This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network and The Seattle Times, with support from the Investigative Journalism Fund. Sign up for Seattle Times newsletters and alerts and ProPublica’s Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Times Watchdog stories dig deep to hold power accountable, right wrongs and create change. This work is made possible by The Seattle Times Investigative Journalism Fund. Donate today to support watchdog journalism in our community.

In its early days as a major aircraft manufacturer, Boeing was remarkably open about toxic chemicals flowing from its factory into the neighboring Duwamish, Seattle’s only river and a longtime source of food, tradition and culture for Indigenous people.

In fact, the company described the Duwamish River as “a natural collector for Boeing’s fluid wastes” in a 1950 magazine article Boeing produced for its employees. Boeing said at the time that it had a handle on the situation — asserting, for example, that some of its most volatile waste would be neutralized by chemicals released by other polluters.

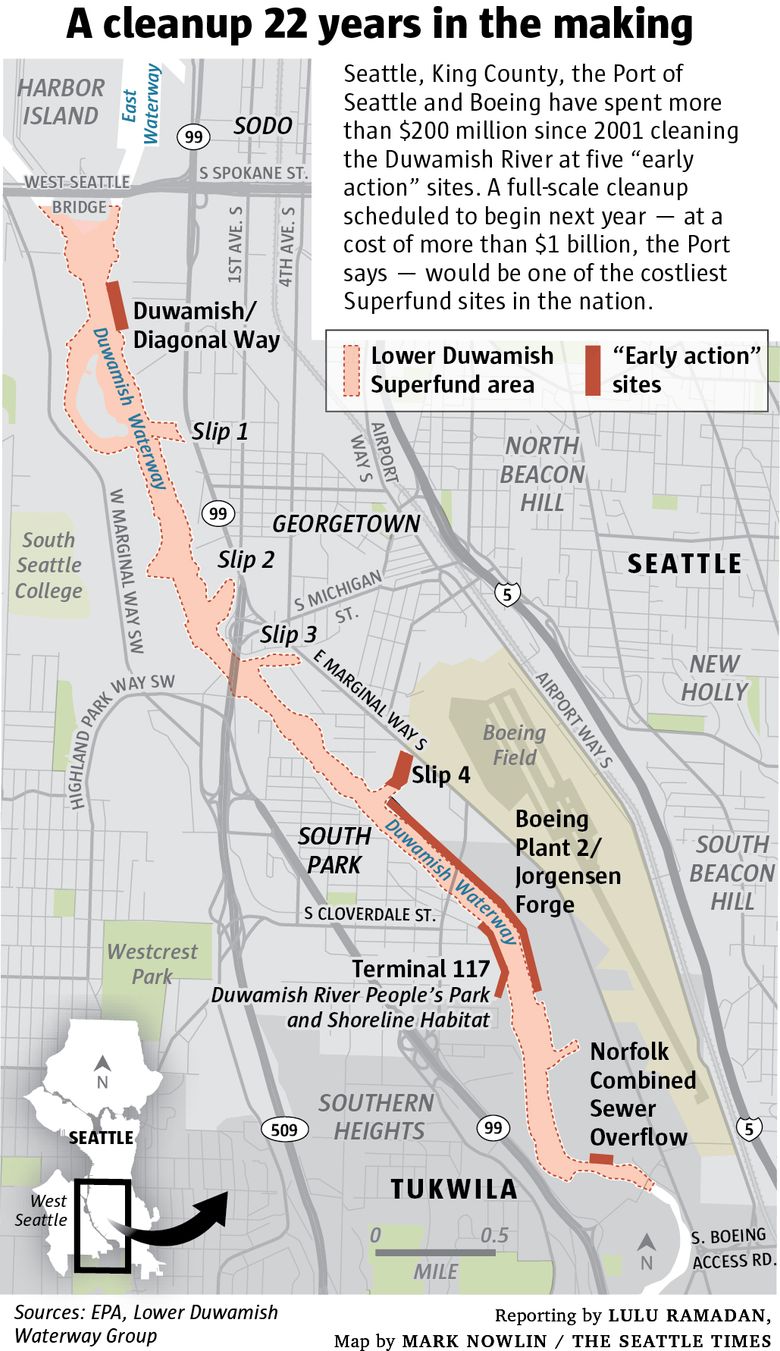

Today the waterway is among the nation’s most contaminated, a full-scale cleanup is scheduled to begin next year, and Boeing is deep in negotiations over how to split the cost with other leading landowners on the river: the city, adjoining King County and the Port of Seattle.

