By

The gleaming new International Arrivals Facility at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, which opened last year at a cost of about $1 billion, was supposed to fit 20 big, widebody aircraft simultaneously.

But according to the Port of Seattle, that many long-haul aircraft won’t fit side by side because of flaws in the design.

The Port, which operates the airport, says the facility can currently take only 16 large aircraft at a time.

In a letter sent in August to Clark Construction, which built the new facility, the Port said the 20% shortfall in capacity could cause “damages to the Port’s operations in the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars over the expected life of this project.”

The letter states this leaves Sea-Tac “with an international-flight capacity problem that this project was originally intended to solve.”

The Port is redesigning the layout of various gates to allow some bigger planes to fit and to try to resolve the capacity issues. It estimates the reconfiguration will cost an additional $78 million.

“The Port is actively and aggressively working to address deficiencies,” Sea-Tac Airport spokesperson Perry Cooper said in a statement. “Plans have not been finalized.”

In the meantime, while fewer long-haul planes can arrive, lawsuits are flying.

In December, Clark sued the Port for more than $60 million plus legal costs, alleging it wasn’t paid for extra work done due to design changes and enlargement of the scope of the project, as well as extra costs from the pandemic.

In January, the Port countersued Clark for more than $100 million in damages, including the bill for the gate reconfiguration and other rework.

The Port blames the design shortfalls on Clark, which it claims is liable for the cost of fixing the problems.

Both the Port and Clark declined interviews, citing the pending litigation.

The details of the dispute are revealed in the legal documents and in correspondence between the two parties from summer 2021 to last November, obtained from the Port via a Public Records Act request.

The project

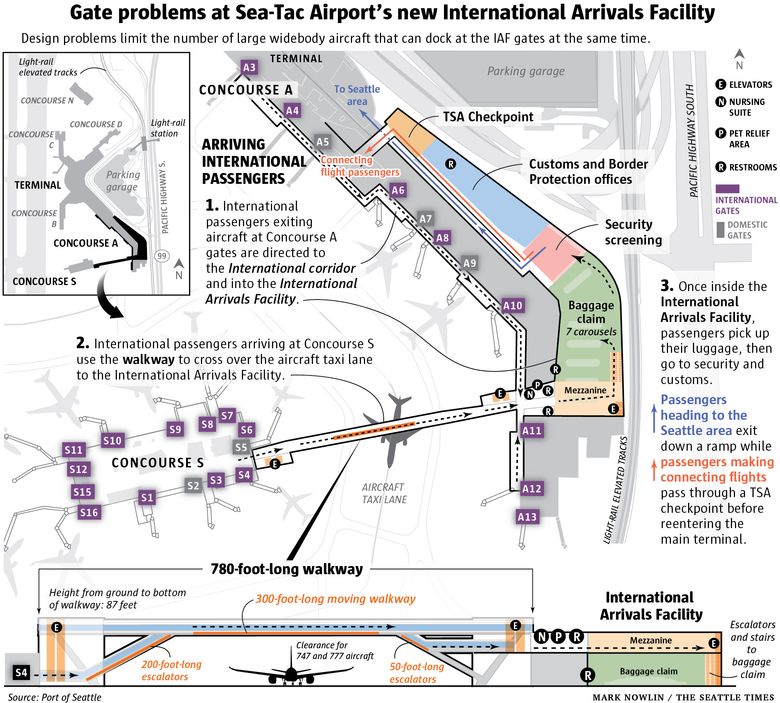

The International Arrivals Facility project entailed designing and building a 450,000-square-foot addition to the current Concourse A in the main terminal connected to the South Satellite terminal via a walkway.

Secure corridors had to be established to separate domestic passengers from international passengers, who must pass through customs.

Sign up for Evening Brief

Delivered weeknights, this email newsletter gives you a quick recap of the day’s top stories and need-to-know news, as well as intriguing photos and topics to spark conversation as you wind down from your day.

The original 2014 budget was $344 million. But the Port expanded the scale of the facility over time and the pandemic added further costs, so that on opening the budget had ballooned to $968 million.

That’s not in taxpayer dollars. The project is funded by airport revenue that flows from airline ticket fees and other airline service charges, as well as retail tenants at the airport, rental car facilities, parking charges, and taxi and shuttle fees.

Construction extended four years beyond the initially planned completion date in 2018. The facility finally opened to great fanfare last year.

International passengers who disembark at Sea-Tac’s South Satellite now enter the main terminal via the 780-foot-long aerial bridge with a moving walkway and a stunning view as jets taxi underneath.

