Gov. Jay Inslee, right, speaks with Greg Crider, an air monitoring scientist with the Department of Ecology, as he visits the Jefferson Park-Beacon Hill Air Monitoring Station in Seattle on Tuesday. (Karen Ducey / The Seattle Times)

Half a dozen areas around Puget Sound, and even more across the rest of Washington, will soon see a new piece of technology to confirm what many residents already know: that they suffer from rampant pollution.

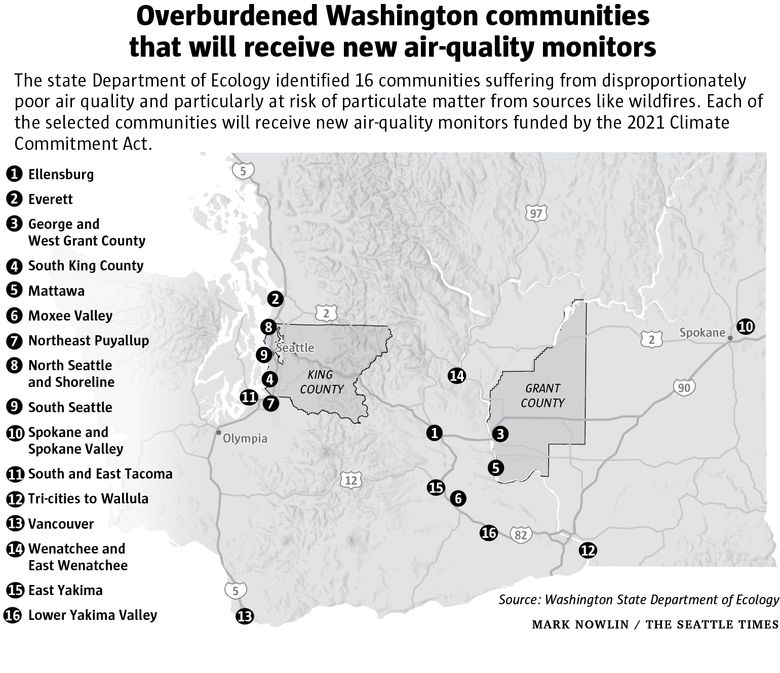

Washington’s Department of Ecology announced Tuesday it will install 50 new air-quality monitors in 16 communities with poor air quality and a vulnerable population.

But some environmental justice advocates say the new monitors aren’t enough and that a higher proportion of money collected from the state’s carbon-pricing auctions, which are funding the new air monitors, should be spent on communities most vulnerable to climate change.

State officials should follow through with actions to cleanse the air of pollution, said Esther Min, director of environmental health research for the nonprofit Front and Centered Washington.

“Science is only useful if you make use of the data,” Min said.

A recent analysis from the nonprofit indicates that money from the 2021 Climate Commitment Act, which puts a price on greenhouse gases emitted in the state, isn’t going toward overburdened communities as much as politicians had promised.

State officials say the new monitors are an important step in learning where air pollution, specifically particulate matter from sources like wildfires and wood-burning stoves, hits the worst and directing their resources accordingly.

“This is a targeting device,” Gov. Jay Inslee said Tuesday. “We have a great instrument to generate weapons in the war against pollution.”

Inslee and other state officials also underscored their commitment to protecting overburdened communities with the state’s climate funds.

New air-monitoring devices

Watch out for errant golf balls, Inslee warned Tuesday afternoon as he toured the Jefferson Park-Beacon Hill Air Monitoring Station. The governor, recovering from a recent bout of COVID-19, spoke through a black face mask and tipped his head to the driving range directly east.

The air-quality station has been running for decades, said Jill Schulte, Ecology’s statewide ambient air monitoring coordinator, but the governor was on-site to examine five new additions hanging on a bit of chain-link fence.

The sensors, called SensWA, are small, less than a cubic foot, with a clear plastic front. They’re inexpensive and so lightweight that they can hang almost anywhere, Schulte said. And they’re specifically designed to measure levels of PM2.5 in the air.

PM2.5 stands for particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers, which can be inhaled and cause or exacerbate respiratory and cardiovascular issues. Common sources of this type of pollution include wildfire smoke, wood-burning stoves and vehicle emissions.

Twenty of the SensWA sensors are now working across the state. Aside from those in Beacon Hill, more are operating in places like Issaquah, Spokane, Vancouver and Cle Elum, Kittitas County, said Susan Woodward, a spokesperson for Ecology.

The department will add dozens more to areas near Ellensburg, Everett, Puyallup, the Tri-Cities and Wenatchee, Woodward said. Each of those areas, 16 in all, qualify as overburdened, meaning they experience greater risk from the air pollution than most other communities. Combined, those 16 communities include more than 1.2 million people.

Tribal communities won’t be covered by the new monitors, but Woodward said state officials are consulting with tribes and expect to include them in the future.

Min applauded the new monitors but questioned the state’s next steps to clear pollution. She also noted the devices only detect particulate matter and not other chemicals and compounds known to plague overburdened communities.

But Inslee said the added information can be used to direct additional funding raised from the state’s carbon-pricing auctions, which have collected nearly $1.5 billion in less than a year. That money could help residents afford heat pumps, more-efficient insulation in their homes, air filters and electric vehicles. Each of those investments would improve air quality, he said.

Over the next two years the Legislature has allocated more than $2 billion from the funds for those types of projects.

Still, Min said, some places are falling through the cracks.

Where Climate Commitment Act money is spent

It’s likely that more communities than the 16 highlighted by the state are overburdened by air pollution, Min said. But they probably didn’t make the list because they don’t have enough air quality data to qualify, she said.

Woodward said state officials believe it’s “unlikely” they missed areas with both vulnerable residents and high levels of air pollution. Ecology will continue to gather data and speak with community members and tribes, and the department will revise its list every six years.

That’s too long of a wait, Min cautioned, especially because an analysis published last month by Front and Centered indicates the state isn’t directing enough money from the Climate Commitment Act to overburdened communities.

The Legislature required that at least 35% of the money raised by the policy be spent in ways providing “direct and meaningful benefits to vulnerable populations within the boundaries of overburdened communities.” In addition, 10% of the total expenditures must go toward tribal communities.

But the budget falls well short, the analysis indicates.

So far, up to 10.6% is allocated to overburdened communities and 6.2% is allocated to tribal communities, the nonprofit’s data shows.

Becky Kelly, senior policy adviser for climate in the governor’s office, disagreed with the analysis and said it was too simplistic in counting what does and does not qualify as spending in an overburdened community, Kelly said.

“We do the math really differently,” Kelly said.

Guillermo Rogel, legislative and government relations advocate for Front and Centered, noted that state officials don’t have any hard data to dispute the analysis, though.

“There is no math yet, we haven’t seen it,” Rogel said.

Either way, little of the money raised so far has been spent. Inslee acknowledged the spending commitments to overburdened and tribal communities and said his administration will abide by them. He also said that spending more of that money will not only help reduce pollution but will also build support for the Climate Commitment Act itself, protecting the policy against a growing repeal effort.