Business at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport has been booming, and so has its carbon pollution. Airport officials say they can eliminate the climate-wrecking emissions without limiting the airport’s rapidly growing business.

But whether the wonder of air travel can be divorced from the global harm it does — let alone any time soon — is far from clear.

The Burning Question:

Air travel is one of the world’s fastest growing threats to the global climate, on track to triple its carbon dioxide emissions in the next 30 years.

The Port of Seattle, which runs Sea-Tac, says it’s leading the aviation sector away from that ominous trend and toward a day when taking to the sky no longer means harming the sky.

It’s electrifying

Outside a gate at Sea-Tac’s Concourse C, a member of the ground crew has extended an oversized power cord to a Delta Air Lines jet and plugged it in, just below the cockpit. A large yellow tube of cooled air also connects the plane to the airport. Together, the two umbilicals let the pilot turn off the jet’s big engines while the plane is parked.

At another gate, a conveyor belt on wheels delivers luggage into the bowels of a Horizon Air commuter plane. The little tractor that hauls the luggage around runs on an electric motor.

Infrastructure installed by the airport, including 300 charging stations to date, made it possible for airlines to switch their ground vehicles off petroleum and onto electricity.

“We’ve got this installed now at the north half of the airport, working on the south half,” said Elizabeth Leavitt, who runs the airport’s environmental programs.

It will soon be the first U.S. airport to have the charging stations airportwide, according to Sea-Tac officials.

When it does, the airport will be “saving about a million gallons of gasoline every year that would’ve been powering this equipment and cutting our carbon emissions,” Leavitt said.

Other projects at the airport have comparable or greater fuel and carbon savings.

