Washington state’s new Highway 99 tunnel lost so much traffic because of work-from-home that toll increases and a bailout by the Legislature are needed to solve a permanent budget shortfall, the state Treasurer’s Office predicts.

Planners couldn’t have foreseen that the COVID-19 pandemic would slash toll revenues, which are to cover $200 million in construction debt plus operating costs for the $3.3 billion project that includes the tunnel and connecting roads.

But in trying to boost revenue, the state’s hands will be tied by its own construction of a giant Alaskan Way surface street, which will give drivers more leeway to pass downtown Seattle without paying tolls.

Already, the tunnel is $29 million in the red, despite an urgent 15% toll-rate increase to catch up last year. Tolls range from $1.20 to $2.70 each direction for Good to Go passholders, varying by time of day.

Jason Richter, deputy state treasurer, warned the state Transportation Commission to expect reduced demand because telework will continue for decades.

“We’re seeing a permanent reduction in revenues that ranges from 16% to over 30%,” he said. Without a traffic resurgence or new money, losses would accumulate to $237 million by 2051, a spring 2022 forecast says.

Such bleak forecasts illustrate the changing nature of work and travel, especially in Seattle, where central-city commutes have dwindled since pandemic lockdowns began in March 2020. Office towers, conventions, tourism and performing arts have reopened, yet tunnel use lags other highways across the U.S.

Robert Poole, a toll roads expert at the Reason Foundation, called the Seattle numbers sobering. “This is not a common problem that’s affecting other metro areas in the country,” he said.

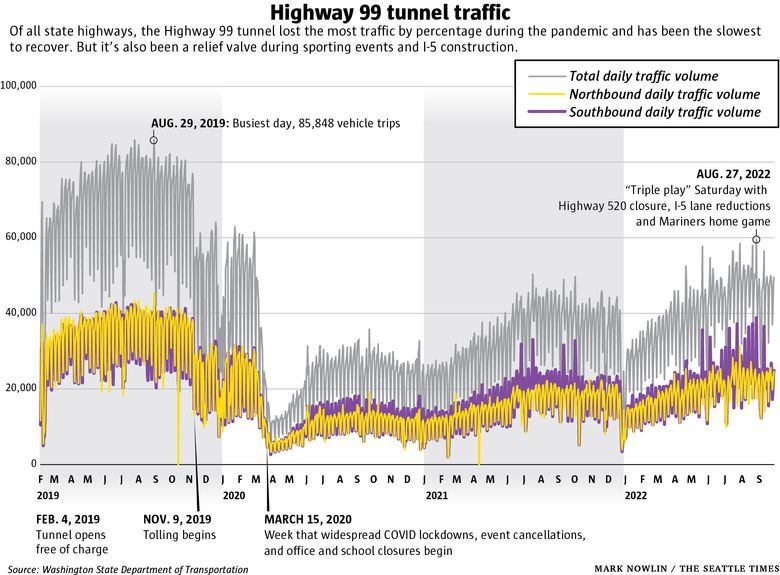

But just in the last few weeks, trips surged to an average 43,845 trips a day in September, a gain of 5,000 since spring and similar to just before the pandemic, based on a Seattle Times review of state data. The tunnel provided a relief valve for stadium events, and to escape Interstate 5 congestion during weekend road repairs.

“I think it’s successful. It had impacts from the pandemic, just like some of the other toll facilities did. But toll traffic and toll revenue is coming back, and slowly but surely,” said Ed Barry, toll division director for the Washington State Department of Transportation.

By comparison, the Highway 99 project’s target volumes, to be fiscally sustainable with minor diversion, were 53,000 daily tunnel trips in 2020, rising to 67,400 by 2040.

Highway 520 also lost traffic since 2020, while the Interstate 405 express toll lanes are filling again this fall, sometimes triggering the $10 maximum rate.

For the state to encourage traffic creates another set of problems, in this age of global warming and road casualties. But if drivers do return, it’s better they cruise the tunnel than clog downtown streets.

A financial crisis?

