In 2015, The New Yorker published an article asserting that an earthquake in our part of North America — the inevitable big one — “will spell the worst natural disaster in the history of the continent.” This was something people here didn’t want to think about.

Yet still The New Yorker arrived, bearing the news that, when the shaking begins, “Anything indoors and unsecured will lurch across the floor or come crashing down. … Houses that are not bolted to their foundations will slide off. … Something on the order of a million buildings — more than 3,000 of them schools — will collapse or be compromised. … So will half of all highway bridges … two-thirds of railways and airports; also one-third of all fire stations, half of all police stations and two-thirds of all hospitals. … [The] quake will set off landslides throughout the region. … The sloshing, sliding and shaking will trigger fires, flooding, pipe failures, dam breaches and hazardous-material spills. Then the wave will arrive, and the real destruction will begin.”

The subject of my story is also an earthquake. My region of concern, though, is smaller than The New Yorker’s, which focused on a quake that will ravage a sizable portion of the coastal Northwest. I’m focused on one that will limit itself to ravaging just Seattle and environs.

Trigger warning. I’m about to go into detail about things that might scare people in the Seattle area. Why would I do that? Because a lot of us here read The New Yorker article and then did little or nothing to prepare for an earthquake. That probably will happen in the aftermath of this article, too. Hopefully, though, not for everyone who reads it.

SOME BACKGROUND.

The world as we know it, while it might appear to be unbroken and continuous, is in fact divided into pieces. Geologists call these pieces “plates,” but for me it’s of no use imagining them that way, because it’s around 60 miles from the bottom to the top of one. They’re more like blocks.

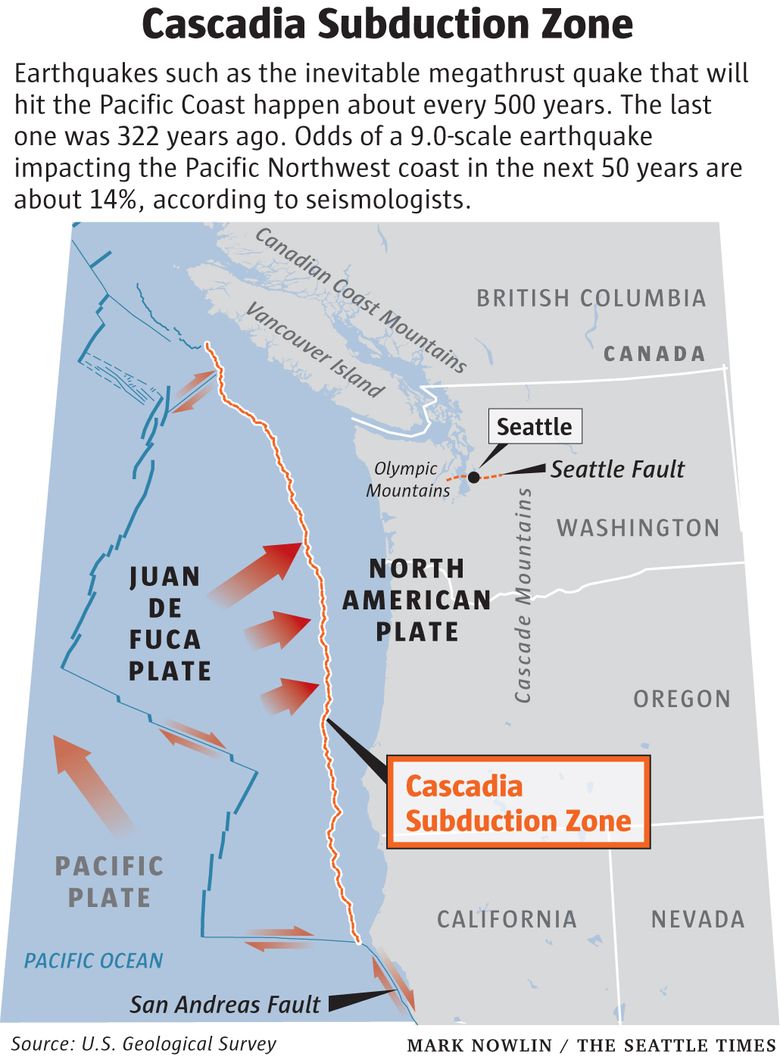

The block Seattle sits on — the North American block — terminates to the east in the mid-Atlantic Ocean and to the west less than 150 miles off our coast. Just west of it is the much smaller Juan de Fuca block. By all accounts, these blocks are impelled by unappeasable forces toward one another. They’re in each other’s way, so something has to give — and does give, recurringly. The New Yorker article describes what will happen the next time something gives at these plates. It illuminates what it means for all hell to break loose because of it.

