Sea-Tac Airport traffic is growing rapidly and set to expand further as the region’s economy booms. But in cities from Shoreline to Des Moines, airplane noise is raising increased concern among residents. Promised relief from a project called “Greener Skies over Seattle” never materialized.

After more than two decades living in Shoreline, retired attorney Jean Hilde says plane noise in the past three years has reached disturbing levels.

“I am one of those afflicted citizens, despite the fact that I live 25 miles from the airport,” she wrote to the Port of Seattle last year.

Hilde and other residents to the north could have been spared this affliction if an innovative air-navigation technology had been implemented, as proposed years ago, to guide inbound planes along a satellite-guided shortcut path over downtown Seattle.

However, that part of the plan called “Greener Skies Over Seattle” never happened, so neither did the touted cuts to noise, jet-fuel use and greenhouse-gas emissions over neighborhoods to the north.

Meanwhile, the region’s air-traffic growth has continued unabated.

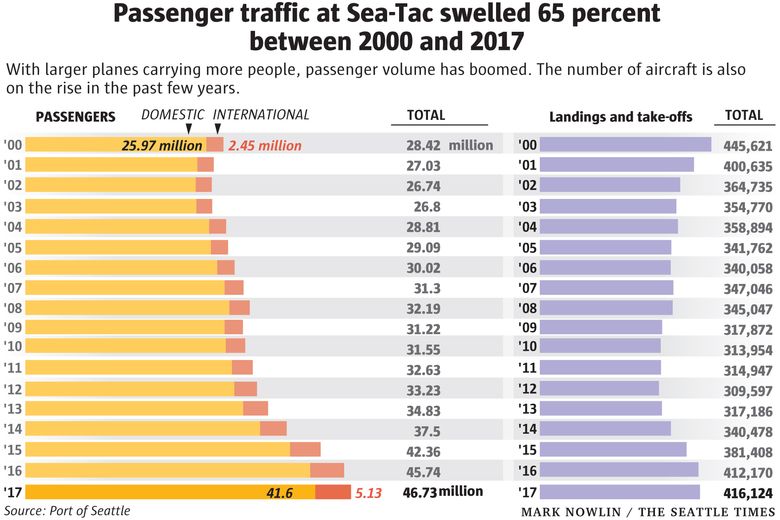

In the past five years, the number of aircraft flying into Seattle-Tacoma International Airport — one of the fastest growing in the U.S. — increased almost 30 percent and annual passenger traffic jumped from 35 million to 47 million people. Large airport facilities are under construction, and plans for further expansion, including a second passenger terminal, are taking shape.

Community activists are mobilizing to protest the impact on the ground. The Port of Seattle, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), airline representatives and local city officials are exploring potential noise-reduction measures — but none matches the scale of the massive projected jump in air traffic.

Frenetic growth

Surprisingly, fewer airplanes come in and out of Sea-Tac today than in 2000. The number dropped for some years last decade as airlines switched to bigger planes and packed in more people.

Since 2014, however, Delta has elevated Sea-Tac to a major hub and Alaska Airlines has matched its growth. In the past two years, seven international carriers flying widebody jets have added service to Seattle, with three more coming in 2019.

With that, the number of airplanes using the airport has climbed rapidly back up, so that the 416,000 landings and takeoffs last year are approaching the record level set in 2000.

And this month the FAA reduced the separation distances required between airplanes at Sea-Tac — allowing more planes in a given time span.

The Port is spending $3.2 billion on construction projects at the airport to meet existing demand, and proposes $4.5 billion in additional projects to meet anticipated growth through 2027.

Port Commission President Courtney Gregoire said the airport’s growth is “directly correlated” to the heated local economy, each driving the other.

The Port projects that Sea-Tac by 2027 will handle 56 million passengers and 480,000 landings and takeoffs. “The region is going to grow, whether we like it or not,” said airport director Lance Lyttle.

