Jeff Hickey’s three-decade stint in Seattle came to an end last March when the rent on his Queen Anne neighborhood home rose by $300 a month. He set his sights for a new place in SeaTac, where housing is cheaper and nearby green spaces are easily accessible.

Despite the constant noise of arriving and departing planes, which he says he’s gotten used to, Hickey is pleasantly surprised by South King County. It’s easy to drive to the Des Moines Creek Trail, and he likes the walkability of downtown Burien.

Hickey rents a room in his girlfriend’s home for $500 a month, compared to the $2,000 he would have paid for his 700-square-foot apartment in Seattle.

Although it was a coincidence that he moved at the start of the pandemic, “in retrospect it was a very good move,” Hickey said. He lost his job as a tech writer at Boeing last summer, and needed to save money, while some of the businesses he loved in Queen Anne closed — either temporarily or permanently. “The vibe there still has not recovered from the pandemic,” Hickey said.

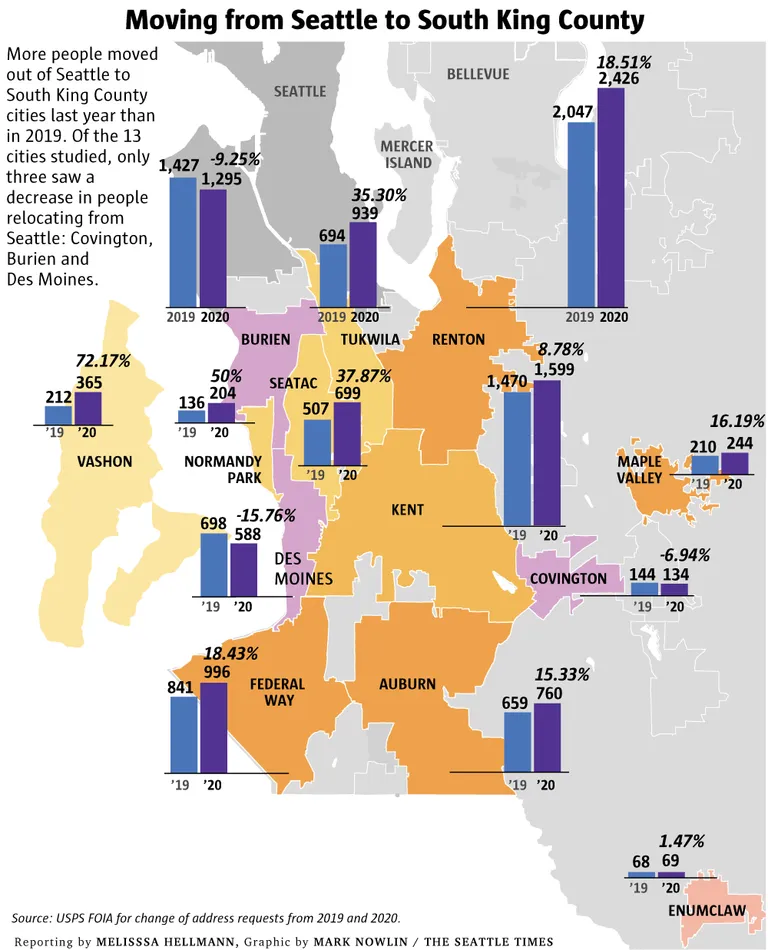

While Hickey and other Seattleites have moved to South King County for more room, affordability and access to green space for at least a decade, U.S. Postal Service data and anecdotal evidence suggest the trend may have increased during the coronavirus pandemic. A reader callout garnered dozens of responses from former Seattle residents who now call South King County home. According to change-of-address data collected by the postal system, in 10 out of 13 South King County cities, more people moved from Seattle in 2020 compared to the previous year.

Vashon Island, for example, tallied a 72% increase in former Seattle residents. In 2020, 365 people moved there from Seattle, compared to 212 in 2019. Normandy Park came in second with a 50% increase in former Seattle residents, with 204 transplants in 2020 compared to 136 in 2019. SeaTac had the third largest migration from Seattle at around 38%, with 699 in 2020 and 507 in 2019.

Out of the 13 cities studied, Covington, Burien and Des Moines were the only South King County cities that saw a decrease in people relocating from Seattle. White Center was not included in the USPS data.

Reasons for moving from Seattle to South King County included the luxury of living anywhere as a remote worker, according to a Seattle Times Hearken survey of migration patterns during the pandemic. One respondent moved from West Seattle to Tukwila last year so she could afford to buy a house large enough for her family of three. Another recently moved from North Seattle to the South End so she could afford more space after adopting a dog.