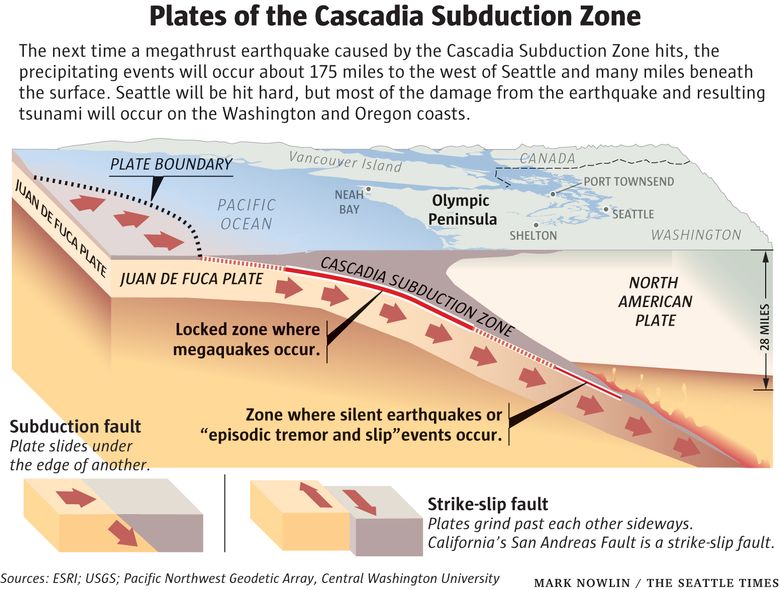

That said, if you live in Seattle, you can take solace from the fact that the precipitating events will occur about 175 miles to the west and many miles beneath the surface — in other words, far enough away to mitigate their worst effects. Seattle’s hell will not include as much violent shaking — or tsunami inundation — as will occur on the Washington and Oregon coasts. Still, when the shaking is over and the sea returns to normal, Seattle will be in a bad way.

But that’s The New Yorker quake — a regional cataclysm that will include our city as it lays waste to many thousands of square miles. The one I’m failing, so far, to write about, when it occurs — as it must — will probably be called the Seattle Quake, or the Great Seattle Quake, for an obvious reason.

BETWEEN 2012 AND NOW, the 10 largest earthquakes in the world all have been of The New Yorker variety, otherwise known as megathrust quakes. In every case, the precipitating events occurred deep beneath a seafloor. One quake started under the Indian Ocean, and one under the Sea of Okhotsk. The other eight all started under the Pacific Ocean. The combined death toll from these 10 quakes was 137. If that doesn’t seem low to you, consider that the biggest earthquake of 2011 — also a megathrust — killed almost 20,000 people.

Why was one quake so much deadlier than the others? The 10 largest quakes of the past 10 years happened so far from land, both vertically and horizontally, that by the time their effects reached inhabited areas, they were muted enough not to kill in large numbers. As for the 2011 quake — sometimes called the Great East Japan Earthquake — it too started far from land, but its effects included a devastating tsunami. When a quake begins where the Earth’s blocks are in confrontation, its capacity to kill greatly hinges on this element: a tsunami. If the quake doesn’t generate a significant one, it probably causes few casualties. If it does generate a significant tsunami, the death count can be high. That’s what happened in 2004, when a quake starting deep beneath the Indian Ocean killed more than 225,000 people in 14 countries.

Seattleites can feel confident that when the next megathrust quake happens in the coastal Northwest, Puget Sound isn’t going to be roiled the way the Pacific was roiled by the Great East Japan or Indian Ocean earthquakes. There will be plenty of suffering, and certainly some deaths, but no apocalyptic lethality.

