the last station before a completed jet rolls outside.

A small subcrew of four door crew mechanics and two team leads — called door masters — was assigned to work the “final fit, form and function” before rollout, essentially any work left over to finalize the doors.

By that morning, the rivet repair job was now urgent. Final installation of insulation, walls and seats around the door plug were still pending, according to the transcripts.

Everyone who comes near the plane must badge in when they arrive and leave, creating a record of who was present at any moment.

Michelle Delgado, an experienced contract mechanic for Spirit, told the NTSB she stopped by the plane shortly after her shift began at 6 a.m. and checked to see if the door plug was open so she could fix the rivets. It wasn’t.

At 6:48 a.m., a Boeing mechanic identified as a Door Master Lead texted a young Trainee mechanic on his team to come to the Alaska jet and open the door. The NTSB interviewed but did not name the Trainee or the Door Master Lead, who had almost 16 years at Boeing.

Filling in for the veteran mechanic on vacation, the Trainee was perhaps the least equipped to do this atypical job. He’d been at Boeing for about 17 months, his only previous jobs being at KFC and Taco Bell. “He’s just a young kid,” the Door Master Lead said.

At 7:17 a.m., an SAT entry stated: “Door is being opened per Ken McElhaney (Door Crew Manager).” The job of fixing the rivets, now underway, was downgraded back to lower-level managers.

Here the story told by the Door Master Lead and the relatively new Trainee mechanic takes an abrupt turn.

The pair told the NTSB that at 6:49 a.m., a minute after the initial text, the Door Master Lead called the Trainee and told him he’d just realized that this was a MAX 9, and so what needed to be opened was likely a plug, not an actual exit door.

The Trainee said the Door Master Lead told him to check on the computer whether the plane was a MAX 9, and if it was, “don’t even bother heading down there and go back to what I was doing.”

In his NTSB interview, the Door Master Lead told investigators he didn’t want his team dealing with plug doors.

“A plug door doesn’t have a handle, so it’s got things, weird bolts that go through,” he said.

“Plug door takes special tools which I do not know what the guys use to take it off,” he said. “I don’t mess with them.”

Between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m., two other mechanics on the door crew, identified in the NTSB documents as the Temporary Team Lead and a Door Installer, badged in together on the Alaska jet. Both had joined Boeing a few months after the young Trainee, yet had prior experience as machinists.

McElhaney, their manager, came aboard the plane for about 20 minutes in that hour, but the two mechanics don’t recall speaking with him.

Shortly after 8 a.m., the young Trainee connected again with the Door Master Lead, who texted him to come to his desk by the Alaska airplane.

But this wasn’t about the door plug, the two said. When the Trainee arrived at 8:37 a.m., the Lead said, he handed him a Gucci fragrance sample.

“It’s very expensive, Gucci cologne. He’s been trying to find it,” the Door Master Lead recalled. “He was ecstatic.”

Around 9 a.m., the Trainee shadowed the Temporary Lead, training on over-wing exit doors and the forward cargo door.

At 10:05 a.m., a Spirit manager said “access is now available and a Spirit mechanic will be assigned to begin work today,” according to an SAT entry. The same entry is repeated at 11 a.m.

These entries narrow the window when the plug was opened to between 7 a.m. and 11 a.m.

All four of the door crew mechanics who were present on the plane at various times that morning — the Door Master Lead, the Trainee, the Temporary Team Lead and the Door Installer — told the NTSB they did not see who opened the plug door.

McElhaney, their manager, suffered a severe stroke later that fall and has been out on medical leave since, unavailable to the NTSB investigators.

Reached by phone, he said he has lost half his sight and is numb on one side. He has no memory of any details, or even the names of those who worked under him.

Whoever did the work should have recorded it, he said. “To rework, there has to be paperwork.”

Yet because no record of the opening of the door plug is entered into CMES, there was no reinspection upon closing.

“You lied”

In the aftermath of the Jan. 5 door blowout, Boeing took the company-issued cellphones of the Door Master Lead and Trainee, which contained the thread asking the Trainee to go open the door plug.

In separate NTSB interviews, the pair gave parallel accounts of what was said in the subsequent voice call canceling that order, and of how their interaction at 8:37 a.m. was about the cologne, not the door plug.

But the Door Master Lead said a Boeing investigator railroaded him and accused him of lying about the door plug. “He was like, ‘Oh, well, you lied.’”

“I got accused of doing it, even though my name is nowhere on this SAT,” he said.

In late February, Boeing reassigned the Door Master Lead and the Trainee to a facility inside the 737 wing fabrication building, away from the final assembly lines, where they said they had little work to do.

At the NTSB hearing in Washington, D.C., this month, Boeing Senior Vice President of Quality Elizabeth Lund explained that this is standard practice “when a question arises about an employee’s involvement in a safety-related issue.”