They spill into a majestic arrivals hall where, along with passengers who have arrived at various A gates also designated for international travelers, they collect their checked baggage and go through customs.

It’s a grand interior space for a traveler’s first impression of Seattle, a big improvement on the previous international arrivals setup in the windowless bowels of the South Satellite.

Clark Construction, headquartered in Bethesda, Md., with 4,200 employees, was the lead contractor for the project, which was designed by architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

Clark built the much-praised new Kansas City International Airport terminal that opened in February. And it is almost finished building the striking new addition to the Convention Center in downtown Seattle.

The design of the gate area where jets arrive and park and where passengers board or disembark was subcontracted to Arup, a London-based design and engineering firm responsible for landmark building projects all over the globe, including the Sydney Opera House.

It’s this exterior gate area that’s now at the center of the dispute.

Gates where some jets won’t fit

In an emailed statement, Clark Division President Brett Earnest, who leads projects in the Pacific Northwest, said the company engaged “best-in-class aviation design experts” to work on the International Arrivals Facility and that the completed facility “meets the Port’s established goals and requirements.”

“The current gate configuration is consistent with the Port-approved concourse study and meets the specifications and requirements per our contract,” Earnest added.

The Port disagrees.

Each international gate had to be designed to take specific widebody aircraft. For example, Gate S5 at the South Satellite was to accommodate Airbus A330s and Boeing 787s. Gate S4 was to take the larger Boeing 777.

There had to be room to safely maneuver not only the aircraft but all the service equipment that surround the parked planes — fuel hydrant trucks, potable water and lavatory trucks, baggage carts and push-back tugs — as well as the passenger loading bridge that is rolled over to the jet’s door.

After conducting “aircraft fit checks,” the Port concluded that at some gates the required jets could not fit in the allotted space.

In the August letter to Clark, the Port stated that “Gate Fit checks have identified issues at Gates A6, A8, S6 and now S4, where these gates cannot accommodate the design aircraft specified in the 100% design and in fact cannot accommodate a Widebody Aircraft.”

After failing to get Clark’s agreement to collaborate on a solution, the Port in fall 2021 undertook an independent analysis of how to fix the issues.

One workaround by the Port showed a 777 widebody jet could dock at Gate A6 by swinging the jet in an arc and parking slantwise to the building rather than pulling in straight to the gate.

But this arc meant the wings swept through the space at Gate A5 and so this could only be done if no aircraft was parked at A5.

The Port came up with proposals, outlined in a November letter to Clark, that entail not only restriping the lines on the tarmac that pilots use as a guide when docking their planes, but also major rework to the aircraft service equipment and buildings.

Pilots use guidelines like these when parking at airport gates. These lines lead to the South Satellite terminal. (Ellen M. Banner / The Seattle Times)

To allow a 777 to use gate A8, the Port proposes to move the stand at gate A9 where the passenger loading bridge is located approximately 55 feet toward gate A10. That’s estimated to cost $7.5 million.

To allow a 777 to use gate A6, it is evaluating if it could shift one of the secure passenger corridor entrances approximately 100 feet south, at an estimated cost in excess of $60 million.

Alternatively, the Port is calculating “the diminished value for losing the gate A6 widebody capacity for the 50-year life of the facility.”

And to allow A330s or 787s to use Gate S5, the Port is studying if it can relocate escalators and elevators that take passengers up to the walkway. The costs of this “are likely to be measured in the tens of millions,” the Port told Clark.

That November letter ends with the Port asserting that “Clark has refused to engage with the Port to identify solutions.”

“Accordingly, the Port … intends to continue to develop these options and recover all associated costs from Clark,” the letter states.

Earnest, the Clark division president, said in his emailed statement that these changes aren’t part of the company’s responsibility.

“The Port is now identifying modifications to gate design based on operational considerations that were not contemplated in the program requirements in our contract,” Earnest wrote.

Clark’s latest legal brief, filed in late February, asserts that the contract documents defining the work “specifically state that Clark was to design the Project to accommodate narrowbody aircraft at Gates A6 and A8, not widebody aircraft.”

In addition, “Clark denies that the Port attempted to work with Clark to find solutions to the alleged gate configuration issues,” the legal brief states.

A trial at King County Superior Court is scheduled for December.

Whichever party is found liable for the flawed design of the gates, the capacity shortfall is a serious blow to the airport and any fixes will clearly be expensive.

Dominic Gates: 206-464-2963 or dgates@seattletimes.com; on Twitter: @dominicgates.