I DON’T WANT to undermine the warning The New Yorker gave us. The inevitable megathrust quake it describes is worthy of our anxiety, not just because of the horrors it will entail but also because it could happen soon. Quakes of this sort occur in our region on average every 500 years. The last one happened 322 years ago, and the one before that about 1,300 years ago. You might choose to focus on the fact that about 1,000 years passed between the two, but only if you’re an insistently cup-half-full person. For everybody else, it might be chastening to hear that the interval between the quake of 1,300 years ago and the one before it was around 320 years.

It should be said these megathrust quakes generally rate very high on the Richter scale, which has been replaced by the “moment magnitude” scale. Scales like these are meant to say something about the relative strength and intensity of earthquakes, and for geologists, they do so usefully. For the rest of us, though, the scales can be misleading in a way that can have consequences.

News reports on earthquakes emphasize magnitude. Insistently, they call our attention to the scale of what happened. Alongside descriptions of death and destruction, they make use of numbers — how many dead, how many injured, how many homeless, how many buildings brought to the ground. Looming over all of that stands a one-digit whole number followed by a decimal, like 9.2 or 6.2. Those are moment magnitude scale numbers.

The moment magnitude scale suggests phenomena that get more intense by steady, equal degrees, one-tenth of a whole number at a time. In other words, it suggests that a 9.2 earthquake would be about a third more intense than a 6.2. That isn’t how it is, though, because the moment magnitude scale is logarithmic. A 9.2 is in fact many thousands of times more intense than a 6.2.

If that were all there was to it, it might not matter much. We would misunderstand the meaning of numbers in a way that did us little harm. Unfortunately, though, there’s a more troubling problem. Scale numbers ignore a quake’s depth and location, which turn out to have very much to say about its potential for destruction.

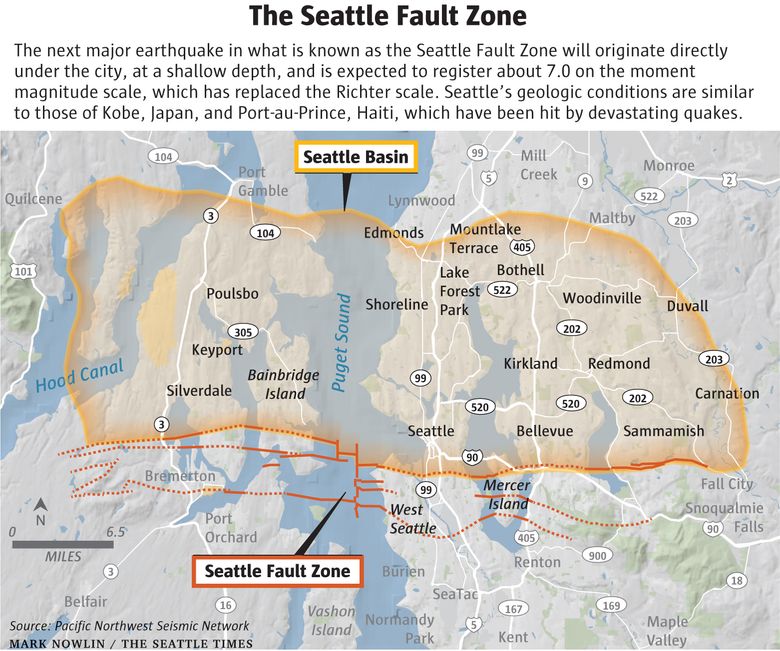

Again, the next major megathrust quake here will originate well under the Pacific seafloor. The next major quake in what is known as the Seattle Fault Zone, though, will originate directly under our city at a shallow depth. The megathrust quake will be of the 9 variety; the Seattle quake will be more like a 7. Don’t be comforted by your take on those scale figures (even though it’s true that, if you do the math, a 9.0 turns out to be more than 1,000 times more powerful than a 7.0). A 7.0 quake in 2010 killed more than 300,000 people in Haiti. That one originated 6 miles below the surface. Its epicenter was 16 miles from Port-au-Prince, a city about Seattle’s size.

THESE THINGS AREN’T easy to think about rationally. Most of us, because we prefer certain outcomes, have trained our brains to lead us to them. Our conclusions come first — for example, “No major earthquake will happen during my lifetime” — followed by arguments in support. Willfully, then, we confirm our biases. After that, we bury our heads in the sand.

