For nearly five years, Leslie Galloway had been looking for the money to replace the aging gas furnaces at Southwest Youth & Family Services, a behavioral health and education nonprofit in Delridge.

The building’s heating and cooling system had been failing, leaving staff and community members shivering in the winter and sweating in the summer.

Then Galloway, the nonprofit’s senior project manager, found the money it needed — with a catch.

She managed to secure $273,000 from the Legislature for energy-efficient heat pumps, paid with revenue from the state’s fledgling carbon market.

But the program is under attack. Initiative 2117 on the ballot this November would take it down, blasting holes throughout the state’s budget and threatening hundreds of projects or programs intended to help people adapt to climate change and reduce their reliance on fossil fuels.

Supporters of the initiative have portrayed the carbon markets as a cash grab that has led to higher prices of fuel and utilities on the backs of working-class families without evidence that the program will decrease emissions. Some of the state’s largest polluters of greenhouse gases, including fuel suppliers and refiners, buy allowances at the state auctions.

The repeal effort is funded by a political action committee backed by millionaire Republican Brian Heywood. The group has raised nearly $8 million and is also campaigning to eliminate the state’s new capital gains tax, allow people to opt out of a long-term care payroll tax and enshrine access to natural gas into state law.

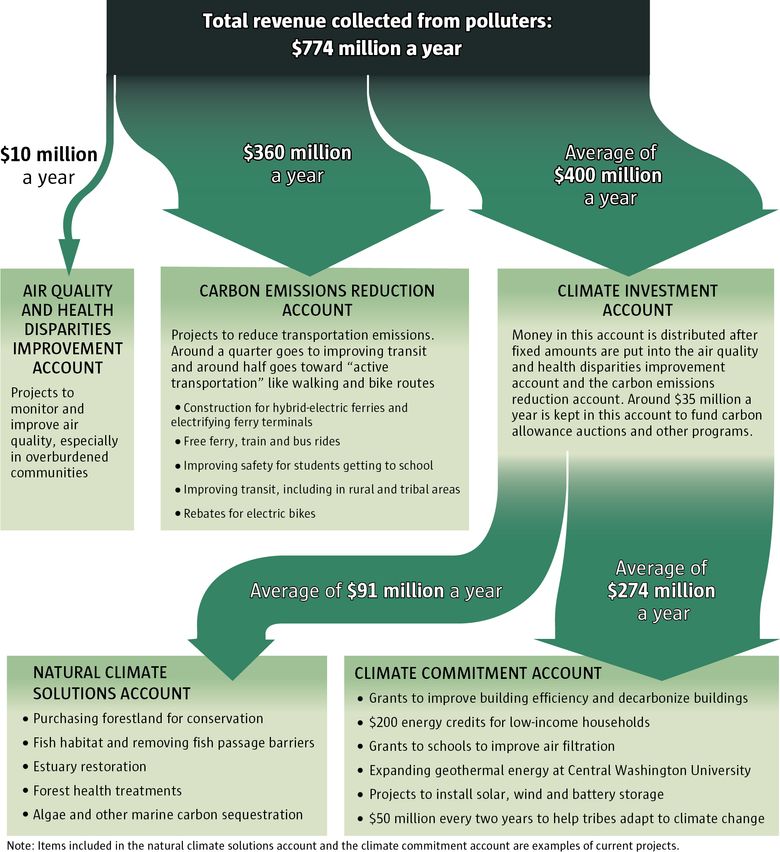

In the past two years, lawmakers earmarked $3.2 billion from carbon allowance auctions to fund electric school buses, solar and heat pump installations, EV rebates and $200 energy credits.

If the initiative backers are successful, state lawmakers would face a budget gap of about $836 million that could affect $1.7 billion of already authorized programs and projects.

The funding Galloway secured for Southwest Youth & Family Services would be lost.

Amid the uncertainty, Galloway instead used county funding for the facility’s new heat pumps, which was going to be used for other upgrades the center needed. The new heat pump couldn’t wait, she said.

“Once I figured out [there was] a climate initiative on the ballot … I knew that there’s a good chance that it might be repealed,” Galloway said.