When the tunnel opened Feb. 4, 2019, the state missed out on $10 million by giving drivers a nine-month grace period with free trips, to encourage tunnel use. Another $19 million in “loans” from other WSDOT funds were allocated in 2021-22 to cover pandemic toll losses, a treasurer’s spreadsheet shows.

Lawmakers imposed a new burden at the last minute, that tolls generate millions per year into a long-term repair fund.

Soon after opening, the toll-free tunnel attracted 75,000 trips on weekdays, nearly the same as 80,000 who bypassed downtown in the old Alaskan Way Viaduct. (Or 109,000 if you include drivers using the viaduct’s now-defunct downtown exits.)

Suddenly, when tolls began, WSDOT lost 20,000 daily trips, dropping to 55,000 per weekday. Of those lost trips, about 10,000 shifted to I-5, city streets and transit, state monitoring found, while the rest were unaccounted for, perhaps including telework, bicycling, side streets or canceled personal drives.

Volumes sank further when the pandemic struck, to an average 25,655, including weekends, for 2020, and generated $14 million, half the target. This year’s projection is $22.9 million, still short of the $35.4 million benchmark.

“I think it’s going to be a budget problem. Who’s going to pay for it?” said longtime House Transportation Committee member Ed Orcutt, R-Kalama. “We were told the tolling is going to take care of a certain amount, and now it’s not.”

Orcutt said the funding gap makes him leery of the future I-5 Interstate Bridge Replacement to Portland near his district, where tolls are part of a $4.8 billion funding concept. “It’s really leaving me with a question, about how reliable the projections are on that bridge.”

WSDOT did not sell tunnel-financing bonds that rely on tolls, but mixed Highway 99 debt with other roads statewide, funded by gasoline taxes. Therefore, there’s no default, bankruptcy or loss of credit rating if the tunnel loses money.

“It gives us a little more wiggle room with lawmakers,” said Reema Griffith, transportation commission executive director.

That differs from Highway 520, where toll income is pledged under contract to repay up to $1.2 billion in bond debt to investors.

The Legislature has been pliable, voting this year for a $130 million subsidy that lowered Tacoma Narrows Bridge tolls from $5.25 to $4.50 round-trip, in addition to $111 million previously transferred.

House Transportation Committee Chair Jake Fey, D-Tacoma, says all future state and federal money is earmarked for projects, so cash for Highway 99 must be taken from other road needs.

“Some of this just needs to play out a bit,” Fey said. “We don’t know what the new normal is yet.”

WSDOT announced Thursday it will receive $77 million from tunnel contractors for cost overruns, after the state Supreme Court declined to hear arguments over a 2019 jury ruling in WSDOT’s favor — a money source that Fey and ranking Senate Transportation Committee member Curtis King, R-Yakima, said lawmakers could apply to fill gaps in Highway 99 toll revenue.

Tolls used to rouse emotions and rivalry, from politicians elsewhere who resented subsidizing Seattle’s glitzy waterfront redevelopment.

In 2009 the Legislature voted for tolls to recover $400 million of a $2.8 billion state contribution to build the tunnel plus connecting roads — assuming $400 million was the extra cost for a tunnel instead of another viaduct. They lowered the goal to $200 million in 2013, when a planning committee realized a projected $3 toll would provoke drivers to skip the tunnel and clog other roads.

Now that’s becoming elusive, too.

“The proponents constantly overstate toll revenue and constantly underestimate the amount of people that will avoid tolls,” said former Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn, who opposed the tunnel. He considers tunnel toll shortages an instance of “strategic misrepresentation” that occurs worldwide, by project sponsors.

Who’s using the tunnel?

WSDOT hasn’t done surveys, but data shows tunnel driving fluctuates by season. September’s surge doesn’t guarantee a lucrative January. Saturdays are busier than Sundays, Mondays and holidays in 2022. Southbound is busier than northbound, a trend for which the Mariners’ playoff race deserves some credit, Barry said.

During weekend I-5 repairs southbound in Sodo, an average 47,068 drivers used the tunnel, far more than on average weekdays. The busiest since the pandemic was Saturday, Aug. 27, 2022, when I-5 lane closures, a full Highway 520 closure and a Mariners game all happened.

