Editor’s note: This story references suicide. If you or a loved one is in crisis, resources are available here.

During his 12 years as a quality inspector at Spirit AeroSystems, Santiago Paredes prided himself on speaking his mind when he found errors.

Mistakes have been pervasive at the Wichita, Kan., Spirit plant that employed Paredes, where the company builds large sections of Boeing planes, including the entire fuselage of the 737 MAX.

Paredes’ bosses appreciated his attention to detail — to a point. But when he relentlessly pointed out manufacturing flaws, Paredes says, supervisors labeled him “a showstopper,” ignored his findings and pushed along flawed fuselages to Renton.

Paredes, worried a plane would crash due to known defects, quit and moved his family of five out of Wichita to “restart my life without Spirit in it,” the 41-year-old said. But his concerns followed him.

Inspired by a Spirit colleague turned whistleblower, he told federal investigators that unbeknown to Boeing, Spirit was storing incomplete, flawed MAX bodies during the COVID-19 pandemic, when shipments to Boeing’s Renton factory were paused.

Paredes lacked faith in the Federal Aviation Administration — long accused by critics of too-tight ties to industry — and its whistleblower system. So Paredes sidestepped the FAA’s in-house whistleblower process, instead taking his concerns directly to federal investigators as a witness in a stockholder lawsuit against Spirit.

Meant to enable whistleblowers to freely report anomalies that affect the safety of air travel, the FAA’s system and those run in-house by major aerospace manufacturers draw focus after air disasters or accidents like one over Portland in January. The disclosures are meant to provide FAA safety officials windows into problems that could render planes unsafe to fly, and to ensure the flying public never boards one.

