When the Spanish flu was pronounced over back in 1918, Seattleites famously torched their masks before rushing into the streets to celebrate.

Better hang onto those spare boxes of N95s this time around. Not for future virus pandemics, necessarily. For another respiratory ritual around here: smoke season.

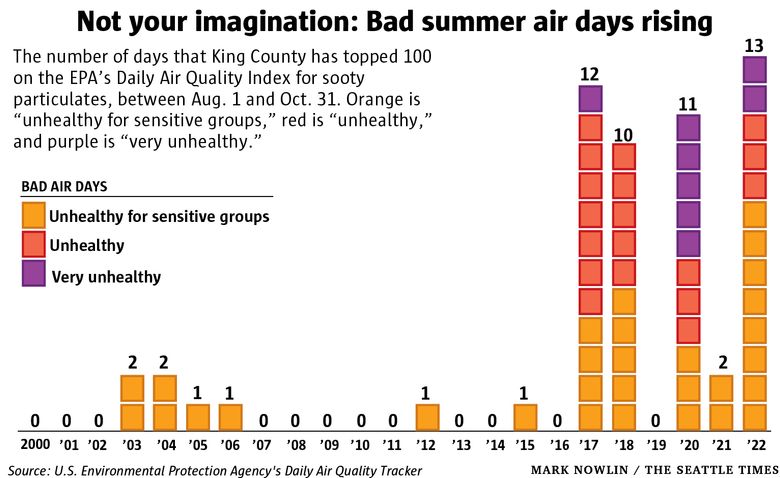

It certainly feels like wildfire smoke now visits Seattle like an annual plague. But sometimes memory doesn’t match the facts and data, so I decided to chart the number of “bad air” days recorded at air quality stations in King County, between Aug. 1 and Oct. 31, going back as many years as the data would carry me.

It’s not your imagination. The cloaking smoke of the past few weeks has become a new normal, one with an apocalyptic feel. The EPA long ago classified wildfire smoke as an “exceptional event,” but that is clearly no longer the case.

Almost all the summer and fall “bad air” days since monitoring began were in the past six years. Starting in the fire season of 2017, King County has suffered six times more bad air days — 48 — than there were in all the late summertime periods prior to that back to the year 2000.

Bad air caused by sooty particulates used to be a wintertime thing, due to wood-burning stoves. From 2000 to 2016, it just wasn’t an issue in summer or fall. Eleven of those years had zero bad air days during late summer, and the others had only one or two. A “bad air” day is defined as an air quality index daily average reading of more than 100 micrograms per cubic meter of air.

The EPA data set only went back to 2000. The local air monitoring group, the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency, said the recent late-summer smoke events are unique to the beginning of testing more than 40 years ago. The badness of our bad air days has also spiked, as they’re worse now than anything ever recorded in wintertime.

“Since 2015, we have faced unprecedented wildfire smoke — the highest fine particle levels since we started monitoring for them in 1980,” the agency said in its 2021 report.

The 2022 smoke season was not as severe as 2020. It went on the longest for Seattle on record, though, with 13 bad air days sprinkled over more than a month.

All of this was predicted by climate researchers — that rising temperatures would lead to more Western fires that burn longer and with greater intensity. It’s startling how quickly it’s become a part of life, altering the rhythms of summer itself. The outdoor recreation industry has recalibrated around it, as have festivals for music and Shakespeare. (New York Times headline in August: How Summer Stages are Threatened by Climate Change.)

This data is for King County air stations only; the smoke effects in the interior West have been much worse. This shows though that even for a temperate city like Seattle, located on the ocean, smoke season is becoming routine.

I’ve heard some commentators suggest that there’s always been smoke in Seattle from big wildfires; the data indicates otherwise, at least since 1980. Others say the smoke events have more proximate causes, such as forest managers refusing to douse the fires. But what Seattle’s smoke profile demonstrates is how vast and out of our direct control the problem has become.

The 2017 and 2018 smoke events were due mostly to smoke drifting down from huge British Columbia forest fires. The 2020 smoke season conversely came from the south — from epic fires that scorched California and more than a million acres of Oregon. The result was that a “super-massive plume” as large as Oregon itself collected over the ocean, coming back ashore in September 2020, to blanket Western Washington in what state air quality officials dubbed a “smoke storm.”

This year’s event was disturbing in a different way. It was due to fires that spread, atypically, on the wetter west side of the Cascade Mountains.

We’ve been getting smoked from all sides — from Canada and Alaska, from the south, and of course from fires in the interior and now even the west side of our own state. If it’s seemed at times like the whole West has been on fire, it essentially has: The only three years with more than 10 million acres burned have all been since 2015.

Seattle’s smokeouts can’t all be blamed on climate change; forest and firefighting practices play a role, and fires have raged for millennia. But scientists say it jacks up the odds.

“It’s not going to be every summer, by any means, but this is the sort of thing that’s going to be happening more,” said state climatologist Nick Bond.

Contemplating doing something to quell it is like a microcosm of the larger global warming issue. It’s complex and multinational in scope. Yet while you can literally taste it in the air, parts of our idiocracy, I mean our political system, won’t acknowledge it as real (see America’s pandemic meltdown for a similar example).

I’m not a total climate doomist, but I have come to think answers are more likely to be found in scientific discovery, not politics or culture. That’s why it was such a breakthrough last summer when the Democrats’ big climate bill in Congress shifted to focus almost entirely on incentives for clean energy tech and research, rather than taxes or other “eat your broccoli” attempts to alter human behavior. You go with what has a shot of working.

The smoke is now gone, this year’s season hopefully past. The air quality data suggests that we have indeed become canaries, who now live most every summer or fall, for a couple of weeks, in a coal mine.

Like I said up top, hang onto those N95s. It turns out the whole pandemic routine of masking and staying home might have just been practice for a condition more permanent.