A review panel gave a new final estimated cost for the International Arrivals Facility of $968 million, up from the original $608 million. The project is also now eight months behind the original schedule.

The latest update on the budget-busting International Arrivals Facility at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport states that the new facility will open eight months later than originally planned and that its cost has swelled to almost $1 billion.

After a Port of Seattle staff report in April conceded big cost overruns and schedule delays, Port Commissioners appointed an independent review panel to assess the status of the project and make recommendations to get it finished. At that time, the budget had blown past the Port’s earliest 2013 estimate of $300 million and the original 2015 contract estimate of $608 million to reach $830 million, and the project was running five months late.

On Tuesday, the review panel report presented to Port Commissioners added another three months’ delay — a schedule it describes as “achievable but aggressive” — and gave a new final estimated cost that was $138 million higher again at just over $968 million.

In an interview, review panel chair John Okamoto said his team has determined this to be “a reasonable cost” given the “supercharged” construction costs in the region and a substantial increase over time in the scope of the project. He said further budget increases are not likely.

“There are reasons to have confidence that these projections are now good projections,” said Okamoto, who served at various points as human-resources director, engineering director and interim city council member for the city of Seattle.

He said the project last spring was in serious trouble because the relationship between the Port and the general contractor — Clark Construction, a major building and civil-engineering firm based in Bethesda, Md. — had “broken down” as each side blamed the other for cost overruns.

“There was unnecessary and unmerited finger-pointing,” Okamoto said. “Just like in a marriage, when things don’t go well, minor issues become major.”

He said both Clark and the Port removed the leadership on each side of the project “to reset the tone” and allow “a fresh start.”

Finishing the new facility to the new cost and schedule targets “requires both the Port and the contractor to work as one team, with a sense of urgency,” Okamoto added. “EverY day counts.”

Pressing demand

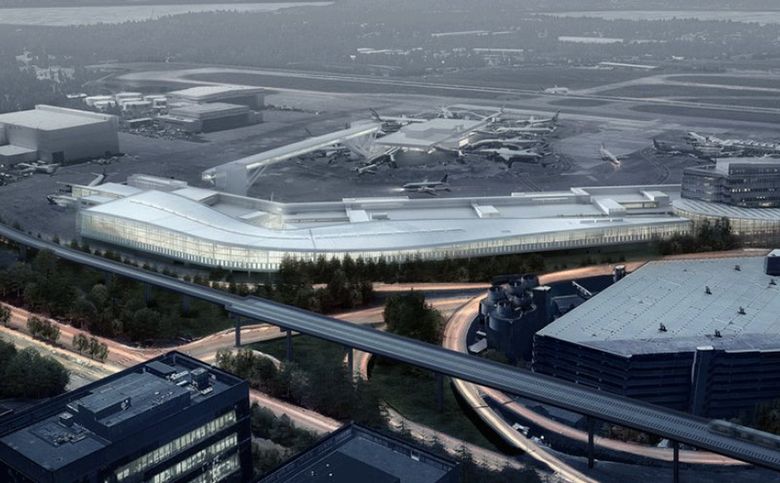

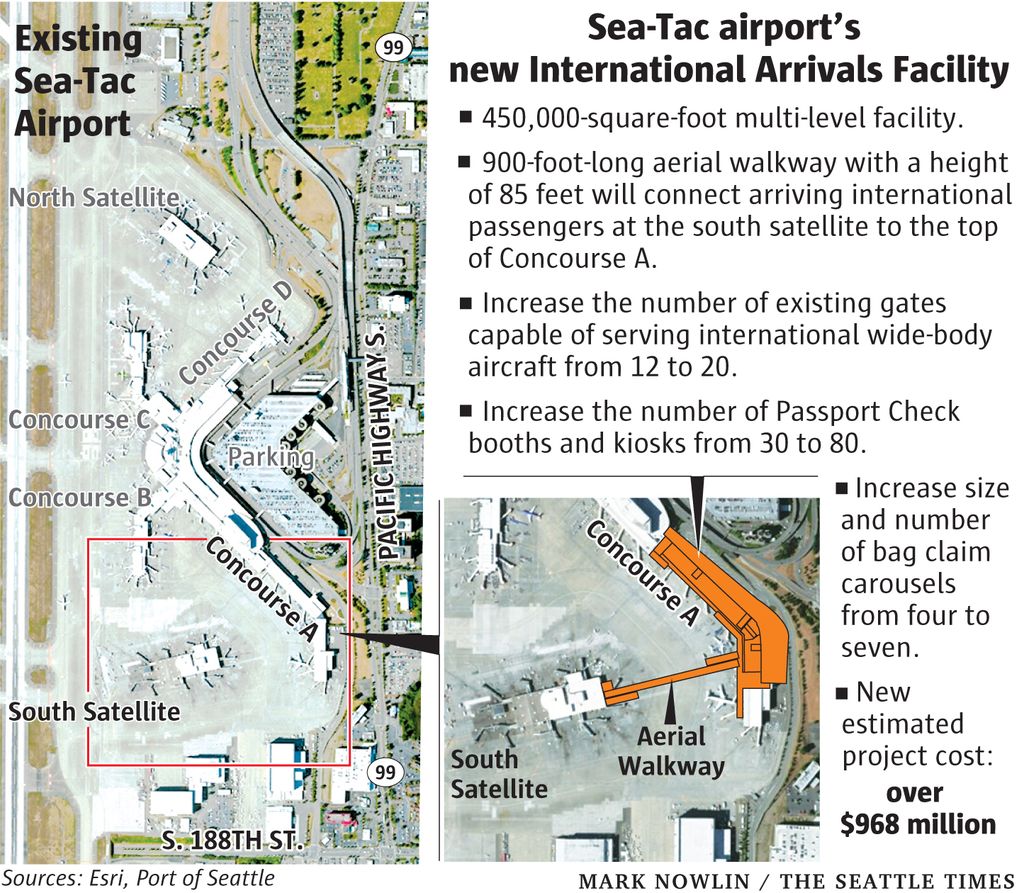

The new International Arrivals Facility (IAF) consists of a 450,000-square-foot grand hall that will wrap around the current Concourse A in the main terminal building and be connected to the south satellite by a 900-foot-long aerial walkway, a bridge that will take passengers 85 feet above the existing airplane taxiway.