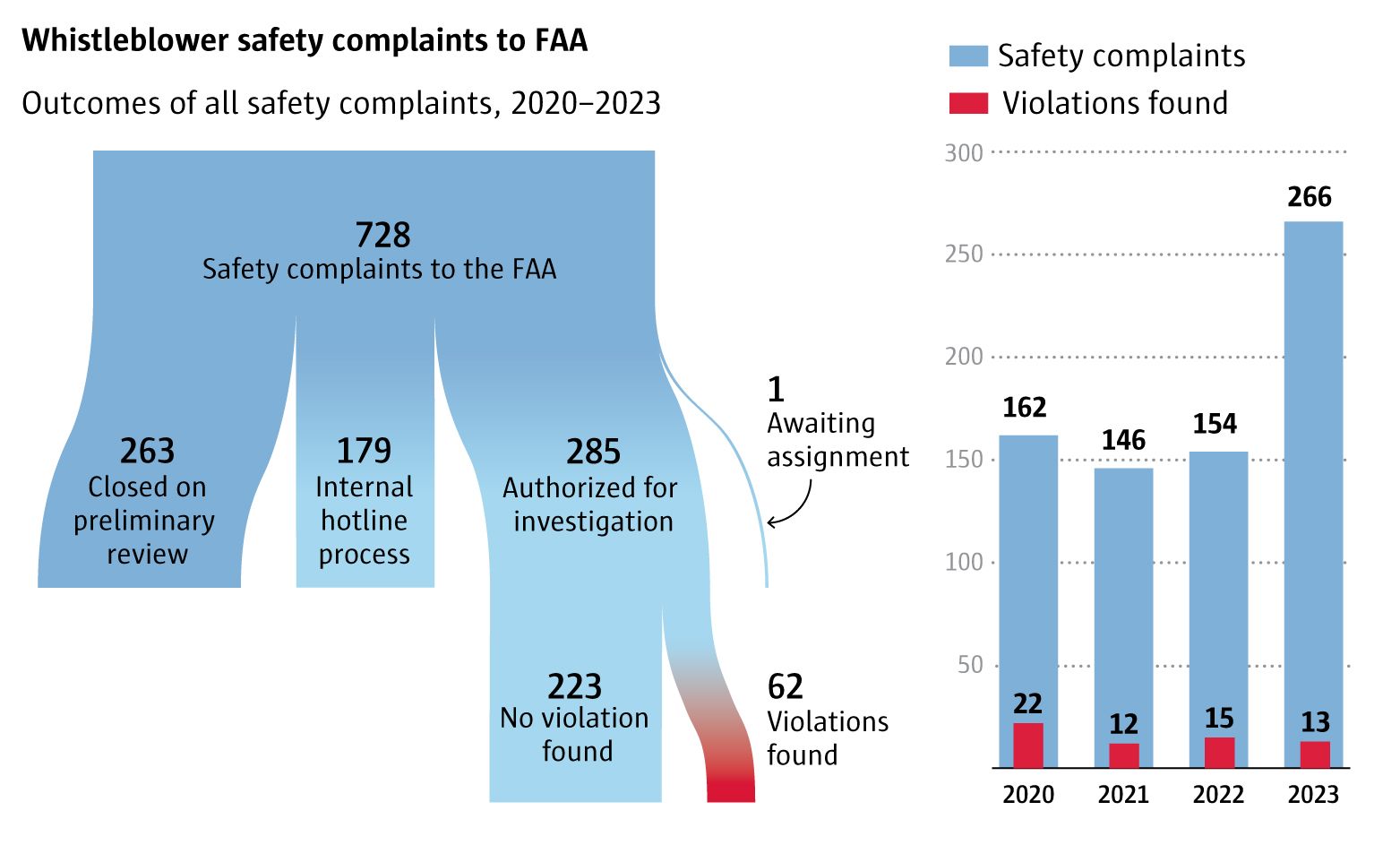

A Seattle Times analysis of that FAA program’s reports to Congress shows an overwhelmed system delivering underwhelming results for whistleblowers.

Aerospace and airline workers and FAA employees who share safety concerns face a system where the probability of success is only slightly better than the chance of drawing an ace from a 52-card deck. More than 90% of safety complaints from 2020 through 2023 ended with no violation found by the FAA, while whistleblowers reported them at great personal and professional risk.

The FAA dismisses whistleblower complaints on preliminary review when they lack sufficient information to investigate, repeat an allegation that’s already being investigated or lack a basis for retaliation claims. It’s impossible to know how many of the hundreds of complaints the FAA summarily dismisses each year are in fact meritless. In interviews, though, whistleblowers and their advocates said even those whose claims ultimately prove out succeed at incredible costs.

Concrete changes to the whistleblower system put forward by reform advocates — legal representation at public expense, creating a more independent alternative to the FAA’s in-house system — would bolster enhancements made to the FAA program four years ago in the wake of two MAX crashes but have yet to gain traction in Congress.

While Spirit declined to comment about Paredes’ whistleblower complaint, Spirit, Boeing and the FAA all said that they are committed to protecting whistleblowers and striving for improvement.

“Voluntary reporting without fear of reprisal is a critical component of aviation safety, and FAA Administrator Mike Whitaker has made employee safety reporting a priority,” FAA spokesperson Ian Gregor said. He noted the FAA and Congress created the agency’s current system in response to failures in the one that preceded it.

Of the 728 complaints related to the safety of aircraft the FAA has received since 2020, the Office of Audit and Evaluation dismissed nearly 4 out of 10 before reaching the fact-finding phase, according to congressional reports. It relies on investigations by the Office of Audit and Evaluation and input from groups of FAA subject-matter experts. Overall, 8.5% of safety complaints resulted in findings of violations.

The FAA discards complaints that it judges lack sufficient information, or fail to rise to the threshold of a whistleblower claim because the FAA doesn’t believe a complaint threatened the whistleblower’s employment, according to Gregor.

Since 2020, the FAA found violations and took action on complaints related to inspections at Boeing plants. At the same time, it closed investigations into issues similar to those believed to have contributed to a blowout over Portland in January, such as unqualified workers performing safety-critical work and missing documentation. That incident, which saw an improperly installed door-sized panel fall off a 737 MAX as the plane climbed to 16,000 feet, triggered familiar questions from Congress and the flying public about the commitment to safety at Boeing, Spirit and the FAA.

For whistleblowers whose cases advance, a stormy and emotionally taxing process awaits. Whistleblowers, their advocates and the people closest to them describe a dizzying odyssey that favors the accused and gnaws away at the whistleblowers.

Paredes contends his objections saw him indelibly labeled as a problem employee. In May, more than a year after he’d left Wichita, the quality director at Paredes’ new employer got a phone call from someone at Spirit.

“They told him … they have a mole,” Paredes said.

“They were trying to impact my employment, my income. As a middle-class man, it’s not easy to provide for my family,” he said. “It made it hard to go to work, the rumors on the floor.”

Spirit, through its spokesperson, declined to answer questions about Paredes’ retaliation claim.

Like Paredes says happened to him, whistleblowers’ identities sometimes are leaked to the people they’re complaining about, leading them to be retaliated against by managers and shunned by peers. Those who quit or get fired face prolonged unemployment, financial insecurity, divorce, depression. Some die waiting for their complaints to be resolved.

