MOUNT VERNON — Inside an airy, stained glass-adorned room at Salem Lutheran Church, the Skagit Valley Chorale is surrounded by reminders of deep heartbreak.

Four doorways are propped open, two to the cool, outdoor air. A pair of homemade air cleaners, fashioned from furnace filters, a box fan and duct tape, hum away at the center of the room. A laptop streams video via Zoom. Two small monitors gauge the concentration of carbon dioxide — and alert the choir when too much of their own breath accumulates.

These are some of the safety measures the Chorale now takes after the coronavirus visited them in March 2020, when a seemingly ordinary choir practice became one of the country’s first superspreader events.

More than 50 members were infected, at least a handful hospitalized. Two died.

“We were burned,” member Leigh Giovane said Tuesday evening, before weekly rehearsal had started. The Chorale only recently returned to indoor activities. “Because we had such a devastating experience, we felt we had to be as careful as we could with the lives of our members.”

The group’s experience ventilating and filtering indoor air illustrates a new stage of the COVID-19 pandemic that Washington, along with much of the United States, is moving toward after the omicron variant infected vast swaths of the population.

State and local health officials say this transition will be a key period to prepare for future health crises. Vaccinations and boosters remain some of the best tools for protecting against severe disease and death, but as public health mandates — like for masking — have ended, experts say some long-term, structural changes will become even more important.

Improving indoor air quality is one of those changes. But steep barriers stand in the way, particularly for small businesses and schools, leaving many questions around what steps communities will take.

