By

The struggles of Seattle’s downtown to recover after the pandemic have rightly been blamed on some key factors, such as the inability of the city to get control of public safety there.

But new data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows just how much the change in how we work has affected Seattle — more so than any other city in America.

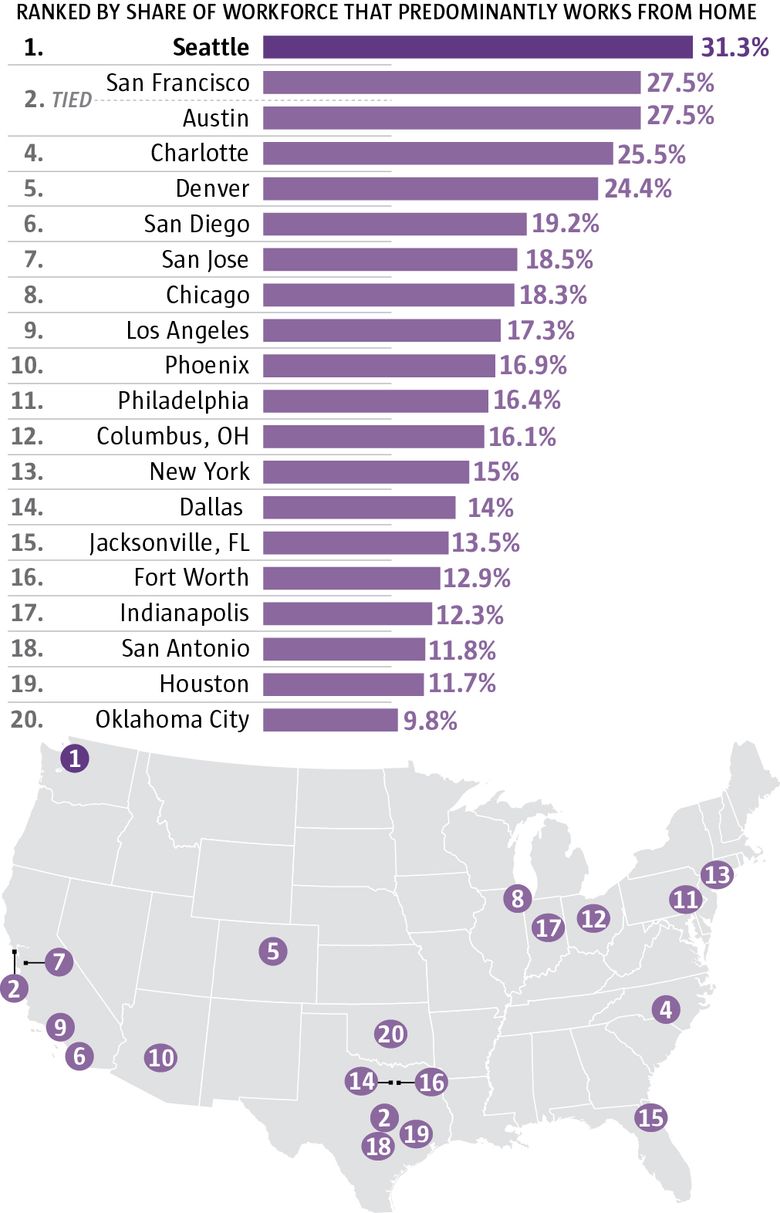

Seattle has led the nation in remote work among the 20 largest cities, for the five-year period from 2019 through 2023, new census figures show. The gap between Seattle and many other cities is surprisingly wide.

The share of Seattleites working from home for their predominant commuting method is twice as high as it is in New York City, the data from the bureau’s American Community Survey shows.

In Seattle, 31.3% of the workforce has been working mainly from home – more than 140,000 employees. That’s up from just 7.2% in the five-year period before the pandemic dislocated everything. It’s nearly as many as the 170,000 Seattle workers who still commute the old-fashioned way, solo by car.

The Census Bureau’s five-year data includes one year before the pandemic, then the pandemic itself and also the two years after it had begun to subside. It gives the most complete picture to date of what happened with the workforce in various cities.

The bureau also releases one-year surveys that give a more up-to-date picture. In that data, through the end of 2023, Seattle ranks second for remote work among big cities, at 28.5%, behind only banking-dominated Charlotte, N.C., at 29.7%.