“We will move them to a lateral position. Same pay, same benefits, same shift, off the airplane, while we finish our investigation,” she said.

That’s not how the two employees saw it.

“They moved me, out of sight, out of mind,” the Door Master Lead told the NTSB. “They put me in 420 [wing fabrication] building and way back in the back, literally in a jail, in a cage.”

Boeing subsequently put both employees on paid administrative leave.

Rivet repair begun

At 2:30 p.m. Sept. 18, the Boeing door crew had left. An SAT entry cites Spirit manager Nguyen saying the rivet job “is currently being worked.”

Delgado removed the rivets, cleaned the holes and ordered new rivets to be sent.

She snapped a photo of her arm holding aside the rubber seal around the plug and texted it to Nguyen to show she was able to make the fix without removing the seal. “I knew how to finesse it,” she said.

A Spirit inspector checked and signed off on her work in CMES. Delgado left the airplane at 3:36 p.m.

At about 5 p.m., a Boeing team arrived, their job being to close up the plane for weather protection so it could move outside that night. The team, called a Move Crew, found the door plug open and lying horizontally on a stand.

“I just grabbed the door and pulled it up. Pretty loose,” the Move Crew Team Lead told the NTSB; he was not identified. “It didn’t seem to fit well. Nothing to hold it.” Somebody found a strap to hold it closed. His team finished their work and left.

The next day, the door plug would be swung open again for the rivet replacement.

Sept. 19: The second critical lapse

The next morning, the plane hadn’t been moved outside, increasing the pressure to get it finished. The SAT states the replacement rivets arrived from Everett shortly after noon.

Assisted by another mechanic, Delgado returned to install the new rivets around 2 p.m. and left at 3:11 p.m. A Spirit quality inspector signed off on it at 6:11 p.m.

Between 4:15 and 4:45 p.m., an SAT “Team Captain,” who acts as a liaison between mechanics and managers to deal with production issues entered in the system, was asked to get the door closed.

Going to the plane, the Team Captain saw the door plug swung open, lying flat on a stand. The insulation and cabin walls weren’t installed yet. He sent photos to Meas, the Boeing interiors manager.

At about 5 p.m., Meas told the Team Captain’s crew that it needed to be closed. Within an hour, it was, he later told the NTSB. He said he may have heard that from one of his mechanics, but he didn’t see who closed it.

The Team Captain recalled hearing someone on the periphery, probably one of the mechanics badging out, say, “We’ve got it figured out,” then glancing up from the floor beside the airplane and seeing the door plug was closed.

At 5:33 p.m., Boeing interiors manager Bounthavy “Davy” Phakoxay texted Meas saying, “All done.”

At 6:39 p.m., Meas texted Phakoxay that one piece still needed to be done before his team could install cabin walls and seats. He sent a photo of the door plug closed but with insulation hanging from above.

“I need to be done tonight,” Meas texted.

Phakoxay did not go to the airplane but sent a mechanic to fix the insulation. He told the NTSB that this mechanic “verified that it was completed, but there is no paperwork.”

This timeline suggests the door plug was closed at about 5:30 p.m., certainly by 6:39 p.m. No entry was logged in CMES.

It probably would have taken a couple of people to “figure out” how to close the plug.

