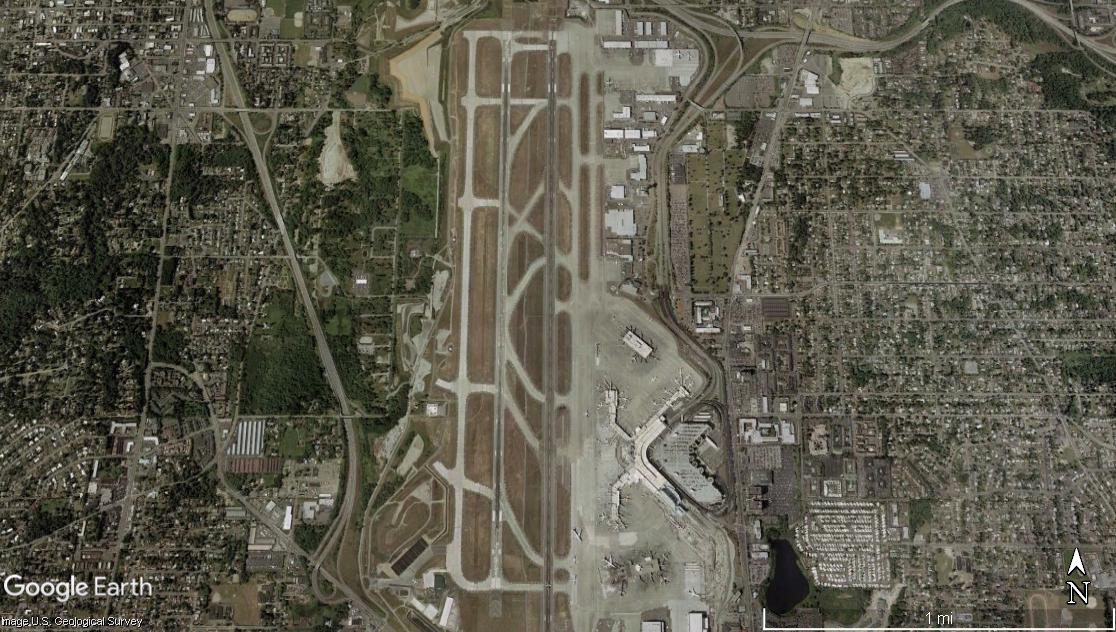

In 1996, the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) gave final approval to the Port of Seattle’s proposal to build a Third Runway.

The airport was originally sited on a small plateau about 430 feet above sea level, which ended immediately at the west side of what is now Taxiway Tango. The basic struggle in airport expansion at Sea-Tac has always been as much about land as air. So, every time the airport has wanted to expand it’s meant an incursion into the surrounding neighborhoods.

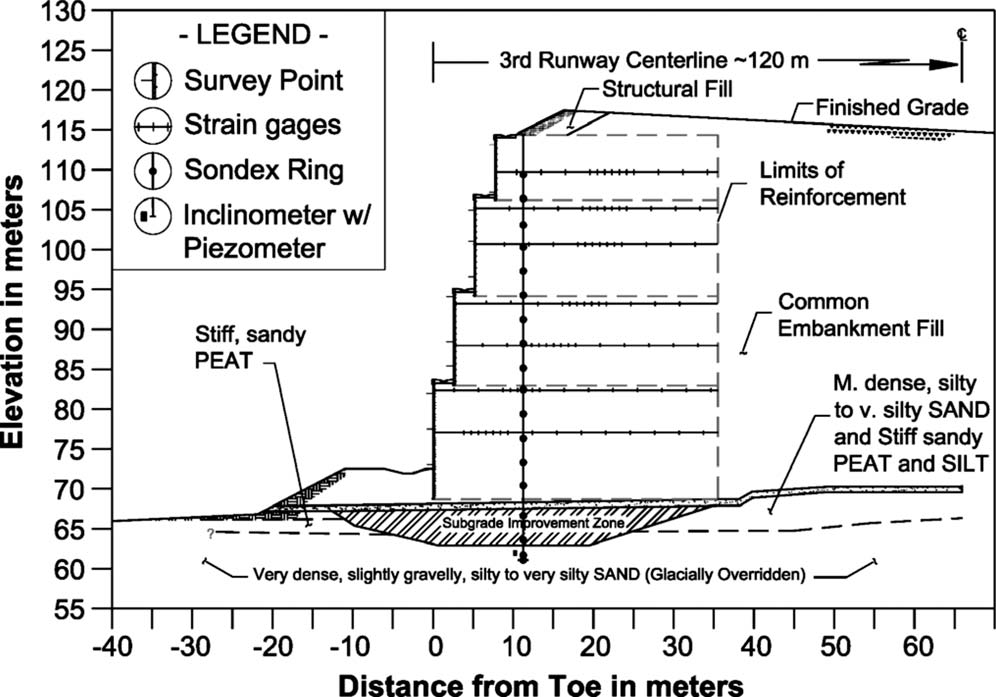

Apart from the usual engineering challenges of laying a super-flat, super strong piece of asphalt known as a commercial runway, 34L/16R presented a series of unique engineering challenges. We’ll get to all those pesky environmental challenges and property buyouts elsewhere, but it’s worth taking a minute to mention the engineering because although the techniques utilized were not exactly new, they had not been applied on a project quite this large and mission-critical.