Hector Rodriguez, who moved to Burien from the Capitol Hill neighborhood last March, cited crime and Seattle’s high cost of living. He sought more space and wanted to live with his partner after he started working remotely from his job at the University of Washington. It would have been difficult to juggle working and living in his old studio, so Rodriguez traded up for a one-bedroom loft space with ample parking and an attached garage in South King County.

His friends in Seattle’s art and music community were similarly searching for more space at an affordable price last spring, so they also moved south to nearby Renton, White Center and Seattle’s South End, he said.

In Burien, Rodriquez found a higher concentration of Mexican restaurants, which reminded him of his Texas upbringing. “I felt like I was back at home,” he said.

The migration out of Seattle during the pandemic is reflective of a several-year trend more than a mass exodus. A new report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland shows the number of residents who moved out of urban areas in Seattle last year was comparable to the previous three years. Yet, there were far fewer people who moved into Seattle during that time compared to previous years.

SeaTac Deputy Mayor Peter Kwon began to notice an increase in people moving to the area from Seattle a few years ago. Last year, he met some young people who moved to the city from West Seattle because of the bridge closure. It encouraged him to create a survey in a SeaTac community group on Facebook where he asked people how long they’d lived in the area. Of the 181 respondents, 25% lived in SeaTac for less than four years, while 36% lived there for less than eight years. The primary reason people gave for moving to SeaTac was affordability. Case in point: Seattle housing costs are 96.7% more expensive than SeaTac’s, according to Bestplaces.net.

Affordability pushed Kwon to SeaTac from Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood about a decade ago. After saving to buy a home for 10 years as a systems engineer, he continued to lose housing bids. “That’s when I realized that there’s no way that I could afford a house in Seattle,” Kwon said, laughing.

Overall, the influx of new people from Seattle has been positive, Kwon said. Many homes in the area are remodeled, following the purchase of distressed properties by investors and developers who fixed them up. The wave of young, tech-savvy homeowners has galvanized the community, resulting in the formation of Facebook and Nextdoor groups where neighbors connect, he said.

The draw for businesses

Businesses also are increasingly moving to South King County, according to the Seattle Southside Chamber of Commerce, which serves companies in SeaTac, Burien, Tukwila, Des Moines and Normandy Park.

Andrea Reay, president and CEO of the SeaTac-based group, noticed many Seattle-based businesses were requesting advice on relocating to South King County when she started her position in 2016. She started tracking the trend the following year.

In 2020, the chamber received 376 relocation requests, 82% of which were from Seattle-based businesses. In 2019, there were 402 requests, 74% of which came from Seattle. Their top three reasons: affordability, transportation and friendlier tax regulations.

An enduring trend

Still, the recent southern migration is not new: U.S. Census data shows the population in South King County cities has increased for at least a decade. Kent notched a 43% increase in population since 2010, with 132,320 residents in 2019. The Auburn population increased by about 16% over a nine-year period to more than 82,000 in 2019.

“There’s a little more elbow room and space in South King County, which I think during the pandemic is important for people’s mental and physical health,” said Kyle Moore, the government relations & communications manager for the SeaTac City Manager’s Office.

The migration of Seattle’s Black population also has contributed to the changing population tallies. Prior to the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968, Seattle’s Central District was one of the only neighborhoods where Black people could purchase homes due to racial deed restrictions. But largely due to displacement, the neighborhood’s Black population dwindled by 60% in 50 years.

At the First African Methodist Episcopal Church, members who were priced out of the city began moving to South King County in the 1990s and the trend accelerated in the 2000s, the Rev. Carey G. Anderson said. Now, nearly half of the Central District-based church’s congregants live in South King County, which encouraged the church to create a satellite worship center in Auburn, he said.

“People are talking to me personally about the hardship of their housing situation and the inability to provide for their children,” Anderson said. “They’re willing to go anywhere.”

Where do people go when they can no longer afford South King County? Renton resident Ethel Green is considering Texas, Georgia, or Virginia where she would be far away from family and does not know anyone.

Born and raised in the Central District neighborhood, Green moved to SeaTac over a decade ago when the area became unrecognizable due to gentrification and displacement. She later moved to Renton for the affordable rent, but she said that prices in the area have become comparable to Seattle.

“I can see it’s going to become overcrowded and if I’m priced out, I’ll have to move,” Green said.

Deputy Mayor Kwon believes it is important for SeaTac’s cost of living to remain affordable. One of the first actions that the city council took when he was elected five years ago was to repeal the utility tax to save renters and homeowners about $40 a month. Additionally, the local property tax levy has not increased in seven years.

“People don’t want to be priced out of their homes,” he said. “People do not want to be displaced from their neighborhoods.”

Seattle Times columnist Danny Westneat contributed to this report.