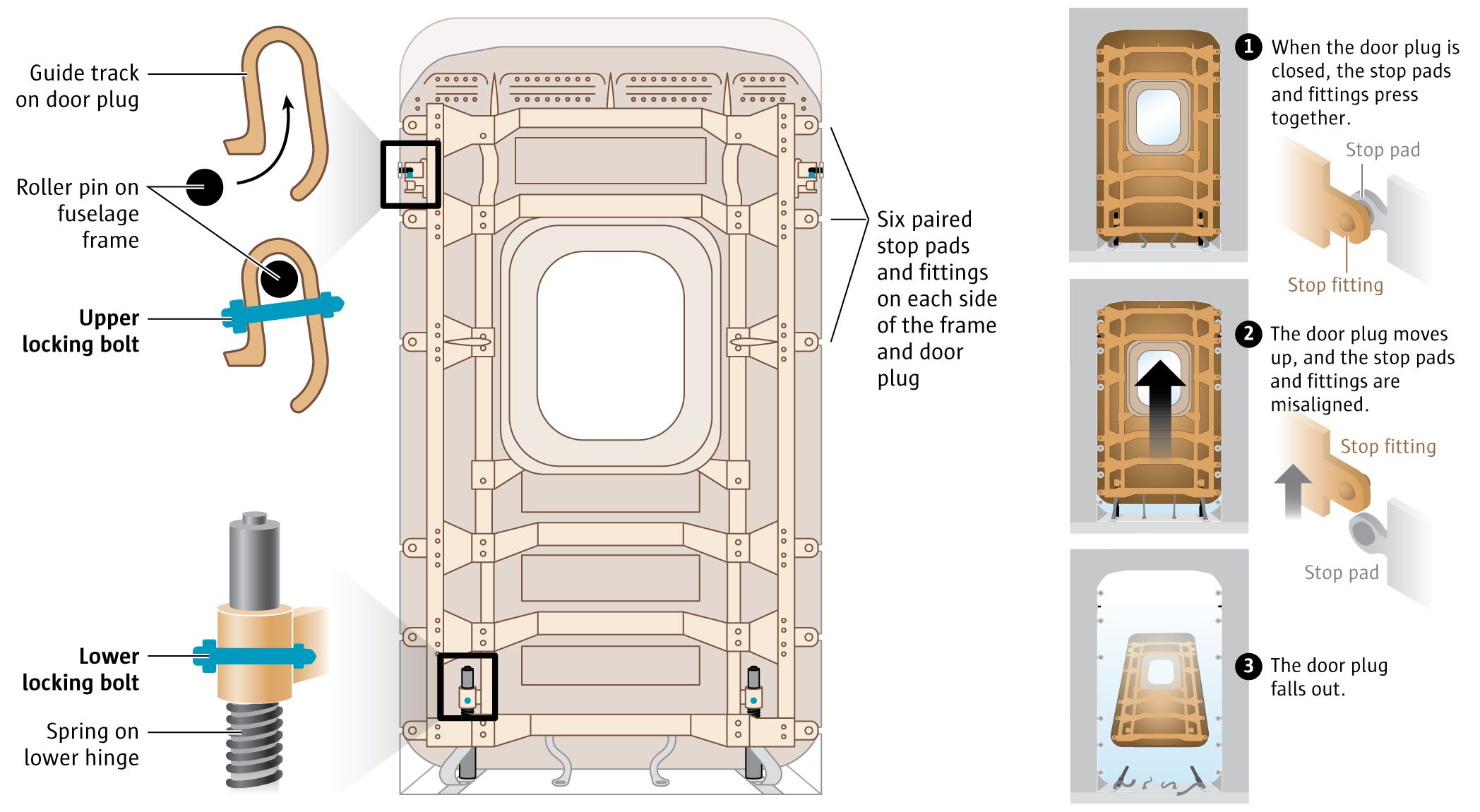

They would have had to pull it up off the stand and guide metal pins on either side of the door frame into slots on the plug. Six small fittings on each side of the plug would then have aligned with corresponding pads on the door frame, making the plug appear snugly closed.

It’s unknown who did this. None of the door crew was scheduled to be working then. The mechanics installing interiors were not qualified to work on doors, much less door plugs.

No quality inspection of the door plug was conducted, since no record of its opening and closing was ever entered in the system, documents show.

The NTSB interviewed three mechanics who installed passenger seats and were on the aircraft at that time. All were young and with little experience. None remembered seeing an open door plug.

Meas, the interiors manager, wouldn’t have noticed when he took his photo at 6:39 p.m., but with hindsight and the eye of a door crew, the image incidentally reveals that at least three of the four critical retainer bolts are missing; one bolt position is not visible.

The veteran Boeing door installer, the one out on vacation that day, later told the NTSB that “the person that closed the door didn’t know what they were doing.”

In a statement, Spirit declined to comment “as this matter remains under investigation.”

Boeing deferred comment to the NTSB and did not make Meas and Phakoxay available for interviews. The Times contacted Meas, who said he was too busy to talk. Messages left at a phone number for Phakoxay were not returned.

The NTSB does not assign blame to any of the workers it mentioned by name in the interview transcripts. Its investigation is continuing and additional interviews will be conducted. Its final report could take as long as a year.

The FBI is also investigating for potential criminal negligence and has issued subpoenas using a Seattle grand jury. That investigation is ongoing, according to a person familiar with the case.

Blowout

The MAX 9 rolled out of Boeing’s Renton factory Sept. 20. After it was painted in Alaska’s colors and fuel tests were conducted, it took its first flight Oct. 15 and was delivered to the airline Oct. 31.

Without the retaining bolts to hold the metal pins in the slots on the door plug, vibrations from takeoffs and landings over 154 flights of the airplane must have allowed the plug to move gradually upward.

On Jan. 5, soon after takeoff from Portland, the plug moved above the pads holding it in place and blew out.

In the seats just ahead of the plug, a mother clutched her teenage son, whose clothes had been ripped off his upper body, and held on tight as she stared into the darkness of the gaping hole.

Seattle Times staff reporter Lauren Rosenblatt and researcher Miyoko Wolf contributed to this story.