Speed

Once the Port got past all those pesky lawsuits, it actually took less than two years to erect The Great Wall. In fact, it took less time to build the Third Runway than to resurface the Second and First runways later.

Part of that speed came from staging and strategic planning. The Port had been preparing every aspect of the process ahead. For example, prior to 2000, about 50% of operations were general aviation and commercial taxis and were generally handled on a subsidiary runway never used by commercial carriers.

By 2007, that ratio had shifted to about 3% and that stretch of asphalt, now known as Taxiway Tango was ready to go.

And then there was Port Spokesman Bob Parker’s famous quote:

“I’m told, by people who know, that you can’t wait for all your permits to begin work. If you did, you’d never get anything done.“

Which was a nice way of talking about all the trucks that had been delivering fill dirt to the site all the while the Port was defending multiple lawsuits. The mood among residents in Burien and Des Moines was a mixture of black humor and resignation.

Dirt

Speaking of dirt, the Great Wall Of Sea-Tac required a lot. Seventeen million cubic yards to be precise. To get that much fill dirt to the site took 500,000 dump truck loads, running 20 hours a day down SR-509 onto a custom-built exit ramp which was simply abandoned after work was complete.

At the time, ‘global warming’ was on just about no one’s mind, so the environmental threat was considered to be the dirt itself.

A gallery of The Great Wall

To give readers a sense of the engineering, here is a timeline of pictures of the western side of the airport property. One can see that the taxiway to the west of the Second Runway almost marks the extent of the plateau.

Don’t call it a wall

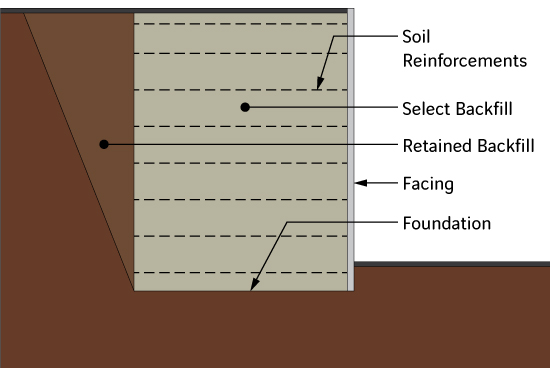

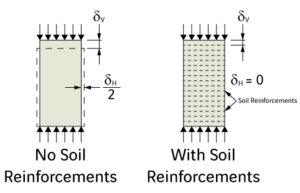

The Great Wall is constructed using a system called mechanically stabilized earth (MSE). And the people who sell MSE systems like to say that they aren’t actually selling ‘walls’. Because the part you can see isn’t actually holding back anything like a retaining wIfall. An MSE is constructed with an alternating series of materials that are constantly pushing against one another. The theory of MSE’s is that in case of an earthquake, the shaking actually makes the structure more stable.

The Great Wall is constructed using a system called mechanically stabilized earth (MSE). And the people who sell MSE systems like to say that they aren’t actually selling ‘walls’. Because the part you can see isn’t actually holding back anything like a retaining wIfall. An MSE is constructed with an alternating series of materials that are constantly pushing against one another. The theory of MSE’s is that in case of an earthquake, the shaking actually makes the structure more stable.

When it works, it is the most stable system in the world. But the trick is this: to get the balance just right.

Saggy

Apart from the… er… ‘not a wall’, an ongoing concern is actually subsidence on the runway itself. The Third Runway is not a part of the original plateau. It was built partly over wetlands and next to Miller Creek. So again, setting aside all that pesky flora and fauna, this tends to make creating a surface that will remain stable over a long period of time, difficult. It’s not like a road or a bridge where one can simply drive piles deep enough to support structural members. The challenge is to make sure that the entire field doesn’t get ‘saggy’ after a few years.

The MSE is designed to provide proper drainage

Looming

It’s kinda tough to get up close now, but another feature of the walls are that they not perfectly vertical. They lean inward very slightly. This is also not structural., it’s to make the front appear vertical. Massive objects that are perfectly square appear to lean towards the viewer; not something you want from something this massive when you’re trying not to make the neighbors nervous.

Monitoring

You’ll be glad to know that the Great Wall is not set it and forget it. There is a series of monitors which measure that incline and the ongoing forces pressing against the MSE. So, unlike many roads and bridges which require manual inspections to indicate structural problems, the Great Wall is designed to alert engineers of problems before they get out of hand.

Still not level…

The funny thing is… it’s still not level. With all that effort building the Great Wall of Sea-Tac, the Third Runway is ten feet lower than the Second Runway. The center runway is higher than either the Third or the First runways and the entire airfield slopes from about 430 ft. above sea level at the north end down to 363 ft at the south end.

Before shrugging that off as an unimportant detail that only an airport nerd would care about, we’ll keep saying it: when it comes to the airline business and the FAA there are no unimportant details–especially when you spend $1.1 billion dollars on something that was supposed to cost $200 million.

The elevation, length and separation of each of these runways will return in this story over and over as Sea-Tac planners worked to squeeze every operation they could out of “largest small airport in America.”