As with most negotiations conducted under the nation’s Superfund cleanup law, the parties agreed long ago to keep details of their talks secret. But a short-lived lawsuit, filed by the Port last year and withdrawn in June, offered a glimpse of a staggering dollar figure that’s never been part of the public discussion.

In court papers accusing Boeing of trying to slough off its share of the cleanup bill, the Port said the total cost could top $1 billion. The sum is more than double any estimate previously made public, and it would make the Duwamish one of the nation’s costliest cleanups on record. Government websites still put the cost at about $340 million.

The dollar amounts alluded to in the 2022 lawsuit point to a high-stakes and largely hidden deliberation between the region’s biggest government players and a major company born in Seattle more than a century ago.

Whatever the parties agree to, taxpayers may never know whether the cost split was fair because how the decision was reached is intended to remain secret.

This month, in response to questions from The Seattle Times and ProPublica, Boeing said it was the Port that is refusing to do its part.

“We were extremely disappointed in the Port’s refusal to pay its equitable share of the cleanup and in their decision to subsequently file and then dismiss a lawsuit,” the company said in a written statement.

Boeing declined to comment on the private negotiations or disclose the exact amount it agreed to pay, but it said that the company expects to spend “hundreds of millions of additional dollars.”

This summer, Boeing joined with the city and county in issuing a separate statement saying the lawsuit’s allegations do not affect their “ongoing and lasting commitment to restoring the water quality of the Lower Duwamish for people, salmon, and orcas.”

“The City of Seattle, King County, and Boeing will continue to work to advance the cleanup to benefit this generation and those that will follow,” the joint statement reads.

The Port continues to claim, as it did in its lawsuit against Boeing, that negotiations could saddle taxpayers with “tens of millions of dollars” in costs for which the company is liable.

Meanwhile, people who have waited for the Duwamish to be restored say they worry about the lack of information available to the public.

“The reality is there isn’t a lot of transparency,” said Paulina López, executive director of the Duwamish River Community Coalition, a federally recognized task force dedicated to representing community interests in the cleanup.

What advocates say worries them even more is the possibility that an impasse over who pays, two decades into the river’s Superfund listing, will mean yet further delays in restoring the river.

“Toxic to eat”

Two centuries ago, as white settlers began to develop the land, Native tribes successfully negotiated for their fishing rights on the Duwamish River to preserve a cultural touchpoint and vital food source. The city of Seattle eventually recognized the river’s value as a pathway for transporting cargo. It scraped away the winding river’s marshy banks, straightened its natural bends and dredged its floor.

What was once a complex ecosystem of mudflats, native plants and spawning fish became a sprawling industrial corridor.

Boeing found a home along the Duwamish in 1916, launching an operation from an abandoned shipyard where it built seaplanes. In the 1930s, the company developed the nation’s first four-engine bomber, and the federal government eventually ordered about 7,000 B-17s over the course of World War II. By the end of the war, Boeing’s plant along the Duwamish expanded to nearly 1.7 million square feet.

It ultimately became one of the largest landowners in the industrial district, but publicly owned facilities also contributed toxins: water runoff tainted with chemicals from the city’s steam plant, pollution from the Port’s cargo terminals and unfettered sewage dumped from King County’s wastewater system.