The Port says it will double peak international-arrival capacity to 2,600 passengers per hour. That’s needed because the boom in international-passenger traffic, including nine new foreign airlines serving Sea-Tac in the past two years, makes the current south satellite facility woefully inadequate.

According to Port data, at peak hours every day, passengers arriving on 10- to 15-hour-long international flights are too often left sitting on the taxiways because no gates are available for their airplane to dock, or are forced to sit and wait on the aircraft when they arrive at a gate because the arrivals hall is too packed with people ahead of them, or, when they finally deboard, still face a long queue to reach customs and border patrol.

The new facility, with upgraded gates, a bigger interior space and a better technology system for customs, is supposed to fix all that, said Dave Soike, the Port’s chief operating officer, who has taken charge of the project’s management and oversight.

About 75 percent of the cost of the facility will come from federal fees that are tacked onto every passenger’s ticket at all U.S. airports — currently $4.50 per passenger for each leg of a flight up to a maximum of $18, plus an extra $6.15 for international passengers at Sea-Tac.

The remainder of the budget is covered by the Port using funds such as fees levied from the parking garage, airport concessions and taxis, Port spokesman Perry Cooper said.

Construction is now due to finish at the end of May 2020, and the facility is expected to open in August that year after extensive testing. In the 21 months remaining for construction, $485 million — half the estimated total cost — is still to be spent.

However, it’s only now — more than two and a half years into the project — that the budget and schedule are for the first time embedded in a fixed-price final contract, with penalties for delays and incentives to accelerate the work.

The panel negotiated with Clark a final “guaranteed maximum price” for the firm’s work of $774 million, with the rest of the $968 million cost consisting of sales taxes, port-management costs and a $23 million reserve fund.

Soike said that if Clark can’t complete the work within that budget, “They have nowhere to turn except their own bank account.” And Clark also faces fines of $10,000 per day if it’s responsible for any further delays.

Moving-target contract

In an interview, Port Commissioner Peter Steinbrueck said that the commission is setting up a system to track the project and to monitor costs and schedule every day.

“That has not been in place in the past up until now,” he said. “There’s a tremendous need to manage this very, very closely.”

Careful monitoring would have been advisable at an earlier stage. Both Soike and Steinbrueck said the contracting mechanism set up with Clark at the beginning of the project, a procurement methodology known as “Progressive Design and Build,” left lots of room for cost growth.

Realizing that the project would be very complex, with lots of linked parts that would have to mesh together and be constructed while the airport’s day-to-day operations continued without interruption, the decision was taken to award Clark a contract with the design, and therefore the price, not finalized, Soike said.

“We advanced some of the work to try to keep the project moving,” he said. “This contracting model allows the designers to get going early, to learn the scope (as they go) and add scope and start in the ground earlier.”

The design proved a moving target. Well into the project, the Port realized that it needed to add some extras: a baggage-conveying system, emergency generators and an automated system to help aircraft park at the gates.

Then the fire code demanded new requirements be included for fireproofing and smoke ventilation. Each of these changes pushed out the schedule and pushed up the cost.

“As we evolved the project, it was a different project than the original target budget,” Soike said. And Clark had underestimated even that original target, according to Port memos.

He said that the Port is now firm that it will add nothing more to the project, although it’s still possible that the federal government might add some further immigration or security requirements.

The increase in the work combined with the lack of oversight produced the Port’s belated realization last spring that the budget had ballooned — without knowing exactly the extent. That’s when the Commission appointed the review panel to find out how bad it was and to reset the project.

“Without this intervention, the project would still have been mired in a lot of challenges,” said panel chair Okamoto.

In a statement, Steve Dell’Orto, Clark Construction’s Western Region Executive Officer for the airport project, said the company has “committed our top leadership to ensure the successful delivery” of the arrivals facility.

“We have reached a Guaranteed Maximum Price and schedule for the IAF project, which we are confident we will meet,” he added.

Neither Clark nor the Port had previously used this project’s “progressive” contract model.

It’s not used for either of the two other large construction projects currently underway at the airport: the $700 million North Satellite Modernization, set to be completed in 2021; and the $320 million baggage-system upgrade that will go on through 2023.

Still, the review panel isn’t nixing the “Progressive Design and Build” model for the future.

Okamoto said no contracting model should be precluded, and instead the panel’s report emphasizes the need to make sure the Port has “the capacity and culture” on its staff to manage such a model more effectively.

Soike said the new project monitoring mechanisms now being put in place for the International Arrivals Facility will allow the Port to more efficiently review future cost overruns on all its active projects and provide “a better early-warning system.”

At the Port Commission meeting Tuesday, the commissioners emphasized the need for detailed progress reports and transparency as the project goes forward. They will vote on the new budget at the next meeting later in September.