“It’s a David versus Goliath power imbalance,” said Jackie Garrick, president and CEO of Whistleblowers of America, a nonprofit aimed at supporting whistleblower mental health. “David had God on his side. Most whistleblowers are pretty much alone …

“They are that small guy going up against the big guy with no real weapons but the truth, and the truth gets treated like it’s a crime.”

Betting on “independence”

After a misdesigned system downed two 737 MAX airliners six years ago, whistleblowers illuminated Boeing’s resistance to worker complaints and the FAA’s weak regulation of the company, and forced Congress to act. But based on the accounts of whistleblowers and their advocates, policy tweaks have done little to protect whistleblowers from the punishing process and culture of exclusion.

On its website and in official reports to Congress, the FAA describes its in-house whistleblower and appeals processes as “independent.” But that’s a misnomer, according to whistleblower advocates familiar with the system.

Unlike most federal agencies, the program relies on the FAA’s administrator as the final authority on its investigations, according to Tom Devine, a whistleblower attorney with nearly a half-century of experience across a spectrum of federal agencies, particularly those with security clearances to conduct secretive work. Devine is also legal director of the Government Accountability Project, a nonprofit that helps whistleblowers navigate the complex federal system.

Whistleblower advocates view the system as an extension of “regulatory capture,” when oversight agencies fall under the influence of the industries they’re supposed to be policing, something Congress acknowledges Boeing has exercised over the FAA. One recent FAA chief, ex-Delta Air Lines executive Stephen Dickson, was appointed to the top job despite allegations that he and others at Delta retaliated against an airline whistleblower who reported safety concerns.

Rulings within the FAA’s whistleblower protection program pass through the FAA’s legal office. In truly independent systems, usually operated by an agency’s inspector general, Devine said, agency attorneys and politically appointed leaders are cut out of the entire process.

FAA spokesperson Gregor cited a legal prohibition against the agency’s administrator blocking the investigation of complaints. Gregor said whistleblower protection at the FAA has only gotten more independent since moving the program out of the agency’s chief counsel’s office in 2012, and with the recent adoption of the same professional standards required of federal inspectors general.

In response to a congressional directive, the FAA in 2022 stood up its Office of the Whistleblower Ombudsman to educate FAA employee-whistleblowers about their rights.

In 2022 and 2023, 20 FAA whistleblowers turned to the new office with their complaints. Of those, 16 involved allegations of retaliation. Three were dispatched by simply advising employees of their rights and remedies should they face future retaliation.

One advocate compared the FAA’s whistleblower protection program to a casino — a stacked system that favors the house. It invites all comers, offers slim chances of success and often spits them out in worse shape than when they walked through the door.

Aerospace pros have several paths within the federal government to lodge whistleblower complaints. Each path is littered with procedural requirements; one misstep can doom a complaint.

Aside from the FAA’s in-house program, employees of Boeing, Spirit and the FAA can report safety hazards to the Office of Special Counsel, which has no FAA ties, or through internal employer complaint programs, such as Boeing’s Speak Up and Spirit’s Quality 360, to trigger company reviews. Allegations of retaliation against aviation whistleblowers are investigated by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Depending on which route a whistleblower chooses, deadlines for next steps can range from five to 90 days. Some require complaints be presented on a specific form, or they are discarded.

In the aftermath of the door-plug blowout over Portland, Boeing specifically asked its employees to use the Speak Up program or the FAA’s internal process to report any concerns, according to Boeing spokesperson Jessica Kowal.

Both have done a poor job protecting whistleblowers from retaliation, according to a congressionally appointed expert panel.

In hearings before Congress following the MAX crashes and the more recent blowout, experts criticized both Boeing’s Speak Up program and the FAA’s whistleblower protection system. While both were designed to guard against retaliation, critics say they have instead become enablers of it.

“We’ve warned whistleblowers not to entrust their rights there,” Devine said, referring to the FAA’s in-house whistleblower program. “It’s been a disaster from the beginning. We tell everyone to avoid it because it’s a trap.”

A panel of aviation safety experts in February rebuked Boeing’s Speak Up program in a report to Congress. Whistleblower advocates criticized Speak Up for commonly outing whistleblowers to the supervisors they’re complaining about, exposing them to retaliation. Managers sometimes investigated complaints against themselves. Employees mistrusted the program’s promise of anonymity.

Collectively, the befuddling maze of whistleblower options sowed “confusion about reporting systems that may discourage employees from submitting safety concerns,” according to the expert panel’s report.

FAA employees can appeal demotions to the agency-run Guaranteed Fair Treatment Program. Whistleblowers and their advocates who’ve tested the process say it’s anything but fair, as former FAA employee Jason Brock would learn the hard way.