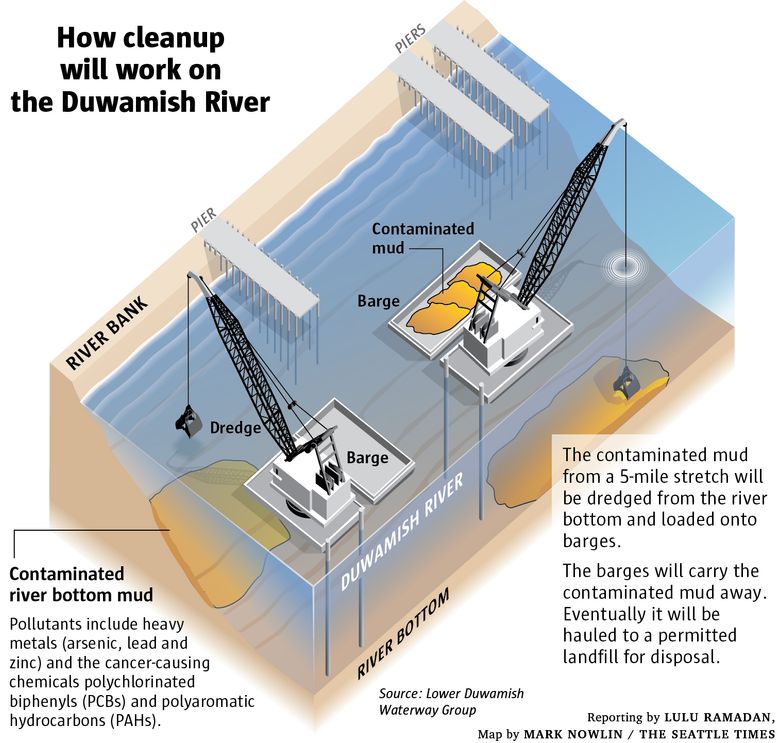

The river is now contaminated with heavy metals and cancer-causing chemicals, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

Along the river now are large health advisory signs warning the public not to eat bottom-feeding fish and to limit consumption of certain salmon, a warning system King County calls “Fun to Fish, Toxic to Eat.” Even direct contact with river mud is a risk, the state health department warns. Tribal fishing, protected by an 1855 federal treaty, continues along the river despite declining fish populations and public health warnings.

Some of these contaminants can be traced to Boeing’s plants along the river, which is why the federal government has named it as one of the major responsible parties.

Boeing’s 1950 magazine article, brought to light in the Port’s lawsuit, described its efforts to curb pollution, but the company openly acknowledged that “any unrestrained liquid emptied on the Boeing premises is bound sooner or later to get into the Duwamish.”

Tracy Collier, a toxicologist who worked at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center for three decades and who read the magazine article at The Times’ request, said that it makes legitimate scientific arguments about how pollutants can be diluted and neutralized, but that it’s impossible to tell from the description alone whether Boeing successfully reduced the amount of contamination.

It’s also important to note, Collier said, that some contaminants now found in high concentrations in the river weren’t on the radar 70 years ago. Boeing is one of the parties known to have contributed PCBs, for example, according to the state Department of Ecology.

“We didn’t know in 1950 that PCBs were going to be persistent and as toxic as they are,” Collier said. The chemical wasn’t banned by the EPA until the 1970s.

Boeing said in a statement that its article described disposal practices that were the industry standard at the time. The company added that it proactively took the steps described in the article before federal and state environmental laws took effect.

In early 2000, a survey by the EPA revealed that the river was eligible for Superfund designation, meaning it was one of the most polluted sites in the country.

The Superfund, created by Congress in 1980, was meant to address the nation’s legacy of toxic industrial waste by establishing a process to pay for cleanups. It was also known to result in costly legal battles. The Port, city, county and Boeing hoped to divvy up the tab and clean the river without triggering the Superfund process.

“They were worried about the stigma it would cast on the city, and some believed that they could clean the river up faster and better without EPA dogging their efforts,” BJ Cummings, community engagement manager for University of Washington’s Superfund Research Program, wrote in her book “The River That Made Seattle,” which details the Duwamish’s history.

But federal environmental regulators needed to sign off. They wanted an agreement that would allow them to go after polluters for damage up to three years after completion of the cleanup, just as they could under the Superfund.

Boeing would not agree. The company told a Times reporter in 2000 that it caused only a small part of the pollution and was worried that it would be stuck with a big share of the cleanup.

“We couldn’t sign the agreement without assurances that there would be an equitable outcome,” a Boeing spokesperson said at the time.

The Duwamish River landed on the national Superfund list the following year.

Behind closed doors

With EPA oversight, the three government agencies and Boeing agreed to equally front the bill for testing the river water, surveying the contamination and planning the cleanup. They planned to eventually redistribute the costs based on responsibility for pollution, a canon of Superfund law known as the “polluters pay” principle.

What happened next is hidden by an agreement signed by the parties to keep the process private.

This type of process was first created under the Superfund to make it easier for private companies to discuss business practices and liabilities frankly with the EPA. The goal was to have polluters agree among themselves on how to cover cleanup costs.

But in this case, the polluters in question include three local governments. Every dollar that Boeing doesn’t pay could end up the responsibility of Seattle-area taxpayers.

Even where the negotiators meet, who is in the room and what evidence is considered are secret. But court documents and interviews offer a few intriguing details about the process so far.

In 2014, the group hired John Barkett, an experienced environmental lawyer from Florida, to act as an outside allocator and deliver a report suggesting how the parties should divide the costs.

Court documents Boeing filed seeking to put the Port’s lawsuit on hold describe parties exchanging historical records, responding to detailed questionnaires, providing expert reports, taking depositions and attending meetings to discuss costs.