Much more is at stake. Through June 2029, the carbon auctions are projected to bring in an additional $3.8 billion from polluters on top of an existing $2.3 billion. Some state programs and projects depend on future funding through the same period, totaling $1.8 billion, and would face a shortfall.

The repeal would also upend Washington’s 16-year transportation budget — about one-third of its total funding — stranding projects as large as building new hybrid-electric ferries and as small as rebates for electric bikes.

Elected officials have had many news conferences in the past year touting the positive effect of the Climate Commitment Act, the state law that launched the market. But the real-world implications of the carbon market’s failure might be difficult to understand because of its scale and Washington’s complex budgeting processes.

The Seattle Times followed the money, speaking to Washington budget experts, combing through the state’s finance reports and searching databases of projects to help voters understand how and where this funding flows. It goes to the ferry, bus and train networks, fish-barrier removals and habitat restoration, clean energy development, forest health treatments, building efficiency and energy upgrades.

Voters will soon have the choice about whether to keep the carbon market alive and pumping cash.

The campaigns against and for the initiative have been heating up in recent weeks. The “No on 2117” campaign has raised $13.6 million and has around 300 endorsements, including from investor-owned Puget Sound Energy (the state’s largest utility), REI, Microsoft, the Washington State Sierra Club, 19 individual tribes and science educator Bill Nye.

The repeal would be “catastrophic,” Gov. Jay Inslee said in an interview last week.

“I don’t think you’ve ever seen a more damaging thing to the ability of Washington to serve its citizens,” Inslee said. “… Families don’t have to pay for their bus rides now for their kids. That disappears. The funding for our ferryboats disappears.”

A forest and a people’s dream

The potential effects of a repeal of the Climate Commitment Act go beyond budget sheets. For the Quinault Indian Nation, Initiative 2117 holds hostage an entire forest and an unfulfilled multigenerational dream.

For decades, the tribe has been buying back pieces of its about 210,000-acre reservation after the 1887 General Allotment Act fractured the tribe’s ownership of its land.

Hoping to turn tribal members into “farmers,” the law divided the reservation into individually owned 80-acre parcels, said Tyson Johnston, a Quinault Indian Nation council member. Many impoverished members ended up selling their tracts to timber companies for “pennies on the dollar,” resulting in a checkerboard of ownership across the reservation today, he said.

In the past 40 years, the Quinault Indian Nation increased its ownership of its reservation from 4% to about half, buying back pieces of land here and there with revenue from the tribe’s commercial logging activity, Johnston said.

Earlier this year, the Legislature appropriated $25 million from carbon market revenue for the tribe to buy back an 11,000-acre parcel of the reservation, the last large privately owned portion, Johnston said. But that money would disappear if Initiative 2117 passes.

“It’s pretty devastating,” he said of the threat of the ballot initiative. “This resource [the CCA] is unheard of and to have it go away after all the work that has gone into standing it up is going to be really disastrous to communities like mine that have these very big climate goals and issues.”

By law, 10% of CCA revenue is required to go toward tribally supported uses and projects, and every two years, $50 million must be spent to help tribes adapt to climate change. As part of that, the Quinault Nation will receive $13 million to move two villages away from areas vulnerable to sea-level rise, flooding and tsunamis by funding new buildings and a water tank and pump house.

The Quinault Nation has been treating its forests as a tree farm in hopes of raising the money to buy back land but hopes to eventually manage it to grow cedars large enough for canoes and prioritize habitat for elk and the dwindling sockeye salmon, Johnston said.

The Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians and 19 individual tribes have all signed onto the “No on 2117” campaign to preserve the CCA.

According to the Washington Office of Financial Management, nearly $255 million in CCA funds from the most recent budgets is going toward tribes with an additional $209 million to salmon restoration projects.

The CCA also requires that at least 35% of its revenues goes toward overburdened communities facing the worst effects of air pollution.