“Zippering” two streams of planes

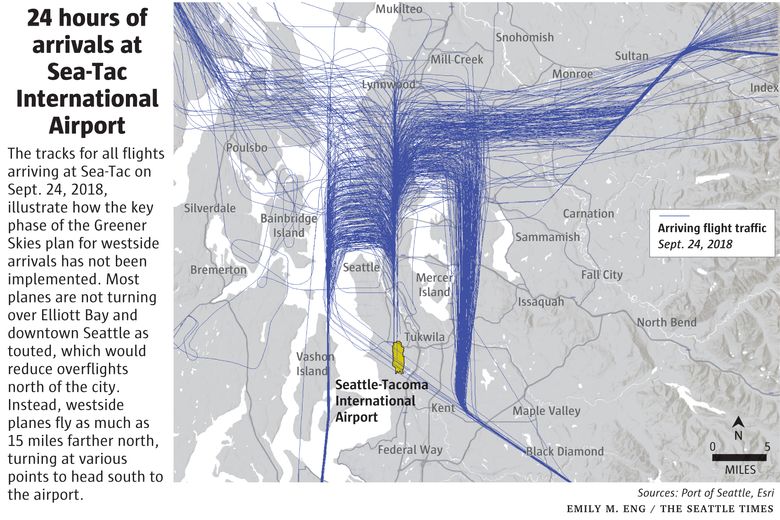

Neighborhoods far north of Seattle are affected by Sea-Tac traffic because airplanes typically land against the wind, which about 70 percent of the time blows from the south.

So all those planes arriving from south of Seattle — the majority — must fly north past the airport, overflying either Eastside cities or Puget Sound to the west, then turn southward in an arc for final approach.

As these planes come in alternately from east and west sides, air traffic controllers must “zipper” the two streams together, so that they merge onto a single south-flowing “glide slope” down to the airport, descending along a radar beam shooting out at a 3-degree angle from the runway.

The rosy forecasts of reduced jet noise in the northern suburbs promised by “Greener Skies Over Seattle” sprang from onboard technology that enables planes to follow a satellite-guided precision turn onto the glide slope. Alaska Airlines and Boeing did the careful work to develop such an automated flight path for the west-side planes.

The FAA heralded the project as part of its massive “Next Generation,” or NextGen, modernization of the nation’s air traffic system, projected to cost taxpayers $21 billion through 2030.

Instead, most of those planes could turn in a precisely guided arc over Elliott Bay and downtown Seattle, bringing relief to the residents of Shoreline and all points north of the Lake Washington Ship Canal.

This part of Greener Skies, which was first tested at Sea-Tac nearly a decade ago, was never implemented, however. A key reason is that no parallel satellite-guided path was developed for the east-side planes.

Air traffic controllers cannot safely merge two heavy streams of airplane traffic arriving simultaneously if one follows a precise automated path and the other is guided by conventional voice commands via radio. The software they use to predict where planes will join isn’t advanced enough to ensure safe separation.

“Due to the volume of arrival aircraft on both the east and west side, this is not feasible,” FAA spokesman Allen Kenitzer wrote in an email.

So the controllers do what they’ve always done. They guide both streams via voice commands.

If traffic is lighter, a plane can turn sooner. But at peak traffic every day, planes fly far to the north.

No precision track along the east side

Although the FAA says “we’re still working on that,” there is little prospect that the Greener Skies shortcut turns over Elliott Bay will happen in the foreseeable future.

In part, that’s because the planes arriving from the east are likely to remain conventionally guided for a long time. Unlike the west-side approach, which tracks north mostly over water — except for Vashon Island — planes on the east side fly over dense residential neighborhoods from Kent north to Redmond.

A satellite-guided track would be much narrower and concentrated than the current flight paths.

In an internal Port of Seattle email exchange in 2012, airport noise manager Stan Shepherd explained that an automated precision track on the east side “would definitely end up with condensing flight tracks over many residential communities.”

And that could invite lawsuits.

When NextGen changed the flight paths in Phoenix, Arizona, concentrating the traffic over a small number of residential neighborhoods without substantial consultation, the city sued in federal court, alleging that the FAA’s action was “arbitrary and capricious.”