Commute peaks have become less crowded than in the 2010s, as travelers spread more to midday and weekends. That could mean adjusting the toll rates (which jump from $1.50 to $2.70 at 3 p.m. weekdays) to be more even, Griffith said.

Is traffic coming back?

The Sept. 18 reopening of the West Seattle Bridge, which provides a direct Highway 99 northbound exit, has caused a “significant spike in volumes northbound,” said toll division spokesperson Emily Glad.

During the bridge’s 2½-year repair closure, a typical detour of 30 to 60 minutes deterred trips toward downtown and north Seattle.

“It’s incredibly convenient for me when I drive from West Seattle to the South Lake Union area” in just four minutes of highway travel, said Tom Rasmussen, former chair of the City Council’s transportation committee. The tunnel looks busier but still uncongested, he said.

Office occupancy is just 36% of pre-pandemic levels and hasn’t gained in recent weeks. King County Metro Transit serves only half its former 400,000 daily trips countywide. Sound Transit’s downtown hub at Westlake Station served only 9,600 average weekday trips in August, fewer than Northgate Station.

Since early 2020, an easing of emergency health regulations, along with more delivery vehicles, midday errands by teleworkers, and leisure trips have returned traffic back to pre-pandemic totals across the U.S. and Washington state.

Poole expects the national work-from-home average should land between 10% and 15% permanently.

For another six years or so, major deck reconstruction on I-5, from downtown to Northgate, will cause multilane, multiweek shutdowns on the Ship Canal Bridge, sure to push travelers into the tolled tunnel and help the bottom line.

Is WSDOT sabotaging itself?

Highway studies in the ’00s assumed ever-increasing traffic, and that half the drivers to Ballard and Magnolia would use the toll tunnel, and half would take surface routes.

It’s quite a tightrope walk WSDOT has undertaken, two decades after the 2001 Nisqually Quake damaged the viaduct.

“You can only raise the tolls so high, because there are a lot of free options,” Griffith said.

The Seattle City Council preferred a tunnel largely to avoid the risk that a surface highway would carry 45,000 to 75,000 cars, far beyond the 25,000 mark that architects called the limit for a pleasant, walkable waterfront.

But transportation agencies wound up delivering both a tunnel and a surface Alaskan Way four to six lanes wide, expanding to nine lanes plus parking near the ferry terminal. The widest blocks provide bus lanes, four general lanes, drop-off space and two left-turn lanes at the ferry terminal. It’s so vast, people push a pedestrian-signal button in the median, when they can’t cross from Pioneer Square in a single green light.

“The tunnel was and remains a betrayal of vision for a community that cares so much about climate and equity and sustainability,” said McGinn, now executive director of nonprofit advocacy group America Walks. “And so is the waterfront highway, for that matter.”

However, the Waterfront Seattle plan does add a landscaped overpass park, a pedestrian street near the stadiums, a small beach, broader sidewalks, street trees and bike lanes. The place is quieter with the viaduct gone.

Even now, McGinn said, the city should reduce Alaskan Way to three lanes between the Seattle Aquarium and the Olympic Sculpture Park, where there’s excess capacity and the coming four-lane Belltown bridge.

Drivers have adapted to a five-lane waterfront street since the 2010s, for a decade of roadwork and tolls.

It’s a thing

When the tunnel opened, WSDOT ran a $4.4 million marketing campaign that depicted the tunnel shape like Amazon’s trademark smile, and the slogan “It’s a thing” emphasized the tunnel is the fastest path through downtown.

Poole compares Highway 99’s role to the I-405 express toll lanes where drivers spend 75 cents to $10 to escape crowded general lanes.

“It’s parallel to I-5 and parallel to surface streets, which makes it an option people can take.”

Express toll lanes in other states that have to repay bonds have regained their traffic and even a profit, he said. Then again, traffic in Texas, Virginia and North Carolina didn’t lapse as long as in Seattle, he said.

“If they ask me for my advice, this is what they should do: Sell the benefits of a faster route through downtown and reliability of the trip time.”

Barry, the WSDOT toll director, said the tunnel already accomplished one goal. No longer is there any risk that the viaduct will topple in an earthquake.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled the last name of Ed Barry, WSDOT toll division director.