CHERRY POINT, Whatcom County — Thick steam billowed from a series of towers and pipes, intricately woven together to form a powerhouse of the region’s energy production and Washington’s largest oil refinery.

BP’s Cherry Point facility, which belched more than 2 million metric tons of climate-warming gases into the atmosphere in 2021, is in a phase of transition as state laws and incentives push the oil giant away from fossil fuels.

Last week, BP representatives hosted a tour of the company’s evolving facility. A new silver, silolike vessel processes “renewable diesel,” made from a combination of beef fat, soybean oil and other used cooking oils from the Western U.S. and Canada. Refinery leaders are also now drawing up plans to produce lower-carbon aviation fuels.

The oil company has goals of producing less carbon emissions than it removes from the atmosphere by 2050. It was among those advocating for a market-based approach to reduce carbon emissions from the state’s biggest polluters.

BP helped pass what is now today’s Climate Commitment Act, which requires the state’s largest-polluting businesses or institutions to pay for their climate-warming pollution and puts a statewide cap on emissions that will gradually ratchet down over the next 27 years.

“We were saying, yeah, we can do this,” said Tom Wolf, senior government affairs manager for BP’s West Coast subsidiary. “This will drive the innovation that it needs. It’s timely and fair, and allows for innovation and opportunity and capital investment.”

The program requires the state’s top polluters, like oil companies, to pay for emissions by buying allowances at quarterly auctions. Each allowance represents 1 metric ton of emissions. Over the course of seven three-year periods, state officials will reduce the number of allowances sold, thereby reducing the amount of emissions allowed in the state.

Some oil companies began passing the cost of those pollution allowances on to customers at the pump.

An invoice reviewed by The Seattle Times showed that an oil company had added a line item listed as “cap at the rack,” a reference to the state’s new program, of 52 cents per gallon of diesel purchased by a fuel distributor, which trucks wholesale fuels to gas stations, construction companies and homes around the state.

Washington’s climate laws are also forcing the state’s largest refinery to invest in lower-carbon fuels, as a step toward a future with little or no emissions.

While BP is not yet drawing up plans to decommission its fossil fuel infrastructure, company leaders and state lawmakers see some of these lower-carbon fuels as critical to the regional energy transition.

Some environmentalists worry it’s too little, too late.

The Paris Agreement set out an international framework to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), intended to prevent the worst consequences of climate change: flooding, wildfires, drought, heat waves and species extinction.

A recent United Nations report card said the current global climate pledges have put the world on track for about a 2.5 degrees Celsius rise by 2100.

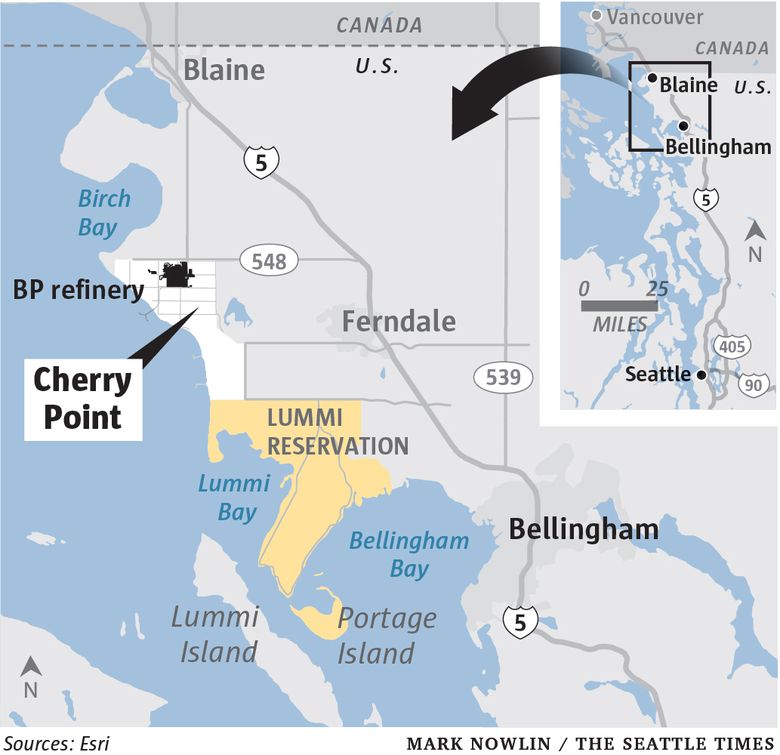

For thousands of years, Lummi people fished at present-day Cherry Point, or Xwe’chi’eXen. Since colonization, the shore of the deep water cove has exploded with dirty energy production and other manufacturing, supporting an aluminum smelter, oil refineries and a liquefied petroleum gas facility.

BP’s Cherry Point refinery is one of the youngest in the country, coming online in 1971. Today, it can process 250,000 barrels of crude oil each day, mostly coming by pipeline from Canada, by rail from North Dakota and globally at a nearby shipping dock.

It’s the No. 1 supplier of jet fuel to local airports in SeaTac, Portland and Vancouver, B.C. It’s also Washington state’s second-largest emitter, according to the latest data.

After the state passed its carbon-pricing program, and a low-carbon fuel standard, BP spent about $270 million on efficiency upgrades at the facility that was estimated to reduce emissions by about 7%. The emissions data hasn’t come in since the upgrades were completed.

Today, the company uses “gray” hydrogen, which is produced with natural gas. Refineries typically use hydrogen to reduce the sulfur content in crude oil.

For the production of lower-carbon aviation fuels, the company would like to pursue “green” hydrogen, an electricity-intensive process that splits water molecules into oxygen and hydrogen.

“Sustainable aviation fuels” are biofuels often made in part with cooking oils. When combusted in jet engines, the fuels are anticipated to reduce emissions as much as 80%.

If the company was not using green hydrogen to produce sustainable aviation fuel, it would actually raise the refinery’s carbon footprint, said Wolf, the company lobbyist. Because the state’s climate laws are calling for emission reductions, the facility is being forced to look to green hydrogen.

Optimistically, the production of these lower-carbon aviation fuels could be underway by 2028, said Eric Zimpfer, the vice president of refining at BP Cherry Point. That estimate includes the design, engineering, permitting and financing processes.

In Washington state, BP has access to incentives to fund this transition every step of the way.

So-called sustainable aviation fuels have emerged as the most realistic way to decarbonize the aviation industry, said state Senate Majority Leader Andy Billig, D-Spokane. Electric or hydrogen-fueled commercial jets still appear to be a distant goal, he said.

A bill sponsored by Billig created tax credits that provide subsidies of up to $2 per gallon for the low-carbon fuels, which is two to five times more expensive than regular jet fuel that currently costs about $2.17 per gallon.

To some environmentalists, sustainable aviation fuels remain a “dangerous fantasy,” they wrote in a Times op-ed. Fossil fuels will continue to be refined and later combusted as part of the product.

Environmental justice groups have long opposed the state’s carbon-pricing legislation, pointing out that the carbon market itself is prioritized over cutting emissions.

In California, environmental justice advocates have noted the Golden State’s program has largely failed to improve the lives of low-income people of color living near the polluting companies participating in the carbon markets.

The city of Seattle in 2018 found that jet fuel accounted for 24% of its overall carbon emissions.

Studies have found South Seattle communities, in Seattle-Tacoma International Airport’s flight path, and surrounded by industrial facilities, have higher rates of sickness and death than other parts of the city.

Communities of color and those with lower incomes largely bear the brunt of the state’s biggest polluting companies.