The odds of a 9.0 quake impacting the coastal Pacific Northwest over the next 50 years is said, by seismologists, to be about 14%. Maybe you’ll take those odds and bet against it happening. They’re not terrible, after all: about the same that an NFL kicker will miss a 37-yard field goal. On the other hand, about the same odds — 15% (as estimated by The New York Times on Election Day morning, 2016) — were attached to a Donald Trump triumph over Hillary Clinton.

As for the Seattle Fault Zone, the odds are 5% for a 6.5 quake in the next 50 years. You might take those odds, too, and bet against it happening. And by betting against it, I mean not preparing for it. Every time an earthquake happens, most people are surprised.

GEOLOGY ONCE MORE.

The Juan de Fuca block rotates in the manner of a cylinder. As it turns eastward on its downward arc, it tries to grind through the neighboring North American block. The blocks’ zone of interpenetration lies beneath the Cascade Range, where intense pressures produce volcanic peaks like St. Helens, Baker and Rainier. More to the point, though, the leading edge of the North American block, driven west, carves material off the sinking Juan de Fuca block and piles it as rubble. This is where we live in Western Washington — on top of Juan de Fuca block rubble, intermingled with a momentous amount of material that has been sliding off the North American block for a long time, all of it now compressed nearly solid and subject to its own set of earthquake-causing forces.

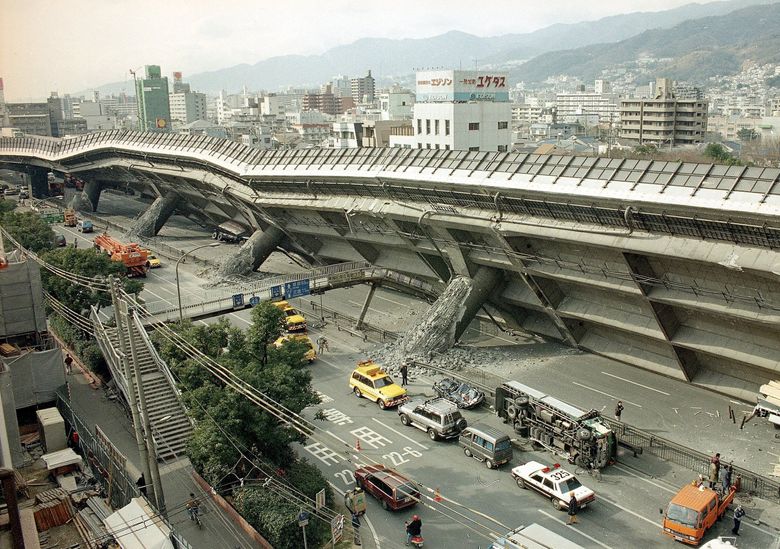

The Seattle Fault Zone lies within this admixture and, like what underlies it, is composed of blocks pressing against each other. About 40 miles from east to west and 5 miles from north to south, it includes a major fracture running just south of downtown, and another fracture that’s under a succession of North Seattle neighborhoods. The zone lies at a depth of 2 to 4 miles, and is prone to earthquakes like the one in Haiti, or like the 6.9 earthquake in Kobe, Japan, in 1995, that killed thousands of people and did more than $100 billion worth of damage. As it turns out, geologic circumstances under Seattle are much like those under Kobe.