Workers have been returning to offices, slowly, pretty much everywhere. But inside Seattle city limits, remote work remains high despite Amazon’s push to get its entire workforce back, starting three days per week in May 2023, and due to head to all five days starting Jan. 2.

After Seattle, the next highest cities for work from home were Austin, Texas, (27.5%), San Francisco (27.5%), Charlotte (25.5%) and Denver (24.4%), the five-year data shows.

The data comes from asking workers ages 16 and up how they got to work in the previous week – drive alone, take public transit, walk, work from home, and so on. People were asked to select what they did on most days, so someone working from home might still also go into the office at times and vice versa.

Researchers have also begun teasing out the impact a big switch to remote work is having on cities.

One study from MIT found that remote work did lead to an easing in traffic. It wasn’t as much as expected, though, because remote workers tend to run errands throughout the day in their cars.

Most strikingly, they found the remote work trend came mostly at the expense of public transit. Ridership on buses and trains declined more than twice as fast as car travel in response to remote work.

The new census figures show this for Seattle. As remote work more than quadrupled here since prepandemic, the share of workers who commute alone in cars has dropped about 21%. But those taking public transit plummeted 36%.

The researchers concluded that transit agencies “need to adapt” to have more noncommuting trips that are less peak-focused, mirroring the all-day flexibility of the new work environment. If remote work starts to increase again, it may call into question the planned expansion of expensive, fixed-guideway transit systems such as light rail.

In Seattle, the lack of safety downtown and on transit may also be propping up remote work. It’s a tougher sell for bosses to argue you must commute back to the office when the city can’t keep the bus stops open in Little Saigon, or the Metro drivers safe from attack.

Researchers at Stanford University found that working from home is hugely popular but is also exacerbating the siloing of society. It’s for the well-off and highly educated (hello, Seattle). Lower-paid, less-educated workers often don’t even get the option. “The Great Work-from-Home Divide,” they called it.

“Further sorting and segmentation is likely to further erode productive social cohesion,” one researcher depressingly predicted.

While most of the focus is on what’s happening to workers and companies, in Sacramento, Calif., they hired a team of consultants to assess the economic impact on the city itself.

The findings, the team wrote, “were astounding, far outweighing the initial projections of loss to Sacramento through the downtown core alone.” The real estate losses alone were projected in the billions. There’s also the lost spending of all those workers who used to be downtown. The study concluded that downtown Sacramento – which has a remote work rate only about half of Seattle’s — is facing at least $4.4 billion in economic losses due to work from home.

Seattle hasn’t done such a study — it should. We could at least then face the new reality head on.

As it is, the Downtown Seattle Association says there are still more than 500 vacant storefronts in the downtown core. Some of those might come back if public safety improves. But as the Sacramento study showed, a lot of the customer base is simply hanging out in other neighborhoods now.

The massive loan defaults of top downtown developer Marty Selig on some of his Seattle office buildings may be a signal of what’s to come.

Stanford economics researcher Nicholas Bloom predicts the return-to-office movement, currently being pushed by Amazon and other companies, is going to stall out. Remote work has dipped and plateaued postpandemic, but it will inevitably rise again in the future, “driven by ever-improving technologies.”

“For cities, this will mean increasingly moving from a place of work to a place of leisure and consumption,” he writes. The key to that, he says, is “good public infrastructure, and improved services like education and police. To attract residents, shoppers, and diners, cities must provide appealing services and control crime.”

Seattle is trying on those fronts, though not all that consistently — or effectively.

Much more is needed. Maybe Amazon’s drive back to the office will rejuvenate things. But one idea is to forget about attracting new big employers or mall-like retail outlets for now, and instead go small.

Mark Hinshaw, a former Seattle Times architecture writer who now lives in Italy, says in Europe the government sometimes jump-starts the street by stepping in to take over the leases of distressed buildings, then renting out spots to small businesses.

It’s often why streets in Italy and cities like Vancouver, B.C., are lined with “small, quirky businesses” rather than large chains or services like banks, he writes. The government has incentivized the little guys to come in.

“Building owners need to get over the idea they’re going to get a big bank (or) a large national brand clothing store,” he wrote earlier this year on Post Alley. “It’s going to take marketing these spaces to small locally owned businesses — and at significantly lower rents.”

We’re now nearly five years on since the pandemic first hit, and downtown still is pocked with hundreds of vacant storefronts. Some targeted effort like this is desperately needed. Or the downtown of America’s remote work capital may itself feel pretty remote for years to come.