The company said Friday it would end production of its Everett-built 767 freighter in 2027, after it completed current orders for 29 jets. It also delayed the rollout of another plane built in Everett, its new 777X, to 2026, following years of certification delays and the recent discovery of a defective part that grounded test flights earlier this year.

The job cuts will affect roughly 17,000 workers across all levels of the company, Boeing said Friday. It’s not clear how the cuts will impact the company’s 66,000-person Washington workforce, or the striking Machinists. In a note to employees Friday, new Boeing CEO Kelly Ortberg told workers the company had to “reset our workforce levels to align with our financial reality.”

“We need to be clear-eyed about the work we face and realistic about the time it will take to achieve key milestones on the path to recovery,” Ortberg continued.

“We also need to focus our resources on performing and innovating in the areas that are core to who we are, rather than spreading ourselves across too many efforts that can often result in underperformance and underinvestment,” he said.

After a year of slow production following a panel blowout in January, Boeing was already in a weakened financial position when more than 33,000 machinists walked off the job Sept. 13.

Now, as the strike enters its fifth week, each party has accused the other of refusing to negotiate in good faith and the two remain deeply split on the terms of a new contract, particularly around wage increases and retirement benefits. Talks broke down this week after two days at the bargaining table, leading Boeing to withdraw its most recent offer.

On Friday, Boeing said it expected to lose $1.3 billion in operating cash flow during the third quarter this year, according to financial results released before its scheduled earnings call later this month. It expected third quarter revenue of $17.8 billion, and a loss of $9.97 per share.

Picketing outside Boeing’s Everett factory Friday, Jeremy Niethamer, a 12-year Boeing veteran, remained steadfast in holding the line even in the face of looming layoffs.

“What we’re asking for is not going to cripple the company,” he said. “We’re not asking for too much … and I think that’s why the community is behind us.”

Uncertainty around layoffs

Shortly after the Machinists walked out in September, Boeing initiated one-week furloughs for nonunion employees to preserve money as its factories sat idle. On Friday, Boeing said it would end the cycle of furloughs and reduce its workforce by 10% over the coming months.

“We know these decisions will cause difficulty for you, your families and our team, and I sincerely wish we could avoid taking them,” Ortberg wrote to employees Friday. “However, the state of our business and our future recovery require tough actions.”

The layoffs will affect all functions across Boeing’s 170,000-person workforce, from executives to managers to front-line employees.

Boeing leadership will share detailed information with workers next week, Ortberg said.

On Friday, the Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace, the union that represents white-collar engineering workers at Boeing, said it asked the company for more details regarding the layoffs.

“Rather than resolve the IAM strike and focus the company’s resources on rebuilding the trust of regulators and customers, Boeing leadership has decided to harm every aspect of the company,” SPEEA Executive Director Ray Goforth said in a prepared statement. “This doesn’t inspire confidence that there’s an actual plan to save Boeing from its self-inflicted wounds.”

On the picket line Friday, workers were shocked to hear about the job cuts — but divided on what it meant for the future of their jobs and their strike.

Emmanuel Lawrence, who has worked at Boeing for five years, said he was concerned about his own job security and “the longevity of the company.” But Michael Swale, who has been at the company for 1½ years, said Boeing couldn’t afford to lose the Machinists.

“When this is resolved, after Boeing offers us a fair deal and we get back to work, we are going to be slammed,” Swale said. “Of course I’m worried about my job, everyone is. But it feels like Boeing is doing this because they’re panicking.”

More on Boeing and the Machinists strike

- Boeing to cut 10% of workforce, stop most 767 production amid strike

- Push to end Machinists strike stalls as storm clouds gather over Boeing

- Boeing withdraws contract offer

- Boeing to furlough tens of thousands of workers as Machinists strike bites

- Furloughed in WA? Here’s what you need to know

- How long Boeing Machinists’ strike could last and how it impacts WA

- Read the latest stories on Boeing

In Snohomish County, where Boeing is the top employer, the proposed layoffs will have significant repercussions, local leaders predicted Friday.

“Boeing’s workforce is deeply integrated into many sectors, from aerospace suppliers to local service businesses, amplifying the ripple effects of any reductions,” Economic Alliance Snohomish County President and CEO Wendy Poischbeg said by email.

A survey of local aerospace suppliers found “both strong support for Boeing employees and growing concern about the future,” Poischbeg added.

U.S. Rep. Adam Smith, a Bellevue Democrat whose district includes Boeing’s Renton factory, said he was “disappointed” in Boeing’s decision to lay off workers.

“Boeing’s success relies on its dedicated employees, and investing in them is crucial for long-term recovery,” Smith wrote in a social media post. “Now more than ever, a fair resolution to the machinist’s strike is essential to restore trust.”

Before Friday’s announcement, analysts from S&P Global estimated the strike would cost Boeing more than $1 billion per month.

The end of the 767

In its early financial results released Friday, Boeing said it expected to report $5 billion in losses for the third quarter this year. It expected it lost $3 billion on the 777X and 767 programs in its commercial division.

It pushed the first delivery of the 777-9 to 2026 and the 777-8 freighter to 2028, resulting in a $2.6 billion loss.

The defense, space and security division reported $5.5 billion in revenue and $2 billion in losses.

In his letter to employees, Ortberg said Boeing’s defense and space division, which includes its Starliner spacecraft, was “simply not where it needs to be.”

Boeing expects “substantial new losses” in its defense division this quarter, driven by the strike, “continued program challenges” and the decision to end production on the 767 freighter. The 767 and 737 airframes are used in Boeing warplanes, and Boeing ending the commercial version of the 767 will increase the cost of its military derivative.

Boeing had originally planned to shutter that 767 program in 2028, but a provision in the newly passed Federal Aviation Administration reauthorization bill would have allowed it to continue selling the plane until 2033.

FedEx and UPS are the only customers for the 767 commercial freighter. With a range of 3,255 nautical miles and the ability to haul up to 52 tons of cargo, the freighter variant took off in the mid-1990s to expand Boeing’s share of the cargo market.

In Everett, Boeing will continue producing the KC-46 military tanker and the 777.

In a statement Friday, the Machinists union said the strike could not have impacted Boeing’s long-term plans for the 767 program. It called the company’s announcement “dubious, at best” and said it was “troubling” in light of the current tensions around labor negotiations.

“The path to resolve this strike begins at the bargaining table,” the Machinists union said. “An unwillingness to stay at the table only prolongs the strike. CEO Ortberg has an opportunity to do things differently.”

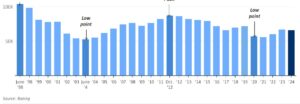

A year of turmoil

Boeing has faced financial pressure and heightened regulatory scrutiny nearly all year after a panel blew off a Renton-built 737 MAX plane midflight in January. The company has slowed production at its factories since then to focus on safety and quality, and continues to face increased oversight from regulatory agencies.

On the same day it announced cuts to its workforce and changes to long-term production, a government watchdog accused the Federal Aviation Administration of failing to fix oversight of Boeing, letting defects and noncompliances in its planes slip through the cracks.

Boeing was also in court Friday for a hearing on a plea deal it agreed to earlier this summer to resolve criminal fraud charges following two fatal 737 MAX crashes in 2018 and 2019. In that hearing, those who lost loved ones in the crash asked for more criminal accountability for Boeing and its executives for their role in the accidents.

Ortberg said Friday that Boeing remains focused on safety, quality and delivering to customers.

“We will navigate through this moment,” he said. “We will re-focus our company, and we will restore trust with all those who depend on us.”