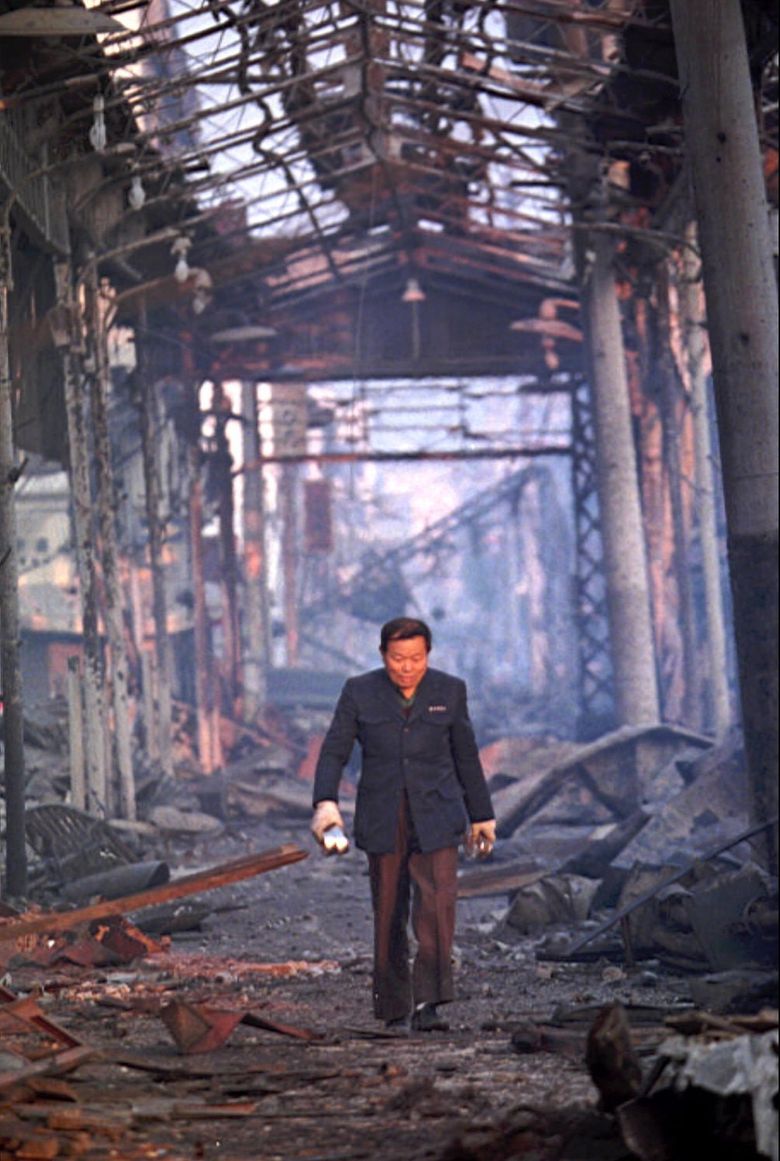

What happened in Kobe was catastrophic. Of the approximately 6,400 people who perished in the city and its environs, at least 80% died trapped in rubble. Some people were crushed, some suffocated and some died in firestorms. Fortunately, it was before 6 a.m. when the shaking started, so most places of work were empty. That said, 240,000 homes were damaged, and more than 40,000 people were injured. Hospitals were overrun. It was January; the weather was freezing. Amid this, about 300,000 people were suddenly homeless. I won’t continue in this vein, but I will say that all of it happened in a country widely considered state-of-the-art when it comes to earthquake preparedness. And that the quake’s epicenter was 12.5 miles from the city, and 10 miles beneath the surface.

SEATTLE FAULT ZONE quakes begin as ruptures. At some point along one of its faults or fractures — by which I mean a seam where two blocks shove against each other — the pressure of opposition becomes too great, and one or both blocks suddenly move. When that happens, the energy that’s unleashed spreads in all directions, but most dramatically along the fault itself, which tears.

It might help to imagine two blocks meeting on a diagonal line: When the fault ruptures, two things can happen. One of the blocks can climb. Or one can climb while the other sinks.

A 2005 model for a 6.7 Seattle Fault Zone quake, made by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, predicts ground rupture of about 6 vertical feet from Harbor Island to Issaquah. Meaning, I guess, that if you survive the shaking, and can figure out how to get across Lake Washington, you could walk 15 miles or so along the wall of a freshly opened scarp.

There’s more. Power, water, sewer and gas lines will be severed, as will the cables and wires that make internet connections possible. Our hospitals will be overrun, and our grocery stores will empty. I’ll add more: firestorms, hazardous material spills, downed bridges, landslides by the thousands. I agree with you — I sound like The New Yorker here.

In the aftermath of its article, The New Yorker heard from readers in our region who were interested in preparing for the next megathrust quake. To its credit, it followed up that same month with an article called “How To Stay Safe When the Big One Comes,” which ended, “Take some basic steps to protect yourself, work to draw attention to those issues that demand collective action — do that, and you need not be overly scared either.”

I would add only that it makes sense to take steps now, because by putting them off you increase the risk that your motivation will fade to nothing. We have a list of some things you might do, along with practical advice and useful links that can help you take action.