Endurance tested by bureaucratic process

Brock spent 14 years working for the FAA at a Nashville, Tenn., airport. He filed a complaint accusing his supervisor of telling him to install runway lights, something Brock said he wasn’t qualified to do safely. Brock was terminated in 2020 for refusing to do the work, and his initial complaint was rejected by the FAA’s Office of Audit and Evaluation.

That office fields complaints on the agency hotline, acting as a gatekeeper. Hotline complaints pass through a process that can dismiss them or route them to internal investigations. Sometimes, the FAA assigns whistleblower complaints to this track, as it did with Brock’s.

When he appealed his firing to the Guaranteed Fair Treatment Program last year, Brock said he was informed that the program didn’t have enough arbitrators to hear his case, so Brock filed a federal lawsuit challenging the FAA’s rulings.

Brock, who’s acting as his own lawyer, points to emails from an FAA employee in May 2020, stating that it lacked arbitrators to hear his case. Brock said the FAA’s denial demonstrates its reluctance to acknowledge, much less fix, its shortcomings.

“Guaranteed Fair Treatment Program? Yeah, right,” Brock said with a sarcastic chuckle. “It hurts my heart to know that there are other cases like mine.”

The FAA, through its spokesperson, denied it has ever lacked arbitrators in the program.

As Paredes had from the start, Brock abandoned the FAA’s process entirely. He instead appealed to the Merit Systems Protection Board, an option available to federal employees, as well as people who work for government contractors or regulated companies, who’ve been demoted, reprimanded or dismissed. The board overturned the FAA’s decision, enabling Brock to continue to fight in federal court.

While the FAA’s program may be unusual in its lack of independence, similar complaints are often made against other federal agencies’ whistleblower systems. Devine said even more-independent reporting paths seldom yield satisfying outcomes. It’s standard for large percentages of whistleblower complaints to be dispatched before a full fact-finding review, regardless of the venue.

Aerospace whistleblowers must finance their cases, sometimes balancing payments to lawyers with essential household bills when they’ve been fired. They can’t subpoena witnesses, unless their complaint progresses to a lawsuit. Whistleblowers very rarely win their cases on initial review because federal whistleblower programs base preliminary findings primarily on the word of the accuser against the word of the accused. Generally, the accused is a corporation or federal agency with lawyers, lobbyists and mastery of the bureaucratic process.

In June, Boeing quality inspector Sam Mohawk made public his allegations that the 737 MAX line in Renton was losing track of subpar aircraft parts. Mohawk worried the missing parts had found their way into planes. He also alleged Boeing hid flawed parts from the FAA.

Boeing conducted two investigations into Mohawk’s claims. The company reviewed documents, observed the factory operations and interviewed other employees. Boeing found no evidence defective parts were installed on aircraft and determined none of the concerns Mohawk raised affected airplane safety, Kowal said.

Even so, Boeing said Mohawk’s disclosure was useful. Kowal said it showed the importance of sharing information with employees.

That’s not unusual. Claims by public whistleblowers in the past year have led to some improvements at Boeing’s factories, while others “were not accurate,” according to the company. In the final analysis, the company’s position is that no whistleblower complaints affected safety for the flying public.

“Based on investigations over several years, none of their claims about airplane safety were found to be valid,” Kowal said. She said the company encourages employees to report any safety concern. “We carefully investigate every concern and take action to address any validated issue.”

Mohawk continues to pursue his FAA claim, originally submitted through Boeing’s Speak Up program.

Months passed before Boeing addressed Mohawk’s complaint. When it did, Mohawk’s report was passed to the managers he was complaining about, according to Brian Knowles, Mohawk’s South Carolina-based lawyer.

“If you do Speak Up, just know that your report is going to go straight to the guys you’re accusing of wrongdoing. They aren’t going to say, ‘Thanks for speaking up against us,’” Knowles said.

According to Knowles, Boeing CEO Dave Calhoun promised to meet with Mohawk over the summer, shortly before Calhoun stepped down in August. But the tentative meeting never materialized; Boeing said the timing of Calhoun’s resignation scuttled the meeting. Mohawk is still waiting.

Mohawk’s unsatisfying whistleblower experience within the FAA system mirrors Brock’s, except Brock says his complaint has rendered his life unrecognizable.

He faced prolonged unemployment after the FAA fired him, before landing at Boeing’s St. Louis plant, a 4 ½-hour drive from his wife and children, who Brock was only able to travel home and see on weekends. That’s changed; Brock got notice in November that he was laid off.