Transportation budget

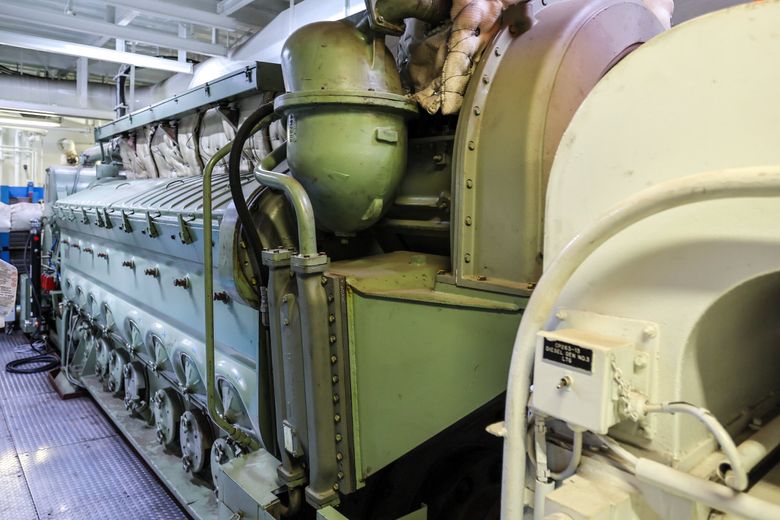

For years, lawmakers have struggled to identify a steady source of money to shore up the state’s aging ferry fleet. Then came the millions of dollars from the carbon market.

At Vigor Shipyards on Harbor Island, the Wenatchee has been sitting in the water next to lounging seals and sea lions for over a year.

The hulking Jumbo Mark II ferry — with space for 200 cars and 2,500 passengers — is being converted to hybrid electric propulsion. On the car deck, tanks of argon gas and forklifts have replaced the passenger cars and trucks that rely on the vessel for access across Puget Sound and two portions of the floor have been removed revealing the engine room underneath.

In the meantime, Washington State Ferries, often described as one of the busiest ferry systems in the world, has been hit by a staffing crisis compounded by a lack of boats. Twenty-one boats are running on a reduced schedule, though at any time up to six boats are out of service for maintenance. A full service includes 26 boats. That has meant regular delayed or canceled sailings and stranded travelers.

Both the Inlandboatmen’s Union and the two unions that represent the workers in the ferry’s engine room and pilots house have urged Washingtonians to vote against Initiative 2117.

One-third of Washington’s 16-year transportation plan, which started in 2022, is funded with CCA money, or $5.4 billion of the $16.8 billion. The money goes toward expanding the state’s EV charging network, building hybrid-electric ferries, bike and pedestrian projects, free transit fares for youths and improving bus service in communities across the state.

CCA revenue is earmarked to pay for around one-quarter of the costs to build new hybrid-electric ferries, up to three conversions, including the Wenatchee, and the electrification of terminals, including the Seattle Ferry Terminal at Colman Dock.

A bet on the future

University of Washington’s battery lab — its recent expansion funded with $7.5 million from the CCA — represents the innovation supporters of the law hope can transition society off fossil fuels.

Over the past seven years, hundreds of researchers with the university, startups and the largest tech companies in the world have used the lab to test battery prototypes for multiple uses, including virtual reality headsets, solar panels and electric cars.

Last week, Inslee and other leaders alongside researchers celebrated the growing ambitions of the lab, tucked beside the University Village shopping complex. During a tour of the facility, a researcher reached into a glove box filled with argon gas, cut open and unrolled a small battery and examined the materials coated onto the foils.

To power a society mostly through renewable energy, not fossil fuels, our battery technology has to improve, said Dan Schwartz, a chemical engineering professor and the director of UW’s Clean Energy Institute.

When the sun isn’t shining on our solar panels, or wind isn’t blowing our turbines, batteries need to fill the gaps, he said.

“In the world of ‘electrify everything,’ we don’t want a cord attached,” he said.

Researchers here and elsewhere are racing to find out how to make better batteries that rely on more abundant materials. They are also trying to understand how to best recycle batteries and value them as they degrade.

Schwartz can’t reveal which companies have come through the lab to mix electrode slurries and examine materials under a microscope, citing contract terms, but says the lab could hold some of the answers we need to stave off the worst effects of climate change.