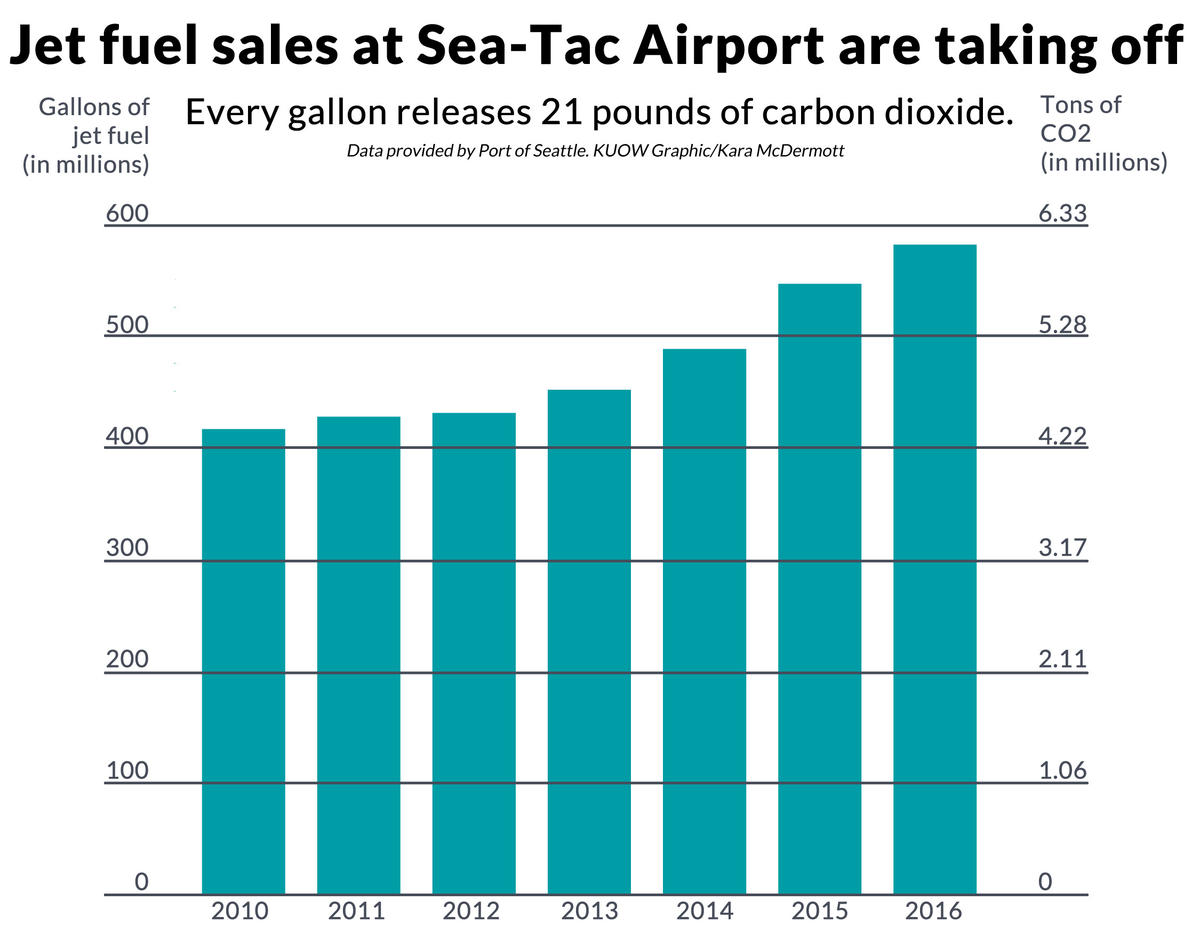

A few million gallons of fuel sounds like a lot of savings. But it’s a drop in the bucket compared to all the jet fuel that flows through Sea-Tac Airport.

Each year, jets fill up with around 600 million gallons of jet fuel at Sea-Tac. That’s enough to release 6 million tons of heat-trapping carbon dioxide, more than every resident and business of Seattle, according to the city’s latest greenhouse gas inventory.

And the surge in passengers means emissions are increasing despite the variety of energy-saving projects.

“The airport has actually been the fastest growing airport in North America for the last three years, and we’ve seen incredible growth,” Leavitt said. “We’ve had double digit growth for three years running.”

Over the next 20 years, the Port of Seattle is planning to double international flights at Sea-Tac and triple air cargo. That growth makes reducing emissions a steep climb, especially when possible solutions like biofuels or electric airplanes are a long way from being commercially viable.

The airport aims to get 10 percent of its fuel from locally produced biofuel a decade from now and 50 percent by 2050.

“I really think the Pacific Northwest is uniquely positioned to lead on sustainable aviation fuels,” Leavitt said. Washington State University, Boeing and Alaska Airlines have all participated in feasibility studies or pilot projects to try to get biofuel production going.

Currently, only one refinery in the nation makes bio-jet fuel. The Los Angeles-area refinery converts food waste to provide United Airlines with 0.16 percent (that’s one sixth of one percent) of its jet fuel.

I asked Leavitt if Sea-Tac can live up to its promises of climate leadership without reducing the demand for air travel.

“I don’t really know that that’s a Port question to answer,” Leavitt said. “We have to grow because of what the public demands of us, and that’s the role that the Washington state legislature has really given the Port of Seattle. That’s our job.”

Whether it’s biofuels or more energy-efficient planes, aviation watchdog Daniel Rutherford with the International Council for Clean Transportation in San Francisco said efforts to tame the climate impact of aviation are at a disadvantage.

“We do have this current headwind in that jet fuel is very inexpensive right now,” Rutherford said. Prices plummeted three years ago and have stayed fairly low since. “As long as fuel continues to be this cheap, we wouldn’t expect the manufacturers to be very ambitious on fuel efficiency,” he said.

The airline fleet is getting more efficient each year, but air travel is growing three times faster. On climate, aviation is still moving backwards.

Passengers keep coming

And as long as fuel remains cheap, the demand to fly will probably stay high, even among people who know how harmful it is.

I spoke with a couple of passengers on their way to the airport, both of whom happen to do environmental work.