A year ago, the U.S. Appeals Court ruled that the FAA had not sufficiently considered the impact of the changes, and ordered the agency to revert to the previous Phoenix flight paths.

[Related: Burien stirred up by roar from increase in Sea-Tac Airport overflights]

As part of its NextGen modernization, the FAA has authorized more than 390 of these precision-guided approaches nationwide. But the changes to established flight patterns and the concentration of traffic on narrow flight paths have raised vocal opposition in affected communities from Washington, D.C., to Santa Cruz, California.

So far, Phoenix is the only city to successfully roll back such flight-path changes.

A thin track over Vashon

While the turn over Elliott Bay hasn’t happened, one part of the Greener Skies plan farther out from Seattle was implemented: a new west-side flight path north from Olympia to Vashon Island.

Previously, air traffic controllers used the radio to guide pilots on this long approach. Individual planes tracked northward on paths spread out over a couple of miles laterally and descended in steps, leveling off for a time at each lower altitude step-down.

This is replaced with an automated, satellite-guided path that is more precise — narrowed to the wingspan of a jet — and descends in a smooth, continuous curve.

This curved descent avoids the repeated level-offs, which require a pilot to power up the engines. A plane can descend smoothly with the engines idle to Vashon, using less fuel and producing correspondingly lower carbon emissions.

To potentially hit that targeted early turn over Elliott Bay, the smooth descent was designed to drop lower than previous approaches.

Port data show that planes come over Vashon on a much narrower track and on average about 1,500 feet lower.

Port noise manager Shepherd said there’s been “an uptick in complaints from people that live directly under that condensed track” on Vashon.

Microsoft developer David Goebel bought a cabin on Vashon 20 years ago to get away from the bustle of Seattle. The quiet of his rural idyll is gone.

What gets to him, he said, “is the lack of a single 10 minutes’ peace in the day” from jets flying over. “I can’t even stand to be outside,” he said.

Once the planes pass Vashon, the continuous descent ends and planes begin flying level again.

The FAA’s latest available data for Sea-Tac Airport shows that during approaches between 2014 and 2017, the distance planes flew in level flight — with engines powered up, using more fuel and creating more noise — increased 40 percent, to an average 13.3 miles in 2017.

The increase cancels out at least part of any fuel and emissions savings from the continuous-descent path.

FAA spokesman Ian Gregor said the longer level-offs could be due to the heavier traffic, which rose 22 percent in that period, forcing more planes to fly farther north before turning.

Though Gregoire, the Port Commission president, said she hears complaints about plane overflights “every single day,” she emphasized in an interview that the FAA alone determines the flight paths, not the Port.

“I don’t get to set the policy,” she said.

The FAA responded to questions about noise impacts and Greener Skies via email. Gregor wrote that the agency “conducts appropriate environmental reviews” for all airspace projects.

Attempts to reduce noise

Earlier this year, the Port of Seattle formed a stakeholder advisory roundtable, including representatives of nearby cities, airlines and the FAA.

Airport director Lyttle said the group has identified four potential noise-reduction measures to study.

Two of these suggestions could decrease noise right next to the airport: not using the runway closest to the airport boundary when traffic is less busy, and asking pilots to curtail noisy reverse engine thrusts on landing.

Another possibility is raising the glide slope slightly for planes landing from the south. And another being looked at is negotiating a voluntary night curfew, something that legally cannot be imposed on the airlines.

“There are limitations to what we can do,” Lyttle said.

The Port’s projections for Sea-Tac go out to 2034, when it anticipates annual traffic reaching 66 million passengers and 540,000 landings and takeoffs.

A lengthy environmental-review process that kicked off last month as part of the Port’s Sustainable Airport Master Plan, covering expansion through 2027, will include public hearings in about a year.

Sheila Brush, a Des Moines representative in the stakeholder meetings who leads an airport activist group, Quiet Skies Puget Sound, is cynical about the process. She says the Port is “just checking the boxes.”

This story was updated at 3:45 on October 25 to say that airplanes at Sea-Tac typically land against the wind. A previous version said they must land against the wind.