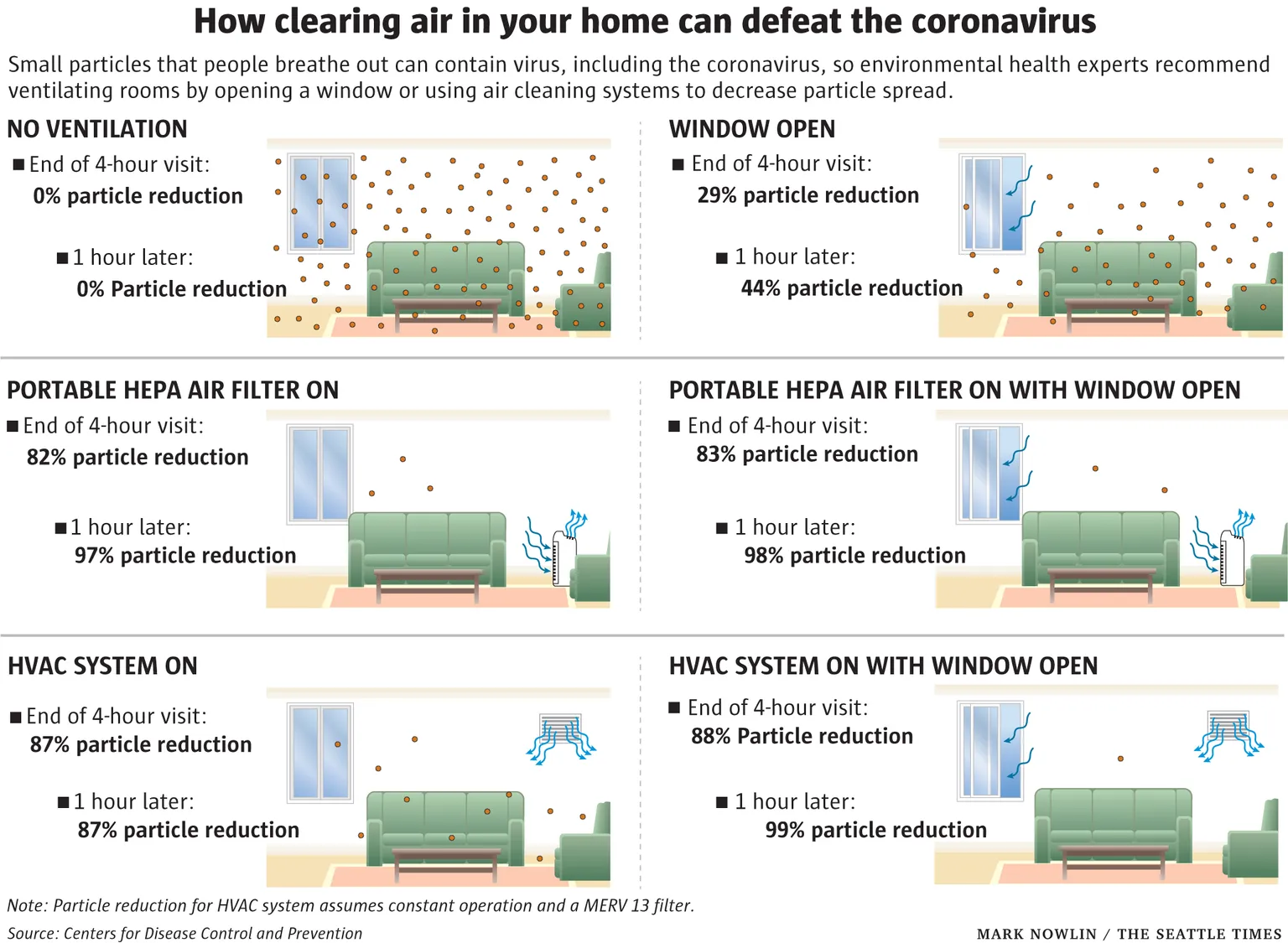

“Indoor air ventilation is extremely important to reduce transmission of the virus,” said Shirlee Tan, a toxicologist for environmental health services at Public Health — Seattle & King County. “There are easy ways to do that, whether you have an HVAC (Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning) system or not. Just opening a window or door and letting in some outdoor air can do a lot.”

In Washington state, some air quality standards, set by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, exist for different sectors, but there’s a huge need for new building codes and better statewide ventilation requirements, Tan said.

Studies show high-quality air ventilation systems help reduce transmission of airborne diseases, including COVID, by removing particles from indoor air. One study linked improved ventilation strategies in schools to a 48% lower rate of COVID.

Momentum appears to be shifting toward those efforts. The state Department of Health has committed to tackling the issue in its most recent pandemic plan by listing a number of recommendations, particularly for schools.

President Joe Biden this year also introduced a nationwide effort to improve ventilation in buildings, calling on schools and organizations to use federal relief — Washington received $1.8 billion — to adopt key strategies.

“Most of us spend 80% indoors, whether we’re at work or at home, so indoor air quality is really important for health and quality of life,” Tan added. “We’re hoping that becomes a sustainable message.”

Outreach and free filters

On a drizzly weekday in late March, Jenna Truong and Daniel Hwang, both part of King County’s environmental health team, spent the afternoon organizing and distributing free portable air cleaners to local business owners from a warehouse in Kent.

For much of last year, Truong and Hwang joined other public health staffers in reaching out to thousands of King County businesses, community organizations and school districts to explain the importance of better indoor air quality and set them up with portable air cleaners for their buildings.

The outreach is part of larger county efforts to teach community members about how good indoor ventilation can not only reduce COVID spread, but also increase long-term public health.

“COVID has changed a lot in the last two years, but the principles of good ventilation and how to improve indoor air quality have not changed,” said Marissa Baker, assistant professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington.

To date, Public Health — Seattle & King County has provided over 1,500 free evaluations of buildings and their air circulation systems and distributed nearly 2,000 HEPA filters — high-efficiency particulate air filters — to communities more at-risk of COVID spread. HEPA filters can remove 99% of dust, pollen, mold, bacteria and other airborne particles with a diameter as small as 0.3 microns, including particles that contain the coronavirus, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The efforts have helped many businesses facing challenges as they navigate often complex ventilation upgrades.

Outside the Kent warehouse, one local business leader, David Bestock, pulled his car into the parking lot to pick up an order of filters. Bestock, executive director of the Delridge Neighborhoods Development Association, arrived hoping to better clean the air at the organization’s Youngstown Cultural Arts Center.

“So, have you ever used one of these before?” Truong asked him, gesturing to a unit propped up on a table. After months of this work, she’s become an expert at giving a quick how-to on the machines.

In HEPA cleaners, indoor air passes through a series of filters that capture and remove pathogens before releasing clean air into a room. HVAC systems are bigger systems installed in buildings that often bring outdoor air inside, recirculate it and send it through a furnace filter before releasing it into a building.

“These filters are great year-round,” she said. “They help with wildfire smoke (and) they can help if anyone in your office has asthma or allergies, so they’re a really robust tool that isn’t just adding a layer of protection for COVID, but for other things as well.”

Bestock and his co-workers have secured a couple other HEPA cleaners as the Youngstown center slowly reopened to the public — but it’s an older building, meaning the options for good air filtration are limited, he said.

“We have HVAC units for two of our main rental spaces, but everything else is just windows and electric fans/heaters, which are on the ceiling and are terrible. … That’s why we need these,” he said.

Khadra Mohamed — who runs Saharle Daycare, a small, child care center in Kent — said she was hit with a huge wave of relief when she heard about the county’s efforts to give out the cleaners to local organizations.

“I went online weeks ago (looking for an appropriate air purifier) and it was $600,” Mohamed said after picking up two filter systems from the Kent warehouse. “I remember thinking to myself, ‘How am I going to afford this?’”

Several of her kids have bad allergies, she said, and while she tries to keep windows and doors open to bring fresh air inside, she needs a better system.