“It just got to be too much”

Among many aerospace whistleblowers who’ve come forward in the years since Boeing and the FAA promised to improve their support for whistleblowers, two names stand out, forever linked by conscience and coincidence: John Barnett and Josh Dean.

Both died this year, 52 days apart and months after the blowout over Portland reignited old questions about the commitments to quality and safety at Boeing and Spirit.

The whistleblowers’ deaths became an overnight fixation, spawning conspiracy theories. They also focused the public eye on the stress and sacrifices made by workers who raise concerns directly related to air safety. According to people close to them, Barnett and Dean endured deep emotional trauma from their whistleblower experiences, pain that became increasingly apparent as they neared the end of their lives.

Barnett, 62, died by suicide in South Carolina in March. For seven years, he had claimed Boeing retaliated against him for complaints about quality lapses.

He worked at Boeing for 32 years before resigning with work-related post-traumatic stress disorder in 2017, the same year he filed the whistleblower complaint that would stretch on for the duration of his life.

Barnett’s close friend, his lawyer Knowles and his suicide note all point to the stress of his whistleblower action as a factor in his suicide.

“If John would have gotten anything back from the company or the regulating bodies that recognized even partially that he was right, it would have probably given him a little hope, a sense of accomplishment that he was doing the right thing,” said one former colleague and close friend of Barnett, who asked to remain anonymous because he has active whistleblower cases under the name “John Doe.” “But I think it just got to be too much.”

Describing his own experience and Barnett’s, he said, “This is heavy. Sleepless nights, worry, hair falling out because you don’t know what’s coming next.”

“Get a therapist,” he continued. “You’re going to need it.”

Garrick, the Whistleblowers of America chief executive, is pressing Congress to relieve at least one of the burdens on whistleblowers — cost.

Establishing a federal Office of Whistleblower Protection that provides them attorneys at public expense would ensure they’re not bankrupting themselves pursuing their complaints, Garrick said. She also has been lobbying Merriam-Webster Dictionary to rethink the synonyms with negative connotations it attaches to the term “whistleblower,” such as “fink,” “rat” and “snitch.”

Before she launched a nonprofit to support whistleblowers’ mental health, she was a whistleblower herself. She felt the emotional strain common among whistleblowers but still fought a lonely battle with the Veterans Affairs Department, without an attorney’s help, over failures in its suicide-prevention services and prevailed.

Devine called whistleblowing an unforgiving process that can push personal and professional lives to careen out of control.

“It’s horribly stressful,” Devine said. “Whistleblowers are at the crossroads of the contradictory values we’re raised with in this country: It’s good to be a team player, but it’s not good to be a sheep.

“We trust rugged individualists and don’t like rats or squealers, but we also don’t respect people who look the other way. These are incredibly fundamental contradictions in people knowing who they are when it really, really counts.”

Before a fierce, fast infection killed Dean, 45, on April 30 in Wichita, he was showing signs of physical and mental fatigue common among whistleblowers, according to Paredes. They’d worked together at Spirit and became kindred souls who bonded over their commitment to quality in the face of constant pushback.

Dean’s life as a second-generation employee who followed his father to the hometown aerospace manufacturer mirrors many in the greater Seattle area. He worked at Spirit from 2019 to 2023, when he was terminated for missing manufacturing flaws during an inspection. Before that, he’d blown the whistle on improperly drilled holes in the aft pressure bulkhead of the MAX, but said management did nothing.

Dean’s integrity earned him the respect of like-minded colleagues, including Paredes. And ultimately, after Paredes left Spirit over his own frustrations with unaddressed defects, it was Dean who inspired him to become a whistleblower.

That wasn’t an easy decision for Paredes, who’d uprooted his family to a different city and left behind his job. He could simply have walked away.

Whistleblowers can pursue their cases anonymously. And that’s how Paredes started out, a nameless face who’d piggybacked on an existing stockholder lawsuit against Spirit to make his disclosure as a witness outside of the FAA whistleblower program. But after Dean’s death, he went public in May.

Paredes knew the stakes, and he felt the intense uncertainty and fear bordering on paranoia that comes with whistleblowing. He encouraged his wife to keep her handgun loaded, and soldiered through his own nightmares and racing heart. But he has persisted by speaking to federal investigators and cooperating in a stockholder lawsuit against Spirit.

“I reminded myself why I’m doing this: The safety of thousands of people who fly in these planes. Compared to my life, that would be a good trade if it meant changes in the way they build these planes. It’s worth the fight.”

Seattle Times data journalist Manuel Villa contributed to this report.

Correction: An earlier version of mischaracterized a Boeing spokesperson’s comments regarding the impact of Sam Mohawk’s complaints.