Barkett provided his final report to the parties last year and hasn’t been involved in the process since, he told The Times and ProPublica, declining to speak in detail about the Duwamish River or the allocation. The news organizations asked the Port, the city and the county for a copy of the report, but all declined, citing the nondisclosure agreement among the parties.

Both King County and the city said in separate statements that they believe the ongoing allocation process has been “thorough and fair.” Both said they plan to make their individual shares public once the process wraps up, but neither one plans to release the full report. The reason, the city wrote in an email, is that it “contains each party’s sensitive operational and financial information.”

The allocation report is nonbinding, meaning the parties can adjust or reject Barkett’s suggested breakdown of costs. Court documents show that on July 11, 2022, Boeing agreed to an undisclosed share of the cost. The Port of Seattle filed its lawsuit eight days later.

“Boeing has gleaned billions of dollars in profits over the past several decades partly through externalizing its waste disposal costs by dumping wastes into the Lower Duwamish River,” the Port said in its claim.

The Port said it had negotiated diligently for eight years, but that the cost split on the table would force the Port to “redirect taxpayers’ funds from projects and programs that benefit the public,” threatening environmental justice initiatives, “employment funds” and projects aimed at expanding public access to the river.

The Port’s allegations opened old wounds for tribal leaders who have fought for decades to hold the river’s polluters accountable, said Leonard Forsman, chairman of the Suquamish Tribe, which has fishing rights on the river.

“I know that industries along the river made a lot of money at the expense of our waterway,” Forsman said.

“They were well aware of what they were doing,” Forsman said of corporate polluters, adding that Boeing and other companies “have to acknowledge that and take responsibility.”

Port officials withdrew the lawsuit in June, saying that “litigation is not the most efficient path to resolution at this time.” Any further discussions would once again take place behind closed doors.

The Duwamish River Community Coalition, which represents the public’s interests in the cleanup, feels shut out, said Jamie Hearn, a lawyer for the coalition. “We don’t have access to a lot of information, and responsible parties are very careful to only release certain details,” Hearn said.

Still, as frustrated as Duwamish activists may be about the lack of transparency in the Superfund process, they want to avoid delaying the cleanup any further.

The community is less concerned with who pays the bill than with making sure the cleanup happens on schedule, said López, the executive director of the community coalition.

“We’ve already waited so long,” she said.

Taxpayers pick up the tab

What is known about the Duwamish cleanup publicly is that it has already cost a lot — and U.S. taxpayers have picked up a big chunk of the bill so far.

The Lower Duwamish Waterway Group, a private-public partnership between Boeing and the three government agencies, says it has already invested more than $200 million in early cleanup projects and habitat restorations along the river, targeting its most polluted parts. These actions have reduced the amount of PCBs in the river’s sediment by half, according to the group.

Boeing said in a statement that it alone invested $115 million on an early cleanup project. In 2015, the company completed a two-year cleanup that turned five acres of industrial waterfront into a wetland habitat with native plants and woody debris. The company touts on its website an award from NOAA for the project.

Boeing recovered $51 million from the federal government in 2018, through a lawsuit that said the Duwamish pollution was the result of the company’s role as a defense contractor during World War II.

Originally, the Superfund was fed by a tax on a variety of polluting industries to ensure cleanups could proceed even if polluting companies went out of business or couldn’t afford to pay.

But since that tax expired, in 1995, taxpayers of all kinds have spent billions of dollars cleaning up hazardous waste released by private companies, according to a 2017 analysis by News21, an investigative journalism project connected to Arizona State University.

The Lower Duwamish River parties are scheduled to embark on the full-scale cleanup as soon as next year.

The schedule will be complex and intricate. In-water work, which will involve dredging and barging away contaminated sediment, can only happen during a short window, typically October to February, to avoid interfering with fish migration or fishing treaties. It will likely take years to complete the cleanup.

Removal of contaminants from the river’s most polluted stretch, where Boeing Field airport is located, is supposed to come first, after a final bout of planning and contracting, according to the EPA.

But it isn’t clear how the lengthy cost negotiation will play a role in the timeline. The dozens of parties responsible for the cleanup have to agree to a payment plan and present it to the EPA for approval.

Agreeing is key to avoiding years of litigation and bickering.

The city of Seattle warned as much on its website, where it notes that cleanup parties can disagree, “but everyone knows that those who reject their assigned shares are likely to be sued by the others.”