“I went to school for environmental studies, so of course transportation was a big factor in greenhouse gas emissions,” Evan Bue of Seattle said on his way to catch a flight to Oakland.

“Since you’re well-educated on this, does the impact of flying affect how much you fly?” I asked.

“If I’m being honest, no,” Bue replied.

“Definitely the impact of my travel has crossed my mind, but I’m not an expert in what I can do specifically as an individual to reduce that,” Sarah Laycock of Seattle said on her way to visit family in Florida.

She works on energy efficiency for the state. I asked her if she ever avoided flying because of its impact.

“To be honest, I haven’t, but it’s not really an option for me not to visit my family,” Laycock said.

She said she was glad to learn that the airline she was taking to Florida, Alaska Airlines, is one of the most fuel-efficient for domestic flights. Flying on Alaska does about one-fourth less damage to the climate than flying on the dirtiest airline, Virgin America, according to a study from the International Council for Clean Transportation.

That group’s Daniel Rutherford said he does try to limit his air travel. “I’m often invited to a meeting or a conference, and the first question I ask myself is really, ‘do I have to go?'” he said. “And I try to find other options, including having someone local attend in my place or giving a remote presentation.”

Even with rapid growth, Sea-Tac officials say they can slash emissions in half by 2030 and eliminate them by 2050 by improving efficiency and using things like biofuel.

But there’s a catch.

Jet fuel is the airport’s dominant source of pollution. Yet the airport only tallies emissions from jet fuel burned on the ground or during takeoffs and landings. If a plane’s above 3,000 feet in the sky, Sea-Tac and other airports say the emissions are airlines’ responsibility, even if that fuel was pumped at an airport.

“Our aviation partners, the Boeings of the world and the airlines of the world, have their own strategies in place to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” Leavitt said.

U.S. airplanes put out seven times more carbon dioxide each year than planes from the world’s next largest polluter, China, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Special treatment

The United States doesn’t regulate carbon pollution from planes, unlike cars, trucks and power plants.

It is technologically harder to fly without burning fossil fuels than it is to drive.

“We know we can electrify cars quite well. They’re coming on the roads like gangbusters,” Washington Gov. Jay Inslee said. “It’s more difficult to electrify a plane. So we do what is easiest, cheapest and most effective first, which is electrify the ground transportation system.”

Inslee has made a name for himself on the national stage with his “climate hawk” positions. Yet he’s also a booster of the aviation industry, the sector that builds and operates little-regulated, heavily polluting flying machines.

Inslee’s proposed carbon tax, a pillar of his efforts to tackle climate change, would not apply to jet fuel. When asked why, Inslee told KUOW’s The Record, “We have to get the votes to pass the legislation to do this.”

Airplane maker Boeing has long been the state’s largest private employer, as well as a political powerhouse favored by Inslee with multibillion-dollar tax breaks.

“We pick our fights where there’s a snowball’s chance in hell of winning them,” climate activist Emily Johnston with 350Seattle said in an email when asked why environmentalists weren’t criticizing jet fuel’s exemption from the carbon tax.

In contrast to the special treatment for aviation fuel, gasoline and diesel would be taxed about 18 cents a gallon.

Even climate scientists struggle to reconcile the convenience and connection of flying with the harm it causes. “We travel a lot to conferences and advisory meetings for our work,” LuAnne Thompson, who directs the University of Washington’s climate change program, said of her fellow climate scientists. “Every time we step on an airplane, we know exactly how much carbon we’re burning, and yet we do it anyway.”

Thompson said she once asked to telecommute to a NASA meeting in Washington, D.C., and the organizers said yes. But she found teleconferencing in to the meeting “incredibly frustrating.” The experience left her convinced that current web technology remains a poor substitute for air travel.

“I think as climate scientists, we have to acknowledge that, even with really good web technology, it’s not going to be as good as face to face,” she said. “And that’s maybe a compromise we need to make.”